How legal drafting may be central to fire safety debate

- Published

One of the emerging themes in the post-Grenfell investigations into fire safety across England is that policy on fire safety is something of a mess. Standards have not been upheld by the sector. But it is important to note that the government has questions to answer, too.

There have been questions asked about why they failed to respond to concerns raised by the reports into the 2009 Lakanal House fire already. But something that I expect to emerge in the coming inquiries is that the building regulations are, at best, ambiguous about fire safety when it comes to what we expect of so-called "rain-screen" cladding.

That is the type used at Grenfell Tower, where you have a layer of insulation pinned to the exterior wall of the building. It gets its name from the fact that you then place a weather-proof layer, such as a layer of aluminium panels, over the top of it to shield it from the elements.

The specific issue in question is whether the fire safety rules that apply to the insulation should also apply to that exterior layer of aluminium cladding. The section of the regulations relating to fire - "Approved Document B" - contradicts itself about what it takes for a cladding system to meet the fire safety guidelines.

This is a bit involved, so apologies for getting into the weeds.

The cover of Approved Document B

The prescriptive route

One of the routes to complying with the fire safety requirements was the so-called "prescriptive" or "linear" route. That means: following one set of specific conditions set out in the regulations to the letter. (There are other routes which we have covered elsewhere.) So what does the document actually say?

Let us start with paragraph 12.5. That states: "The external envelope of a building should not provide a medium for fire spread". The document then goes into more detail. Paragraph 12.7 adds: "In a building with a storey 18m or more above ground level with insulation product, filler material... etc. used in the external wall construction should be of limited combustibility".

That term - "limited combustibility" - has a precise meaning. It means that the material must have been shown to be fire-proof, in effect, in a sequence of tests. It should, in the jargon, be of class "A2".

If you just took those portions of the document alone, I think it would be clear that everything - both cladding and insulation - must be A2 or better. The document does not specify that the external cladding must be limited combustibility, but the meaning would be clear enough.

How else could you be sure that the "external envelope of a building should not provide a medium for fire spread"?

That reading was presumably the intent of the drafters. It is how the government reads it. The Building Control Alliance, a sector body, issued advice in 2014 stating that "all elements of the cladding system" on tall buildings should meet that requirement. The Buildings Research Establishment reads it this way. We have sought legal advice which also supported this position. So while we have previously reported on the issues around this, we have tended to take this line as the legal baseline.

Contradictions in the rulebook

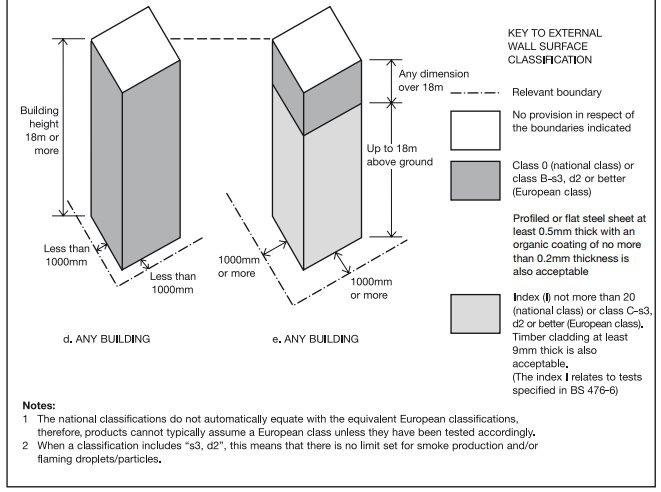

But other parts of Approved Document B introduce ambiguities. For example, you can browse slightly further down in the document to Diagram 40, where the document contains this image, which shows the requirements on buildings of more than 18m.

It shows that the outer surface of buildings above 18m must be either "Class 0" or "Class B-s3, d2 or better".

Excerpt from Approved Document B, Figure 40

What does that mean? Well, those are fire safety categories which are below class A2. Class B is one notch down from A2. That is peculiar.

If all parts of the cladding are supposed to be of A2 grade, why does this imply that the exterior panels need only be B-grade? There are other issues too, and they add up to mean you can mount a case that the document should be read to imply that the insulation must be of limited combustibility, but not the exterior skin.

For example, remember that paragraph which mentions "limited combustibility"? It mentions insulation by name and is headed with the words "Insulation products/materials". But it does not mention the exterior panelling. However, Diagram 40 clearly does. Surely, if the exterior had to be of grade A2, Diagram 40 would make that clear?

What counts as filler?

When we have asked people in the sector who support the official position about this, they said: go back to that paragraph 12.7. Remember, that says: "In a building with a storey 18m or more above ground level with insulation product, filler material... etc. used in the external wall construction should be of limited combustibility".

Yes, it does not mention cladding, but their view was that the "etc" in that sentence must cover the cladding. Yes, the paragraph is headed "Insulation products/materials", but surely the aluminium panels solely designed to protect insulation foam from the elements are an insulation product?

And how else do you make sure that the "external envelope of a building should not provide a medium for fire spread"? In this reading of the rules, Diagram 40 is just superfluous.

The government seems to be making a slightly different argument. The cladding, remember, is made of thin sheets of aluminium pressed around a core made of something else. That core, the government argues, should be counted as a "filler" for the purposes of this document. So it is not caught by the "etc" in paragraph 12.7, but is included as "filler material".

A local resident holds a piece of scorched material from Grenfell Tower at a meeting of Kensington and Chelsea council

They have recently started taking to referring to the interior of the panels, the stuff that they used to called "the core", as "filler". There's a problem, here, though. Builders have insisted to us that, in the context, of insulation and cladding, the word "filler" has a very specific meaning. It is the foam you used to pack voids - not the inner core of an aluminium panel.

You might ask: why does this matter?

The first reason is that when the government tested non-combustible B-grade panels with a polyethylene core, they found they were very combustible, even when paired with non-combustible insulation.

If the government's reading of the rules is not supported in court, it would mean it would be possible to mount that unsafe combination on tall buildings within the letter of these "linear" rules. (Not the combination used at Grenfell, though - there is no doubt that insulation must be non-combustible when following this route to compliance.)

Second, it helps explain why, even if the BCA, government and BRE thought that the rules should be read in one way, others could disagree. There are 124 buildings known to the government which have a combination of non-combustible insulation with some type of B-grade aluminium panelling on the exterior.

The final reason is legal: when it comes to working out who pays for what, the fact that the DCLG has produced a document which is ambiguous makes it more likely that the taxpayer will end up paying more to resolve this mess.