What do the latest migration figures reveal?

- Published

There are so many important headlines in the August migration data that it is difficult to know where to begin.

Let's start with the biggie - is there a Brexit effect that is frightening workers off from the British economy?

Anecdotally, many of us who report on this field have picked up these stories. I spoke to a lot of Eastern European workers around the time of the general election who were rather nervous but somewhat resigned to Brexit. But not many of them suggested to me they were going to get on the first budget flight back home.

But today's data gives us a really good glimpse into the thousands of individual decisions that ordinary people make about their future.

Net migration - that's the difference between the number of immigrants coming in for a year or more and the number of people who emigrate - has fallen substantially since the referendum. In March 2016, weeks out from the vote, it stood at almost 330,000.

Today it is 81,000 down at 246,000 people - the lowest it has been for three years.

The estimates from the Office for National Statistics, external show that two-thirds of this fall in net migration is accounted for by changes in EU migration, and particularly by citizens of Eastern and Central Europe.

In the year to the end of March, fewer EU nationals arrived to live in the UK than in the previous 12 months - and there was an acceleration in the numbers leaving.

When you look at the figures for the 10 nations of Eastern and Central Europe, we can see that 62,000 of their citizens said "do widzenia" ("goodbye") to the UK while 26,000 fewer of them arrived.

When you drill down further, net migration from the A8 nations (Poland and others which joined the EU in 2004) has dropped very sharply. In the year to March 2016, 39,000 more of these citizens arrived than left. In the year to March 2017, that had crashed to just 7,000.

Interestingly, notes Prof Jonathan Portes of King's College London, these figures show, for the first time, a stabilising of arrivals from the eight Eastern European nations - and that suggests they no longer regard the UK as as attractive as it once was.

"Net migration from the A8 countries, which joined the EU in 2004, is now statistically insignificant for the first time since then," he says.

"Moreover, figures for National Insurance registrations, which measure new arrivals registering to work, also fell, with the number of EU nationals registering in April to June falling more than 12% on the same period a year earlier.

"These statistics confirm that Brexit is having a significant impact on migration flows, even before we have left the EU or any changes are made to law or policy."

Falling pound

For its part, the ONS is cautioning that it's too early to say this is a long-term trend. So are there other factors beyond a suspected Brexit effect?

Since the Brexit referendum, the falls in the pound on currency markets mean that money made in the UK buys less back home.

This is really important for workers who are sending cash back to their families - and a decisive factor in decisions to move all around the world.

Last June, the pound bought almost 6 Polish zlotys. Today, it buys only 4.6 zlotys.

What's more, when people choose to move to another country, they're not just looking at the circumstances there, but, fairly obviously, at the conditions at home.

And there is no doubt that for some EU workers, coming to the UK isn't the slam-dunk deal it once was.

The Polish economy, for example, has one of the strongest growth rates in the EU and its government is lobbying workers to stay at home, rather than take their skills elsewhere.

Whatever the precise factors, the government will want to present all this as a victory for its strategy and progress towards its net migration target.

And while campaigners for falls will be buoyed by the statistics - some are urging caution.

"This is a step forward but it is largely good fortune," says Lord Green, chairman of Migrationwatch UK, a pressure group.

"It is mainly due to a reduction in the huge net inflow of East Europeans from 100,000 to 50,000. This should not obscure the fact that migration remains at an unacceptable level of a quarter of a million a year with massive implications for the scale and nature of our society."

That's a pointer to the scale of the challenge ministers still face, if they are determined to stick to their target. Net migration from the rest of the world still stands at 180,000 people a year - and that is the one part of policy that the UK can currently completely control.

Exit checks

The August figures have also revealed some fascinating truths about migration, and people's intentions, that until now have been subjected to myth, fears and an awful lot of speculation - do people leave the UK when they should?

Well, we don't really know - or at least we didn't until now. The ONS uses a large rolling survey at ports to estimate immigration and emigration - but it's only as good as a survey can be - it has limitations.

Now, we have "exit checks" data - figures derived from the scans of passports and so on as people leave the UK at our ports.

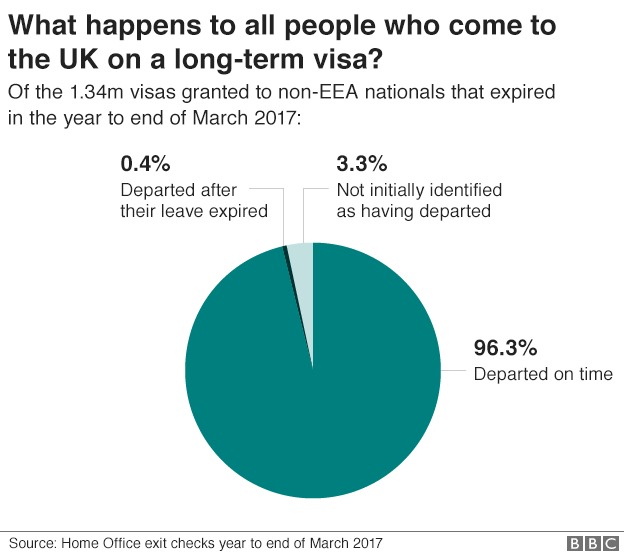

And the figures from the Home Office show, for the first time, that the vast majority of visitors to the UK who require a visa leave the UK when they should.

Exit check data indicates that 97.4% of international students comply with their visa requirements

Some 1.34 million visas granted to non-EEA nationals expired in 2016-17. Of those people who had not already secured a legal reason to stay on, 96.3% departed in time. A further 0.4% left after their visa expired. It's not quite clear what happened to the remaining 3.3%.

So, of all those visas, around 40,000 overstayed.

And what's even more interesting are the figures around students. International students have been a hot topic in the migration debate with some claiming that they habitually overstay their visas. Some of the predictions for student over-stayers have been enormous.

The exit check data shows the rate of compliance - those who play by the rules - was 97.4%. And that suggests that assumptions about mass overstaying are either simply wrong or, alternatively, a thing of the past after a crackdown on bogus colleges.

- Published24 August 2017

- Published24 August 2017