Should sexual harassment be a criminal offence?

- Published

It started with Harvey Weinstein, one of the biggest names in cinema, then went global with the #metoo Twitter hashtag before engulfing the UK's members of Parliament.

The sex scandal spanning Hollywood, Parliament and beyond has exposed a possible gap in UK legislation - sexual harassment is not actually a criminal offence in its own right.

The Equality Act currently covers sexual harassment in the workplace - but outside work, prosecutors must use different pieces of legislation, depending on the nature of the offence.

Critics say this leaves us without a proper definition of the types of behaviour that amount to sexual harassment - or clear boundaries.

It also makes it near impossible to get an accurate picture of the scale of the problem.

So, is it time to make sexual harassment a specific criminal offence?

Should Parliament decide where the bar on acceptable behaviour falls?

"Of course sexual harassment should be criminalised," says Samantha Rennie, director of Rosa, a charity which supports initiatives for women and children.

Two-thirds of UK women have reportedly been sexually harassed so it's important that we have the law behind women, she says.

But Conservative MP Maria Miller, who chairs the Commons Women and Equalities Committee, has her doubts.

"It's a really difficult area. It's not an easy area of law," she says.

Society and Parliament would have to decide where the bar falls - what behaviours were acceptable and not acceptable, she explains.

Most parliamentarians and police would consider sexual harassment outside work "too big and too difficult an issue" to treat with the same zero-tolerance approach that we do, for example, race hate crimes, she says.

"That in itself is very telling - we have got a huge cultural problem here, and it needs to be tackled."

Sophie Walker, leader of the Women's Equality Party, is not convinced a "quick change in the law" would resolve low conviction rates around sexual harassment.

"People are rightly looking for a silver bullet," she says - but she believes that a fundamental change in the balance of power in everything from work and caring, to representation and rights is what is needed.

Is sexual harassment of a woman a hate crime?

BBC reporter Sarah Teale was harassed by a passerby during her report on a conference about harassment

No - not in most places.

In England, Wales and Northern Ireland, hate crimes fall into five categories - disability, race, religion, transgender identity and sexual orientation.

However police forces can create their own categories, depending on local concerns and problems.

Nottinghamshire has done just that - recording harassment as a misogynistic incident - and other areas are starting to follow suit.

Ms Miller says if this was taken up by other forces, it would be a straightforward way to record incidents and get an idea of the scale of sexual harassment.

Samantha Rennie says hate crimes are prosecuted when race, sexuality and other prejudices are apparent, so gender should be no different.

When has a law change like this worked?

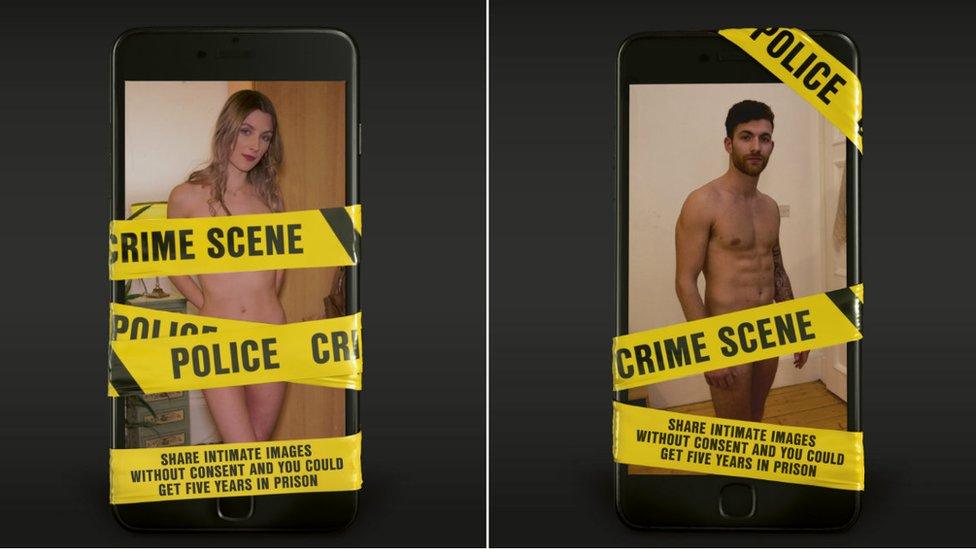

Posters in a hard-hitting campaign in Scotland earlier this year highlight the new "revenge porn" law

Revenge pornography is one example.

Until 2015, there was no specific law against the offence, which often involves an ex-partner uploading sexual images of someone to humiliate and embarrass them.

Instead, convictions were sought under existing copyright or harassment laws.

Within a year of the Criminal Justice and Courts Act 2015, external coming into force, 206 people in England and Wales had been prosecuted for disclosing private sexual images.

Lead campaigner Maria Miller cited figures suggesting that before the law was changed only two prosecutions had been made.

In Scotland, cases are brought under the Abusive Behaviour and Sexual Harm Act 2016., external

If not a new law, how does current legislation stand up?

The Equality Act - which covers sexual harassment at work - needs more teeth, Ms Miller says

The Equality Act 2010, external - which offers protection at work - sets out a clear framework and covers what is most people's experience of sexual harassment, says Ms Miller.

It includes sexual jokes on email, hugging and staring in a sexually suggestive way.

However, she says the legislation leaves the victim to do "all the running".

They have to highlight the Equality Act to their manager and, if that doesn't help, take their case to a tribunal.

A claim must be brought within three months of the alleged act of harassment and a claim can be made simultaneously against the employer and the perpetrator.

Ms Miller believes the government should look at giving the Equality Act, which covers England, Wales and Scotland, more "teeth" by making elements statutory as with, for example, maternity rights.

Sexual harassment in the workplace can damage self-confidence and career prospects, she says: "It feels an important area to get right."

Sian Hawkins, from Women's Aid - a charity which supports abused women - says existing legislation needs to be regularly reviewed to make sure allegations are dealt with properly, victims get the right response and perpetrators are held accountable.

"The criminal justice system needs to send a clear message to everyone that sexual harassment is unacceptable and that this crime is taken seriously," she adds.

How many people have been prosecuted for sexual harassment?

We don't know.

Perpetrators can currently be tried under a number of different pieces of legislation.

For example, a man sending a woman unwanted messages could be charged under the Protection from Harassment Act 1997, external, and fondling on public transport would come under the Sexual Offences Act., external

Because it's not necessarily recorded as a sexually-motivated offence, the Crown Prosecution Service is unable to get a true figure.

In the workplace, more than half of women said they had been sexually harassed, a TUC survey from last year found. However only a fifth of them told their employer.

The reasons they gave for keeping quiet were fears for their careers prospects and working relationships, concern they would not be believed and embarrassment.

- Published1 November 2017

- Published19 October 2017

- Published6 October 2017