Beveridge Report: How has the UK changed in the past 75 years?

- Published

Seventy-five years ago the publication of the Beveridge Report laid the foundations for the UK's welfare state. But how does today's welfare state differ from that envisaged by the report's author?

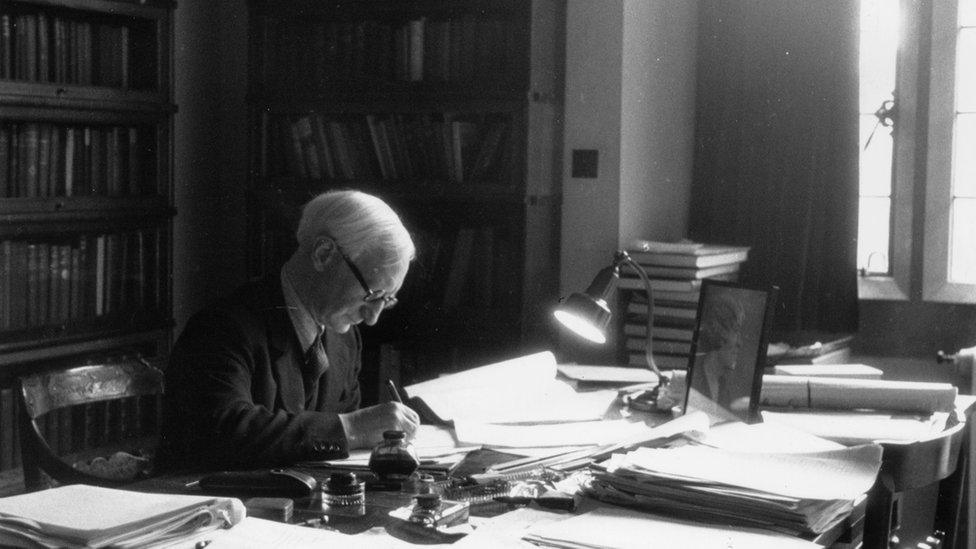

The report was launched in a different country at a different time. Today's Britain would be unrecognisable to its author, the Liberal economist Sir William Beveridge.

Commissioned the previous year by the wartime coalition government, it sought to examine how Britain should be rebuilt after World War Two and to identify the great issues faced by the country and its people.

At a very basic level, the pre-internet era meant that to read his 299-page report, you had to physically buy a copy and 70,000 were printed, costing a shilling each.

The Guardian, or the Manchester Guardian as it was then known, considered the report "revolutionary" and devoted most of its front page as well as an inside page to reporting and analysing its contents.

It's not that Sir William's "five giants" - Want, Squalor, Ignorance, Disease and Idleness - have disappeared, far from it. It's simply that their manifestation in 21st Century Britain and, how we have chosen to deal with them, have changed beyond his recognition.

Sir William built his report on Social Insurance and Allied Services, to give his work its proper title, on the simple but revolutionary idea that all people in work would pay a single weekly flat rate contribution into a state insurance fund.

The report sought to tackle the effects of unemployment

This fund would create a safety net, covering almost every eventuality that might befall an individual through life. When employment wasn't possible - a factory closure, injury, maternity, old age - a newly created Ministry of Social Security would look after people, funded by the contributions.

With his reliance on work, underpinning Sir William's proposals was the notion of full employment, which he defined as an unemployment rate of 3% or less: a goal that was quickly achieved.

By 1946, unemployment stood at only 2.5% and jumped to 3.1% the following year before remaining under 3% for decades, until 1970.

Since then, it's been much more problematic - it reached double digits in the 1980s - and even today, with record numbers of people in work, the unemployment rate is 4.3%

Work did of course mean something very different in the 1940s. The emphasis was on men having a job - the rate of women in work was much lower, around 40%. The belief was that a man in full-time work could earn enough to keep a wife and family.

An ageing population presents a major challenge to today's welfare state

Old age was also a different concept. At the time Sir William was setting out his proposals for the state to pay an income on retirement, then 65 for men and 60 for women, the average male life expectancy was only 63, so his plan didn't seem like a major financial burden to the government.

Within years, however, the costs of his ideas began to mushroom. Life expectancy, for instance, quickly overtook retirement age - in part as a result of the better healthcare he had advocated.

Pensions are now the single biggest welfare expenditure, and the overall cost and nature of social security is beyond his imagination.

Sir William never foresaw that the state would need to support wages, through tax credits and minimum wage arrangements. The thought that someone could be in full-time work and not earn enough to be able to support themselves was anathema to him.

For increasing numbers of people, work no longer pays - there are record levels of in-work poverty.

Similarly, the explosion of women working over the decades, currently at record levels of 69.7%, has meant significant change.

When Sir William spoke of single people, he meant people who hadn't married or were widowed. Divorce? Births outside marriage? Essentially only widows were single parents.

The increase in single households has been a large contributor to one of the chief challenges of our age, namely housing.

The huge increase in the number of working women has transformed the UK economy

If squalor was Sir William's target, then simple supply is today's most pressing problem. That's not to say that squalor has been eradicated, it hasn't, with hundreds of thousands of people living in often dangerously overcrowded accommodation, or being exploited by rapacious landlords, focused solely on the bottom line.

As for the tens of billions spent annually on housing benefit and temporary accommodation, the post-war willingness to build large numbers of properties shows what can be done.

The changing needs of the population also means that the greater part of the link between contributions and benefits, the basis of Sir William's reforms, has long since been ditched.

There are a few benefits that are still linked to National Insurance contributions but a failure to have paid enough doesn't leave you penniless.

Most benefits now rely on means-testing - even if you qualify, you often won't get anything if your income or savings are too high.

The rapid rise in the cost of sickness benefits was described in leaked documents a few years ago as "one of the largest fiscal risks currently facing the government".

Much of that cost is linked to rising levels of demand among people with mental health needs. Psychiatric problems are the modern-day disease, in Sir William's language, a gross health inequality that needs rapid and sustained attention.

Though spending on state education has burgeoned since World War Two, millions of people in the UK still lack literacy and numeracy skills

As for ignorance, consider this - around five million Britons will not be able to read this article, having neither the literacy, numerical or digital skills necessary to fully function in today's society.

Sir William succeeded not simply because his ideas were good and timely. The British people in the 1940s accepted - even wanted - the state to have a role in guiding and supporting their lives.

Today, many people want the government to get out of the way, to let people lead their own lives.

The enthusiasm with which his ideas were embraced were cited by their supporters as proof that government can be a force for good.

But today's solutions, to those of Sir William's evils that persist in modern form, are more complex and mean that the state can probably no longer act unilaterally and hope to achieve success.

- Published21 May 2015