The early Christmas gift many of us now buy

- Published

Marks and Spencer had a waiting list of more than 45,000 online customers for its 2017 calendar

Advent calendars used to be a cheap way to count down to Christmas with a seasonal picture or chocolate treat, but behind the doors you can now find everything from expensive whisky to fancy face cream. Are they a rip-off that represents the ever-growing commercialism of Christmas, or just a harmless bit of festive fun?

"Christmas isn't like it used to be," is a familiar refrain. Yet even putting the rose-tinted spectacles aside, one element of the festive period - advent calendars - really have come a long way.

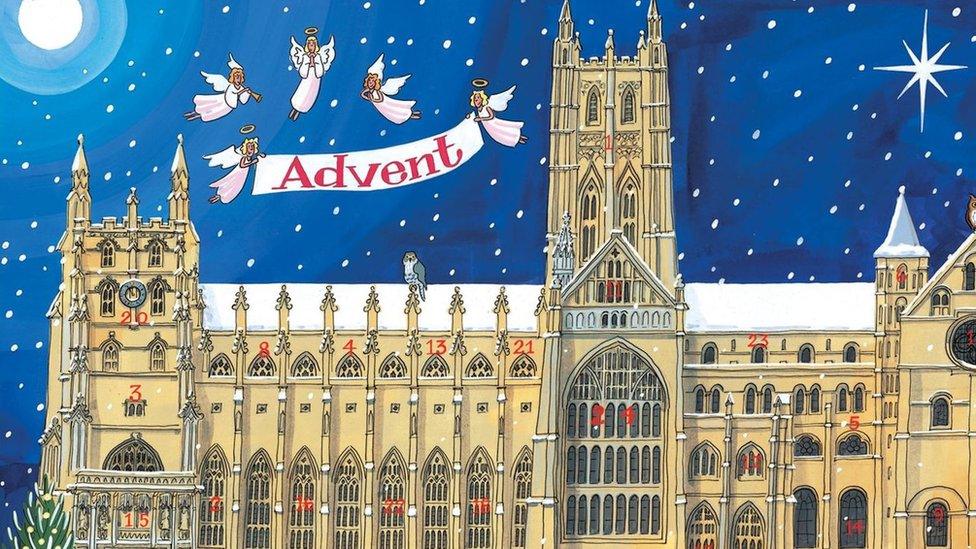

There has long been a tradition in some Christian denominations to mark off the days of Advent, from lighting candles to the calendar's austere origins in 19th Century Germany, external when 24 chalk lines were rubbed off doors.

But counting down to a festival marking the birth of Jesus has changed, from finding cheap chocolate behind the door of a pretty picture - a style popularised in the 1990s - to an extravagant present-filled bonanza boasting everything from pork scratchings to posh toiletries.

Traditional card advent calendars are still popular, says John Lewis

These bumper versions vary wildly in price, ranging from £10,000 for a rare whisky version, to a rather more modest cheese offering for £8 from Asda.

But despite the sometimes eye-watering cost, some do represent value for money, according to MoneySavingExpert's Gary Caffell.

"If you want to give yourself a small daily treat of your favourite tipple, cheese or crisp, Advent calendars such as these are meant to be a bit of festive fun. So if that's why you're buying it and you're happy with the overall price, you may not be too fussed about the value you're getting behind each window."

"Self-rewarding" is how consumer psychologist Kate Nightingale, founder of consultancy Style Psychology puts it.

When you are rushing around trying to please everyone else, treating yourself to an early present is one way to cheer yourself up, she says.

Chloe Haskoll, 34, says that is exactly why she bought a beauty advent calendar for herself this year.

"I'm not keen on chocolate and like the idea of a daily pick-me up. They're not cheap but I find December exhausting so it's a well deserved treat, I reckon," she says.

Chloe Haskoll says her beauty calendar will be a "pick-me up" in a tough month

Mr Caffell says beauty calendars tend to provide the best savings as they can be a cheaper way to buy a lot of products from one of the bigger brands, and any products you don't want can be given as stocking-fillers.

"Boots No7, M&S and Body Shop all have popular calendars which are worth looking out for, as you get products worth a lot more than the price of the Advent calendar itself."

Natalie Oakley, who is behind beauty blog Lady Like Momma, external, has been known to stay up for the midnight launch of such calendars and tracks the launch dates in magazines and online.

"I choose a calendar based on two things," says the writer, from Sedgley in the West Midlands. "I either go for a brand I know and love already, or brands that I am keen to try out.

"And the second thing is the style [and] packaging. I think when you are spending quite a lot on a calendar you want it to look good in your home and I personally want to be able to use it again the following year and add my own things to the drawers."

Natalie Oakley reuses her beauty calendars by adding her own things to the drawers

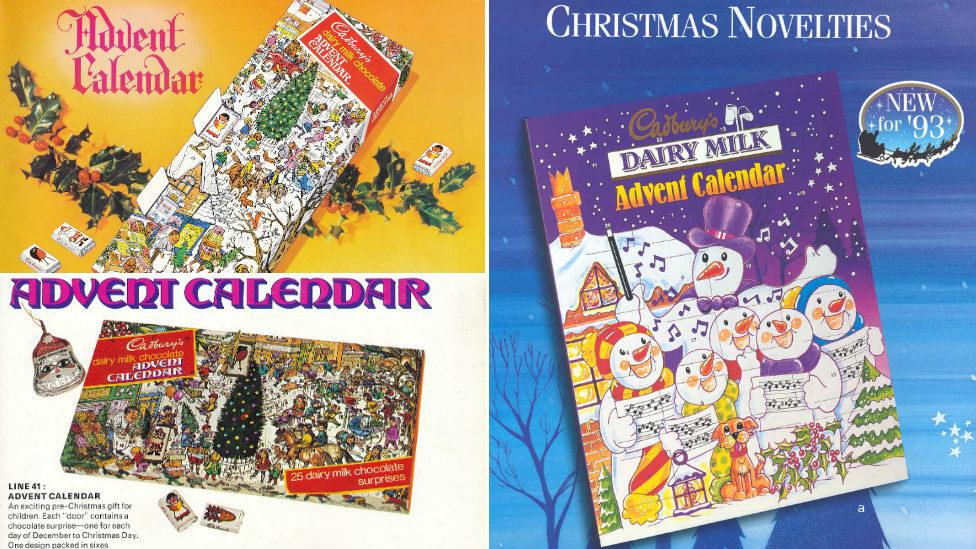

Cadbury launched its first Advent calendar in 1971, but only started producing them every Christmas from 1993

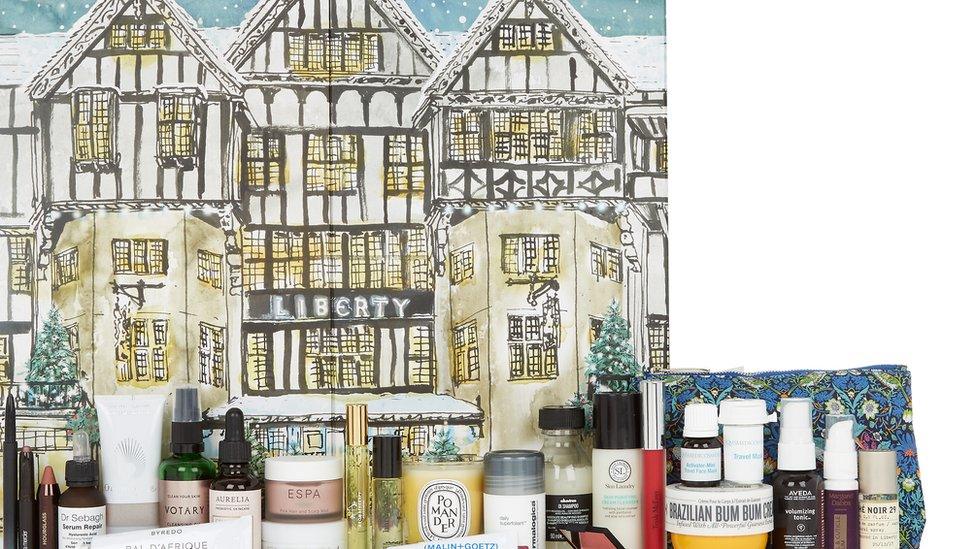

Luxury calendars are a very recent phenomenon - department store Liberty's coveted beauty calendar, which sold out online in 39 hours this year, only launched in 2014.

Even chocolate calendars only really became commonplace in the 1990s, says Alex Hutchinson, archivist and historian for Nestle.

"It wasn't until after World War Two and after rationing ended that chocolate became a more affordable purchase.

"Chocolate was so expensive that manufacturers couldn't afford to put it in an Advent calendar. By the 1960s, people got back into the habit of treating it as a grocery product but [the idea of chocolate being linked to Advent] would still have been a bit sacrilegious."

You might also like:

Cadbury's says the company launched its first Advent calendar in 1971, with production the following year and again between 1978 and 1980.

It wasn't until 1993 the firm began to produce them continuously, when it became more routinely adopted as a Christmas tradition.

But trying to marry the commercial desire to sell more during what is, after all, a religious festival, requires some sensitivity.

When bakery chain Greggs promoted its advent calendar by swapping Jesus for a sausage roll in a nativity scene, some said it had gone too far.

YouTube star Zoella also came a cropper when parents complained that her £50 12-window calendar was "overpriced tat", prompting Boots to halve the price to £25.

Greggs was forced to apologise for swapping Jesus for a sausage roll in its advent calendar promotion

There are other less obvious pitfalls for retailers.

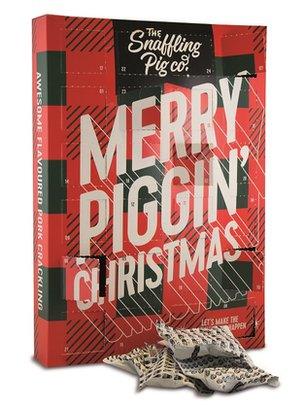

Those fiddly boxes and unusual shapes mean they can be difficult and expensive to make, something pork scratchings firm Snaffling Pig found to its cost when it launched its first calendar last year.

The firm's co-founder Andy Allen says a combination of the A3 size, which took up almost all their warehouse space; and the need to produce the calendar in a short space of time to keep the product fresh, "almost broke them".

The result was that they had less than a month to make and then post out 11,000 calendars before 1 December.

"It piled on a lot of pressure," he says.

This year, they are making about 45,000 calendars and have outsourced the fiddly filling and calendar construction to a team.

"It is a bit more controlled," he says.

Snaffling Pig struggled to make all its Advent calendars on time last year

For larger firms like John Lewis, Advent is akin to a military operation.

Head of Christmas products Dan Cooper has already picked his first set of calendars for next Christmas and across all styles, sales are up 48% so far this year.

The chain launched its own £149 beauty product calendar for the first time this year, and the 3,000 it made have already sold out.

Mr Cooper believes the growing popularity of more luxurious calendars is partly down to the ever earlier spread of "Christmas hysteria".

But he says the real shift is that calendars have become "a family thing". Advent, it seems, is no longer just for kids.

John Lewis says the Lego advent calendars are its strongest sellers

Angus Thirlwell is the chief executive and founder of chocolate chain Hotel Chocolat, which has been selling a "posh calendar" pitched squarely at adults for nearly a decade now.

He says people are generally buying calendars in addition to their usual Christmas gifts - not instead of them - and Advent has now become "a season in its own right".

"That's why we like it," he says.

But isn't festive commercialism getting a bit out of hand?

"It's difficult to take the hedonism out of Christmas, the genie has already escaped the bottle," says Mr Thirlwell.

Men outnumbered women by two to one in the queue to buy Liberty's calendar this year

Retailers, of course, say these calendars are a good deal - to the point of printing it on your receipt.

In a clever marketing ploy. Marks & Spencer's beauty calendar (which is £35 if you spend an additional £35 on non-food products), flashes up at the till at £250, which is what the company says it's worth before the price is reduced.

But customer reviews show they believe the chance to try more expensive products than they could normally afford makes them worth it.

And glowing skin isn't necessarily the only bonus. Some calendars' popularity mean they can be lucrative.

Liberty's £175 beauty calendars are now listed on auction site eBay at double the original price, for example.

The idea that shops are deliberately under-stocking their calendars to create a fake rush is a "myth" according to Mr Cooper, who adds that changing trends mean "things sometimes sell better than expected".

But however big your advent calendar is, and whatever you paid for it, there's still one big challenge left - stopping yourself from opening all those tempting little windows at once.

Liberty's £175 beauty calendars are now listed on auction site eBay at double the original price

- Published5 December 2016

- Published30 October 2016

- Published13 December 2016