Grenfell: Test results show scale of building regulations problem

- Published

New cladding tests have shown not only that there are widespread problems with materials used in buildings, but also within institutions that we charge with keeping us safe. The government has announced a review of building regulations. To be successful, it will need to take on a sector that struggles with respecting its own rules.

The last significant results of a set of large-scale fire tests were released today. They imply that 228 buildings have cladding that may require replacement or modification.

You would be forgiven for having lost the thread of how we got here. But the rough story so far goes like this: after Grenfell, the government effectively commissioned an audit of buildings across England to establish what type of aluminium cladding was used on which buildings. They also audited the types of insulation that lay underneath them.

They found three broad types of aluminium cladding in use based on how well they could resist fire:

First, so-called "PE" cladding. This is the type used at Grenfell: its name comes from the fact that it has a polyethylene (plastic) core. This is the least fire-resistant type of panelling.

Second, so-called "FR" (fire resistant) cladding, which is a bit better in a fire.

Third, so-called "A2" cladding, which has a mineral core of limited combustibility.

Armed with that information, the government commissioned six large-scale tests which sought to establish which types of insulation could safely be used with each of these cladding types. These fire tests are rather large enterprises: they mock up large-scale models of different wall systems using different combinations of insulation and cladding. They then light a fire under them to watch what happens.

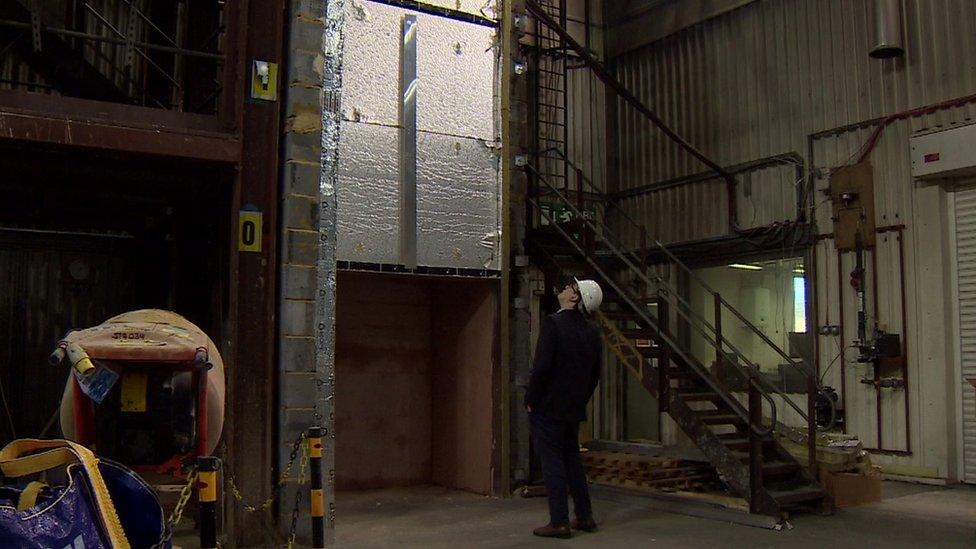

Fire test rig used at the BRE, with reporter for scale. The empty cavity at the bottom is where the fire is placed.

The government commissioned two tests for each aluminium cladding type: one with a traditional mineral wool insulation, which is basically fire-proof. And one with a combustible insulation - a so-called "PIR" foam, which is the type of insulation used at Grenfell.

Such tests are really supposed to happen before designs using combustible materials are installed on buildings (we have written rather a lot about why this process did not happen previously - but we will return to some of those issues).

The full-scale tests

The results came in as follows: "FR" cladding passed when paired with non-combustible insulation, external. Plastic combustible insulation passed when it had the protection of the most fire-proof aluminium panels, external. But otherwise, all, external the, external tests, external failed.

One of the original six tests is still outstanding, but it is almost certain to pass.

However, the government has commissioned a seventh test. The rationale for it is that not all plastic foams are alike. The original tests used so-called PIR foam insulation. But there is another popular type of combustible plastic foam, known as "phenolic" foam, which is held to have quite different fire performance.

The test rig at the BRE before the alumnium cladding was installed for the first test using PIR insulation and PE cladding. This shows the interior design of the cladding. The silver foil covers the insulation. The vertical yellow stripes are firebreaks intended to stop the fire moving horizontally. The black stripes are firebreaks designed to stop vertical fire spread

It was conceivable that a phenolic could pass the test with FR-grade cladding, even if PIR did not. So that was the seventh test - the test for which we got the results today. The phenolic did, indeed, perform a little better than the PIR - but it still failed. The phenolic was deemed to have failed the test after 28 minutes. The equivalent PIR test lasted just 25 minutes.

Kingspan, a manufacturer of phenolic insulation, said that they intended to commission "further tests of phenolic insulation in combination with a range of FR and non-combustible" alumnium panels in order to improve the evidence base available. They expected that phenolics would pass the test when mounted under non-combustible panels, just as PIR foams had.

Altogether, that test means the government knows of 228 buildings with cladding that is of a configuration which failed the test. The lesson appears to be: if you must use combustible insulation, box it in with panels of limited combustibility. And if you really want to use FR cladding, you need to pair it with fireproof insulation.

But there is a bigger result to these tests.

The failure of the institutions

The tests reveal the failure of some of the institutions we have charged with making sure that building standards are maintained.

A principle of our building regulations is that if you wish to use combustible materials on the exterior of tall buildings, the design of cladding system you are using should be subject to a fire test. Sector bodies did not uphold that principle.

Soon after the Grenfell fire, Newsnight revealed how one of the entities that signs off buildings, supplying so-called "Approved Inspectors" to developers, had issued worrisome advice. Not just any body, either. The National House Building Council (NHBC), the very first entity outside local government to be given the authority to do building sign-off back in the 1980s.

They announced last September that they would sign off a variety of combustible insulation boards combined with cladding with a combustible core - and they stated that you did not need to do a test nor commission a study to use such combinations. NHBC themselves stated that "this is on the basis of... having reviewed a significant quantity of data".

Some of these combinations have now been explicitly shown to be unsafe. Newsnight's reporting led them to withdraw their advice at the time, back in June, but their judgments about building safety must be called into question. On what basis did they introduce this sweeping guidance?

Friends and relatives of victims of the Grenfell Tower fire joined local residents for a silent march to mark the second month since the disaster

Exova Warringtonfire, one of the few longstanding fire engineering companies, also has questions to answer.

They wrote reports which implied that phenolic insulation could be used safely with FR-grade aluminium panels. They stated that you could use combustible insulation and combustible cladding. And this was not on the basis of conducting actual fire tests on the designs in question.

Instead, Exova argued that the aluminium panels would behave, in a fire, in a similar way to ceramic tiles. Thus, fire tests using ceramics could be used as a substitute for systems using aluminium cladding. When we first published this story, sector experts were shocked by Exova's judgment - which we now know to be flawed.

We have asked both Exova Warringtonfire and the NHBC for comment on the evening of this publication - although the late hour of publication has made it difficult for them to respond.

NHBC tonight simply stated that they will only sign off buildings using a reading of the rules that take "the results of these tests into account". Exova said their studies "are based on the data available at the time and issued on the understanding that they are subject to review if further data becomes available".

The principles in our building regulations could be better drafted. But the bigger problem appears to be that institutions we expected to care about fire safety did not uphold the standards we demanded of them.