How UK-Zimbabwe relations went sour

- Published

Tony Blair pulled out of talks to fund Robert Mugabe's controversial land reforms in 1997

Britain's relationship with Zimbabwe has always been complex.

A former imperial power can feel torn between a responsibility towards its ex-colony and a reluctance to interfere in what is now an independent state. And a freshly minted nation can feel resentment towards its former ruler while also hoping to maintain longstanding trade and cultural links.

Thus it has been for London and Harare.

Take, for example, President Mugabe. For years, he has railed against Britain and its political leaders as they opposed his disastrous land reforms, his persecution of white farmers and his calamitous management of Zimbabwe's economy.

But Mr Mugabe is also an Anglophile who loves cricket, the Royal Family and Savile Row suits.

He developed a surprising friendship with Lord Soames, the last British governor of what was then Rhodesia, whose son, Nicholas, the Conservative MP, he saw only a few weeks ago.

And when Mr Mugabe's cabinet colleagues were celebrating the fall of Margaret Thatcher in 1990, he rebuked them, reportedly saying: "Who organised our independence? Let me tell you - if it hadn't been for Mrs Thatcher none of you would be here today. I'm sorry she's gone."

Zimbabwe began life as a colony of the British South African Company in the late 19th Century, run by the British empire-builder, Cecil Rhodes.

The moment Zimbabwean MPs hear Mugabe has resigned - BBC News

In the 1920s, Southern Rhodesia, as it was then known, was annexed by the United Kingdom but with an element of self-government. The white minority ruled for decades, but were increasingly challenged by nationalist campaigners.

Eventually, in 1965, the government led by Ian Smith unilaterally declared independence from Britain. UDI, as it was known, prompted international outrage and sanctions.

Years of guerrilla warfare in the bush led to pressure for a negotiated settlement in Rhodesia, and, in 1979, Britain hosted all-party talks at Lancaster House in London. And from this process emerged a peace agreement, a new constitution and a former guerrilla fighter and leader called Robert Mugabe - the first prime minister of a newly independent Zimbabwe.

Robert Mugabe has said he trusted Margaret Thatcher - in contrast to Tony Blair

Even then, Britain's relations with Mr Mugabe were ambiguous.

Politicians and diplomats at the time placed a huge amount of faith in him as exactly the kind of strong, pro-western leader that Zimbabwe would need to embed its new-found independence and democracy. But he nevertheless was still able to wind them up.

Lord Carrington, Britain's foreign secretary who chaired the Lancaster House talks, described him as "devious and clever, he was the archetypal cold fish". On a dull moment in the talks, Lord Carrington rejoiced with glee when he discovered that Mugabe reads backwards as "E ba gum".

Lord Hurd, another British foreign secretary, told The Africa Report that: "Mugabe was one of those people the British Empire created who specialised in knowing how to twist the British government's tail. He was well-trained in the art of annoying the British if he needed to. He knew our ways."

Hotel protests

At first, Britain was hopeful about Zimbabwe's prospects. And normal relations were maintained.

The Princess of Wales visited Mr Mugabe in Harare in 1993. The England cricket team, led by Michael Atherton, played Zimbabwe in Harare in 1996.

But over the decades of Mr Mugabe's rule, as the country slipped into greater autocracy and economic decline, relations deteriorated.

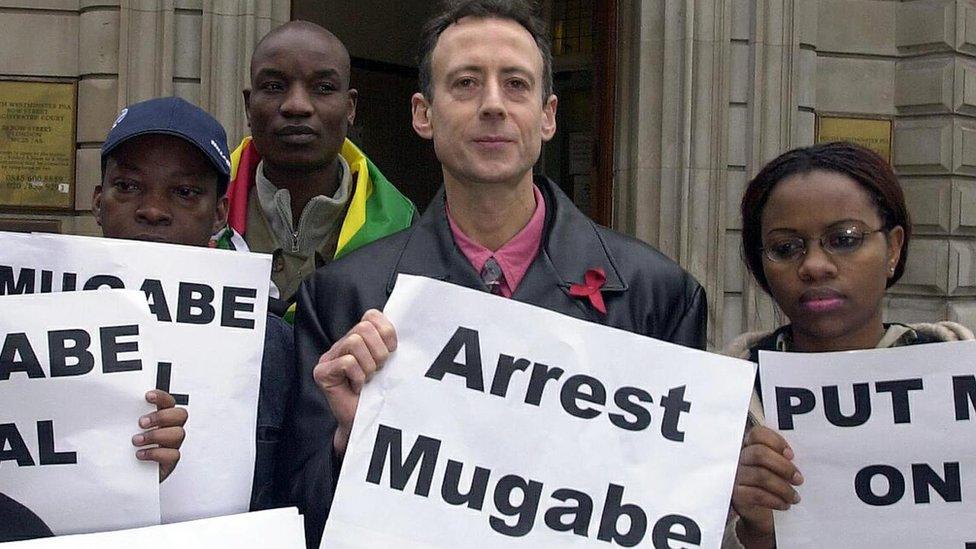

Campaigner Peter Tatchell protested regularly in London against Robert Mugabe

In 1997, Tony Blair's government pulled out of talks to fund Mr Mugabe's controversial land reforms. The Zimbabwean president accused the British of meddling in his country's affairs by funding his political opponents.

Britain began to withdraw development aid and sanctions were imposed on the president and his inner circle.

Campaigners such as Peter Tatchell would protest regularly against Mr Mugabe's homophobia outside the hotel in St James' where the president stayed on his frequent visits to London.

Yet through all this, Mr Mugabe still hoped Britain might help revive his country's ailing economy. As he told a crowd a few years ago when he was celebrating his 90th birthday: "The British, we don't hate you, we only love our country better."