Grenfell: Can public inquiries ever satisfy everyone?

- Published

The public inquiry into the Grenfell fire disaster is beginning its formal work.

But there have already been weeks of passionate debate about what it should cover and who should run it.

Why does such passion surround what looks, on the surface, like a dry official procedure?

That is partly because of dispute and uncertainty about what a public inquiry does.

Firstly, it is not a court of law and it is meant to be independent.

However the government decides whether to hold an inquiry in the first place, appoints its head, and has to agree what it is going to cover.

Inquiries can then make recommendations about how things should change but governments do not have to accept them.

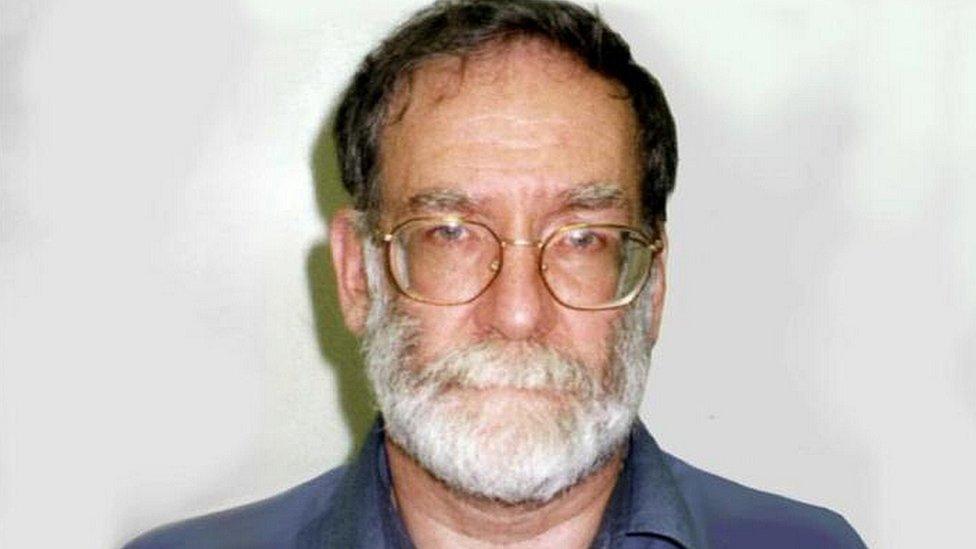

The Shipman inquiry produced far-reaching recommendations

And the history of public inquiries tells us something more.

They are about people, not just procedure, so they reveal all kinds of conflicts in our fast-changing society over things like government secrecy, deference, and the power of professions.

Dame Janet Smith - a High Court judge - chaired the inquiry into the GP and serial killer Harold Shipman.

She told me what happened just after she was appointed and was told her terms of reference.

That is the procedure - which has just been agreed for the Grenfell inquiry - which sets out what an inquiry is going to cover.

The government wanted her to focus on organisational failures that had allowed Shipman to act undetected.

But his trial had only covered a fraction of his crimes.

Dame Janet sensed that the families of Shipman's victims wanted most to find out what had happened to their dead relatives.

Find out more

Chris Bowlby presented Archive on 4: Inquiries - Facing Our Failures on BBC Radio 4 on Saturday 19 August at 20:00 BST.

Or you can listen online via the BBC Radio 4 website

"They were very anxious that I should investigate who Shipman had actually killed," she said.

"The government did not want me to do that. They only wanted me to look at the systems that had failed."

So after the Lord Chancellor had dictated the terms of reference to her, she decided she needed to re-jig it a bit.

"I put in a section that was capable of being extended… but didn't explicitly say so," Dame Janet said.

She later told the Lord Chancellor that she wanted to investigate all the deaths.

"I said my terms of reference do seem to make that a possibility," she told me.

Dame Janet Smith wanted to cover more in the inquiry

"They were so anxious to get an inquiry underway I think they would have agreed to more or less anything."

There were highly emotional moments in the Shipman inquiry as tragic individual stories were told.

"There were occasions when I had to put my head down because I was having difficulty controlling my face," Dame Janet admitted.

"But the formality of the occasion helps you and them get over it."

She knew her approach was going to double the cost and the length of time for the inquiry, "but it was the right thing to do".

So how effective was her inquiry overall?

Dame Janet made several clear recommendations for change in public policy covering areas such as death certificates and drugs monitoring.

But then politics came back into play and the government had to decide how far it would respond.

Ministers came and went, and three different departments were involved.

"It was hopeless, like herding cats," Dame Janet recalled.

Limited implementation of her recommendations after so much work was "a great disappointment".

A healing process?

Victims and their families have played a growing role in public inquiries.

Some see inquiries becoming more like the truth and reconciliation commission seen in South Africa after apartheid, allowing voices to be heard, and stories to be told in an official setting.

Sir Paul Jenkins, who was the Treasury Solicitor, the government's top legal official, between 2006 and 2014, said he had experienced in inquiries a sense of "a healing process, giving the victims giving the survivors a voice so they can be heard, listened to, understood".

Politicians, he believes, can see value in this as a safety valve when feelings are running high.

By contrast, when an inquiry is seen to have ignored those most affected, it can fuel a politically powerful sense of injustice.

The Saville inquiry into Bloody Sunday - the killing in 1972 of 13 civilians by the army in Londonderry - was the second inquiry into that event.

The first, by the Lord Chief Justice, Lord Widgery, soon after the event, was widely seen as a whitewash.

Saville, said Sir Paul, "had to deal with the legacy of the bad inquiry so if he had been anything other than obsessed with the detail… it wouldn't have been of any value at all."

"It was bound to take a very long time," he added.

Sir Martin Moore-Bick has already faced calls for his resignation from the Grenfell inquiry

"The good legacy," he explained, "is it led to David Cameron standing up and saying sorry - when something has gone wrong and the state is at fault that is how inquiries should end up."

"The bad thing is - [now] in ministers' minds all inquiries take 12 years and cost £200m."

Worries about cost and length are part of a growing frustration within government about public inquiries.

Politicians take the initiative in setting them up, and decide how far to implement their recommendations.

But the independent way in which they are conducted makes politicians nervous.

A new law on inquiries in 2005 gave governments more powers to restrict what inquiries can do.

Dame Janet Smith said that when she pointed out to civil servants that the law's provisions allowed a government department to interfere in an inquiry, they replied: "Oh we don't think we'll ever need to use them."

"They wanted to get a little bit more control," she argues.

"But they shouldn't have control - the inquiry should be wholly independent of government."

The Grenfell inquiry is likely to be prolonged, emotional and constantly in dispute.

It will be a major challenge for it to match, in its investigation and reporting, the depth of anger about what happened in that terrible fire.

And it will be the next chapter in the turbulent history of how Britain has inquired into many of its worst moments, exposing a society and its underlying tensions as it works out why things sometimes go so wrong.

- Published15 August 2017

- Published15 August 2017

- Published29 June 2017

- Published28 June 2017

- Published23 June 2017