Passchendaele: The village that gave its men to war

- Published

Volunteer soldiers from Brimington pictured in 1914 - at least two were killed at Passchendaele

Brimington, near Chesterfield in north-east Derbyshire, sent hundreds of its men to fight in World War One. Fifteen of them were killed at Passchendaele. Now, a couple from the village have traced out the lives, and graves, of those who died on the battlefield 100 years ago.

Charles Hurst and Fred Hobson were friends, bound together by their lives in Brimington, a busy working-class village where they lived during the early 1900s.

They worked in the same production shop for the Staveley Coal and Iron Company, and played cricket together.

Most notably of all, both stepped forward on the same day in March 1917 to enlist, and fight for their country.

After basic training, they both joined The Queen's Own Royal West Kent Regiment on 20 July, just before the Battle of Passchendaele.

That battle began on 31 July 1917, and is one of the most-remembered battles of World War One.

An estimated 320,000 men were killed and wounded on the Allied side, and the conditions were nightmarish. Some parts of the muddy battlefield were so deep that men drowned.

Fred, 23, got married five days before signing up. We don't know if Charles, 22, was there, or if he was Fred's best man, but it seems possible.

What we do know is that these two young friends, who worked, played sport and went to war together, died together at Passchendaele on 12 October, and that their bodies have never been found.

There are no photographs of them, but their names are engraved on the Tyne Cot Memorial in Belgium.

Sally Mullins used the Brimington war memorial plaque as the foundation of her research

We only know all this today because of Sally and Stuart Mullins, a couple from Brimington who have spent years bringing to life those men who sacrificed theirs.

"Stuart had an uncle who died in World War One, and another in World War Two," says Sally.

"In 1998 I got hold of an aged computer and started tinkering around on the internet, looking for information on his relatives. Then I just began looking into soldiers from Brimington."

Sally, 64, says she and Stuart, 70, have worked as a team on their relentless research. Stuart describes his wife as "research", and himself as "logistics".

Brimington's memorial is on ornamental gates - the land behind was once a sports field

Sally's starting point was the village's war memorial, containing 120 names. She says the number of those killed is actually higher, but for various reasons some were not included on the memorial. Many more men were left maimed by the fighting.

Using the plaque's names as a base, Sally traced the soldiers's histories, using military records online. Her task was not made easier by some vague names, such as F Brown. And to complicate matters, some names were misspelled. Charles's surname of "Hurst", for example, is recorded as "Hirst".

She also spent hours at Chesterfield library, squinting at microfiche replicas of local newspapers, booking the one computer attached to a printer and "spending a fortune" on printing out military records, and newspaper pages containing notices of a soldier's death on a battlefield.

The Mullins also bought, at some cost, the entire 1901 census.

Tyne Cot in Belgium is one of the places overseas where Brimington's men are commemorated

At least 800 of Brimington's young men went to fight in World War One, and among the many stories Sally has unearthed is one involving four brothers from the village.

Private George Bradshaw, 27, joined the Sherwood Foresters in 1915 and saw action in the Balkans and France before his battalion was moved to the Ypres area in 1917.

He was awarded the Military Medal for bravery on 16 August 1917 but was killed at Passchendaele on 19 October, leaving behind a wife and young son.

He is buried in Tyne Cot Cemetery in Belgium, but his headstone only became engraved with "MM", to mark his medal, after the Mullins spotted that it was missing and reported it.

George's brother John was shot in the ankle in 1915 and died in the Battle of Arras in April 1917, while another sibling, Thomas, died in Belgium in October 1914.

Just one brother, Len, who served in India and France with the Yorks and Lancs regiment, survived the war. There is no record of the boys' mother in the local archives, or of how she coped with such a terrible loss to her family.

Queen Street remains largely unchanged since 1917 and is where Charles Hurst lived

An honorary mention must be given to one of Brimington's residents, Fred Greaves, who won a Victoria Cross for his bravery at Passchendaele. Although born elsewhere in Derbyshire, he loved living in the village and remained there after the war until his death in 1973.

What's also come to light is how the young men of the village at the start of the 20th Century, who worked in mines and did back-breaking factory work, were clearly as fit as a fiddle.

"Our local schoolboys' football trophy was the Clayton Challenge Shield - it was the prestigious competition of that era," says Sally. "By 1913 Brimington boys had won the shield four times in eight years.

"Unfortunately by the summer of 1917 and Passchendaele, at least seven players of the old Brimington teams were already dead, killed in action in earlier arenas of the Great War."

Years later, armed with an updated computer, Sally has now painstakingly pieced together enough information to run a Brimington history website, external and self-publish a memorial book of all the village men lost to the war.

She coos and rubs her palm lovingly over the page of one soldier as she talks about him.

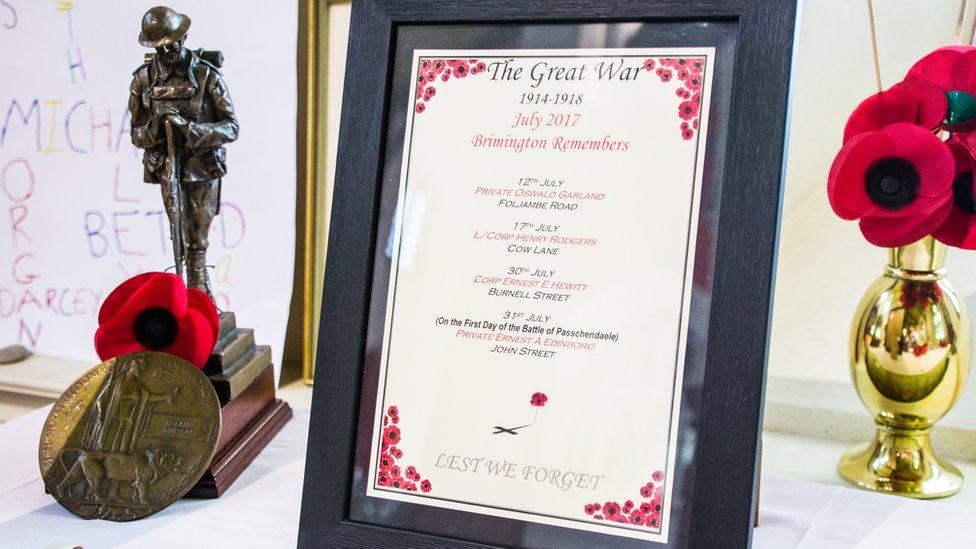

Since August 2014 she has been printing out a list of the soldiers who died in the corresponding month 100 years ago, during World War One. This goes on display on an altar at one of Brimington's churches, where it is read out by the rector at the start of each month.

The list of fallen soldiers is displayed in St Michael and All Angels Church in Brimington

Not only have the Mullins made a huge effort to remember Brimington's boys on paper, they have travelled extensively around Belgium and northern France to find their graves.

Sally and Stuart, who are attending the 100-year commemorations being held at Passchendaele, have been making about four visits a year to the region. They started in 2004, driving themselves around with maps and their own, Brimington-inspired itinerary. Once, they covered a 1,000-square-mile area in a week.

They seek out the well-known cemeteries containing thousands of soldiers, as well as tiny plots with a few dozen bodies laid to rest, ones not usually found on battlefield tours. It's in all these places that they find the men from their village.

Stuart says upon reaching the grave of any of "our lads", the couple feel "heartbreak" and sometimes become tearful. He also says they follow the same ritual each time.

Stuart reaches out his hand to demonstrate and speaks with a Derbyshire accent, warm and comforting.

"We always pat the headstone and say 'We're here, lad. We're here.'"

- Published25 July 2017

- Published21 July 2017

- Published25 July 2017