London fire: Inquest versus inquiry

- Published

At least 79 people are now missing, presumed dead, following the fire in west London

Following the tragedy at Grenfell Tower there have been calls for both an inquest and a public inquiry.

The prime minister has announced that there will be a public inquiry, but how will that differ from an inquest?

More importantly, which will provide the best chance of delivering answers to the critical and haunting questions of what caused the fire, and which organisations or individuals bear responsibility?

Inquest

An inquest is an independent inquiry into a violent or unexplained death, so as a matter of course, there will be inquests into those who lost their lives in Grenfell Tower.

Inquests are held in public and conducted by a coroner.

The coronial system can be traced back to the 11th century. The inquest is inquisitorial and not adversarial - that is, the process does not seek to determine or apportion responsibility for the death. Its remit is limited: it solely determines who, where and how the deceased died.

But inquests can be expanded if Article 2 of the European Convention on Human Rights - the right to life - is invoked.

There is a general duty on the part of the state to protect life, and Article 2 inquests are held where the state or a public body may have played a part in the death of a person, or failed to protect a life when it knew - or ought to have known - of a real and immediate risk to the life of that person.

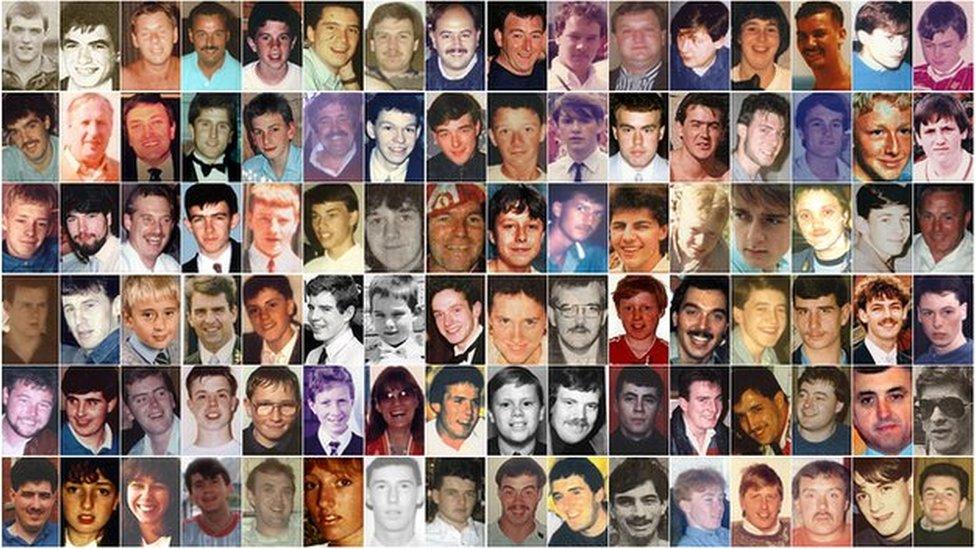

The Hillsborough inquests found that all 96 Liverpool fans had been unlawfully killed in 1989

Such inquests will generally be conducted with a jury, and can be greatly expanded to become wider reaching inquiries into not only by what means the deceased died, but also the circumstances surrounding the death.

This can cover the involvement of a range of private and public organisations. The recent inquest into the death of 96 football fans at Hillsborough in 1989 was an example of this expanded "Article 2" type of inquest.

The coroner can make what are known as Regulation 28 recommendations to prevent future deaths. This involves writing to individuals, bodies or organisations and advising what they need to do to prevent future deaths or guard against danger to the public.

However, these recommendations have no legal force. The person, body or organisation in question may face overwhelming moral pressure to comply, but would not be under a legal duty to do so.

Sometimes the bodies or organisations concerned will already have reviewed or changed systems or practices in advance of the inquest. If they have not and they do not comply with the recommendations, it is then down to government to legislate to change the law to prevent or guard against further loss of life.

Judge Frances Kirkham made clear recommendations after the 2009 Lakanal House fire

The lack of legal force behind coroners' recommendations was seen after the inquests in 2013 into the death of three adults and three children who died in a fire at the Lakanal House flats in Camberwell, south-east London.

The coroner, Judge Frances Kirkham, made clear recommendations, external, which included updating the building regulations and clarification of the "stay put" policy which advises residents to remain in their flats in the event of a fire. Those recommendations were not followed by ministers.

What does have legal force is the inquest's determination as to the cause of death, commonly known as the "verdict". The verdicts available to a coroner or a jury are prescribed by statute. These include suicide, accident, open verdict and unlawful killing.

Where there is a jury inquest, the coroner will advise the jury as to what verdicts are available to them.

The legal consequences of a verdict can be seen for example in unlawful killing. Here there is a presumption - though not an absolute obligation - that the Crown Prosecution Service (CPS) will take action against those responsible.

The CPS is currently considering criminal charges against a range of people and organisations following the finding last year that 96 fans were unlawfully killed at the Hillsborough disaster in 1989.

Public Inquiry

Public inquiries are designed to establish what happened, learn from events, prevent any recurrence, and reassure. Unlike inquests they do hold people to account.

However, public inquiries are set up by the government. It appoints the chair who is normally a senior judge.

The Grenfell Tower inquiry is likely to be established under the Inquiries Act, which means the chair will have statutory powers to summon witnesses, compel them to give evidence on oath and produce evidence.

That can strengthen the power of an inquiry over an inquest. Counsel to the inquiry can put detailed questions to witnesses, both on behalf of the inquiry itself and at the request of key interested parties.

Relatives of the Bloody Sunday victims react to the Saville Report, which stated that all victims were innocent

Some take the view that because the government establishes the public inquiry, holds its purse strings and sets its terms of reference, it can lack independence.

Public inquires have also been criticised for the time they take and the cost to the public purse. The "Bloody Sunday" inquiry into the deaths of 13 people during the troubles in Northern Ireland took 12 years and cost around £200m - though some estimates put the figure far higher.

However, there are many examples of robust, independent public inquires that have been conducted efficiently.

The "Mid Staffs" inquiry into the scandal of poor care at Mid Staffordshire NHS Foundation Trust conducted by Robert Francis QC, which was run on a punishing timetable and made a raft of important recommendations taken on board by government, is often held up as an example of how a public inquiry should be run.

Robert Francis QC was widely praised for the way he ran the Mid Staffs public inquiry

However, it should be noted that like a coroner's recommendations, those of a public inquiry have no legal force.

The Mid Staffs example also illustrates the critical importance of selecting the right person to chair the inquiry.

That person sets the tone and needs the right mix of high level interpersonal skills to communicate with the families of victims and win their trust, the intellectual ability to master technical evidence and regulations (this will cover complex construction issues and building regulations in the case of Grenfell Tower), and the personality to drive the inquiry legal teams effectively and efficiently.

Which works best for victims and their families?

Both can work well.

Hillsborough is an example of a long and painstaking inquest that addressed the needs of victims' families.

Robert Francis QC met relatives of patients who were mistreated at Stafford Hospital

The Mid Staffs public inquiry was an example of a successful inquiry that did the same.

There are however issues around the representation of victims and their families.

At inquiries, victims and their families are given the status of "core participants", and it is up to the chair to ensure that they are given legal advice and representation that puts them on an equal footing with well-funded private and public bodies. The money for that representation comes direct from government and legal aid does not apply.

At inquests, publicly-funded legal representation is not automatic. However, following a tragedy on the scale of Grenfell Tower, it would in all likelihood be provided. Whether this would ensure "equality of arms" with other bodies involved in inquests, is open to question.

In the Queen's speech, the government announced plans to introduce an independent public advocate for all public disasters, who would act on behalf of bereaved families and also support them at public inquests.

There is no detail on quite how the public advocate will operate, but it would seem that the role is one of supporting families rather than representing them at inquests,

Inquests, inquiries and criminal proceedings

Inquests will generally not be held or completed until all criminal investigations and prosecutions have taken place.

Public inquiries can take place alongside criminal investigations, but must be respectful of them and not prejudice their outcome.

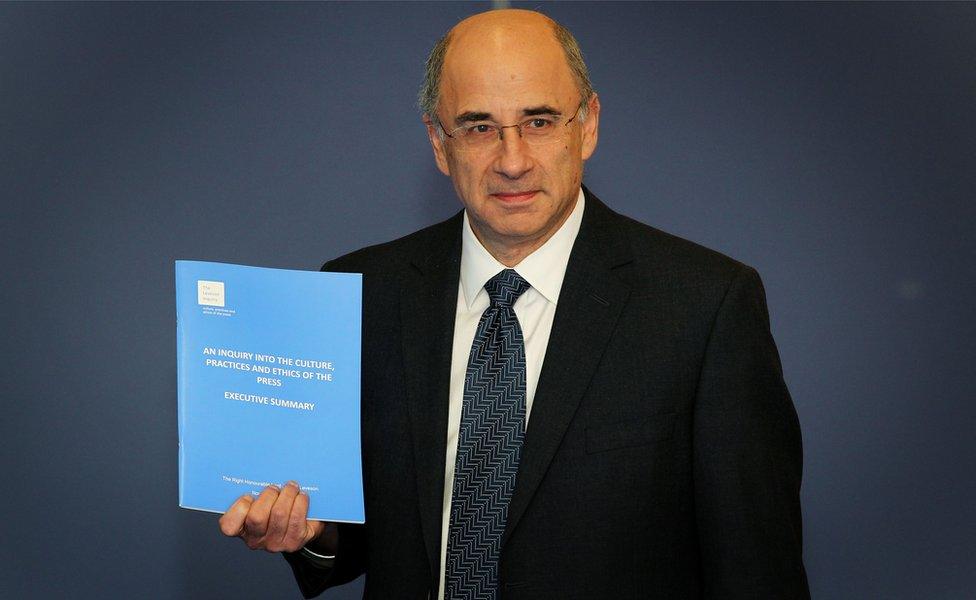

Lord Justice Leveson had to conduct his inquiry at the same time as criminal proceedings

This was seen in the Leveson Inquiry into press standards which had to tread carefully around concurrent criminal prosecutions.

Some will favour an inquest, others a public inquiry.

The truth is that both, if well run, well funded and with powerful recommendations that are acted upon by government, can be highly effective ways of progressing justice and ensuring that similar avoidable tragedies never happen again.

- Published18 May 2018

- Published14 June 2017

- Published16 June 2017

- Published16 June 2017