The drug-smuggling fishermen vowing to clear their name

- Published

The men's fishing boat, the Galwad, has not seen the sea for years

Six years ago, a group of fishermen were convicted for their role in one of the biggest drug smuggling hauls in British history. Campaigners - and one of the original jurors - say that serious doubts remain about the safety of those convictions. Last month, the men lost an official review of their case.

On 29 May 2010, a small fishing boat left the Isle of Wight on what its crew claim was a routine trip to catch lobster and crab in the English Channel.

At the same time, a major surveillance operation was also under way, led by the Serious Organised Crime Agency - which had intelligence about cocaine being on board a giant container ship sailing from South America.

That night, one of the ships being monitored and the men's fishing boat briefly came close together - though exactly how close is still disputed.

The next day 11 sacks were found tangled around a buoy in Freshwater Bay to the south of the island, each packed with a pure form of cocaine that had a street value of £53m.

Police helicopter footage shows the white rope connecting the sacks

The prosecution's case was that the sacks were pushed off the side of the container ship for the fishermen to collect, who then took them to the bay, leaving them there to hide or be collected by another vessel at a later time.

The five men - Daniel Payne, Zoran Dresic, Jonathan Beere, Scott Birtwistle and Jamie Green - were found guilty of conspiracy to smuggle class A drugs and given sentences of up to 24 years each.

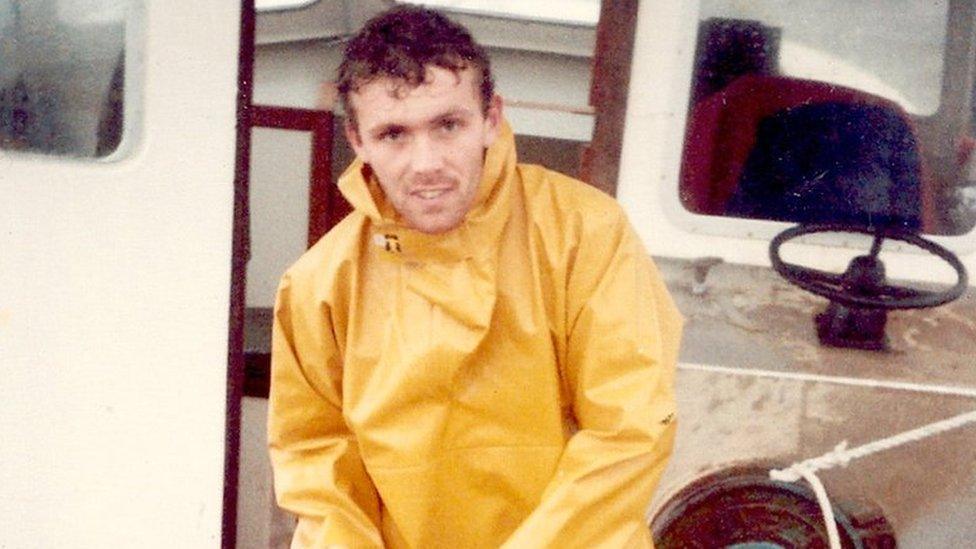

Jamie Green was the skipper of the boat, and received a 24-year prison sentence

Richard Yardley was the only one of 12 jurors in the 2011 trial to find the men not guilty.

When the verdicts were read out, he says his heart "was pounding like it was going to come out of my mouth".

"I was devastated. Even more so when I heard the reaction of the families," he tells the BBC's Victoria Derbyshire programme.

"There are lots of things wrong about that case. Loads.

"I was convinced beyond reasonable doubt at the time [that they were not guilty]. Now I'm convinced beyond any doubt whatsoever."

The men's case has been taken up by the Centre for Criminal Appeals - a charity run by Emily Bolton, a British lawyer who worked for years on death row and innocence projects in the US.

Ms Bolton says new analysis of navigational data - not seen in the original trial - suggests the container ship, the MSC Oriane, adjusted its course earlier than thought and would never have come into contact with the fishing boat, the Galwad - meaning the drugs could not have been smuggled on board.

MSC Oriane

"The implication of the tracks not crossing in this case is absolutely fundamental," she explains. "If the tracks didn't cross, they didn't smuggle the drugs."

But for the Criminal Cases Review Commission (CCRC) - the official body which investigates suspected miscarriages of justice, and decided last month not to refer the men's case back to the Court of Appeal - this isn't nearly enough.

"Their expert is now saying the little boat was 175m away from the big boat," says David James Smith, the CCRC commissioner who has just reviewed the case.

"No-one could say on that basis that the little boat wasn't in a position to collect the drugs. You'd have to remove them [the fishermen] from the area altogether to make a difference."

Lawyer Emily Bolton asks: Why was there no trace of cocaine?

A detailed forensic search could not find a single trace of cocaine on board the fishing boat. The drugs were wrapped in sealed plastic sacks but there is some evidence water leaked into the powder.

There are also questions over the testimony of two Hampshire Police officers, who - from nearby cliffs - said they saw "six to seven" dark items being dropped off the side of the boat near to where the drugs were later found.

At trial the fishermen claimed, if anything, they may have been throwing waste overboard at the time.

After the cocaine was found the Hampshire Police officers changed their entries in the official police surveillance log to closely match a description of the 11 multicoloured drug sacks and rope.

Police haul in cocaine with a street value of £53m, found off the Isle of Wight

Altering a surveillance log is allowed so officers can later clarify what was seen. But to the defence it raises serious doubts about the case against the men.

Don Dewer, a retired surveillance officer now working unpaid as an expert witness for the charity's defence team, believes it is "just not possible" that there would be need for officers to change a key fact after the event.

"From my point of view, the [fishermen] have been convicted on one piece of evidence, which I do not believe actually happened," he said.

The Hampshire officers were later cleared of serious wrongdoing by the independent police watchdog and the recent CCRC review could find no evidence of malice or serious misconduct by either the police or the Serious Organised Crime Agency (Soca).

David James Smith says the CCRC has been "extremely thorough" in its investigations

"Believe me, we've looked hard and if it was there we would have found it," says CCRC commissioner David James Smith.

The CCRC points to other parts of the prosecution case which it describes as "compelling".

As the men navigated their way through the Channel, a number of calls were made to the satellite phone on the fishing boat from a mobile handset purchased that day with a fake name.

The fishermen say a new member of the crew, a migrant worker in the UK on a false passport, had fallen ill and was trying to contact the person who set him up with the job.

Health club encounter

Find out more

Watch video journalist Jim Reed's full film about this case on the BBC's Victoria Derbyshire programme website.

Months after the guilty verdicts, Richard Yardley, the only juror to find the men not guilty, wrote a letter to the defence barrister alleging someone at Soca tried to interfere with the trial itself.

In allegations later heard in court, Mr Yardley said a Soca officer aware of the case had got into conversation with another of the jurors at a local health club.

Court documents show he claimed the juror "received extraneous information about the case" during the encounter, which was then passed on to other jurors.

This included the claim that the Soca officer said "although the agency had made mistakes during the operation, the accused were in fact all guilty".

Richard Yardley says he was "devastated" when the fishermen were convicted

But after an investigation, three judges said there was no support for Mr Yardley's allegation. They questioned his credibility and ruled his evidence could not be relied upon.

Mr Yardley is still adamant the conversation did take place.

"Nobody in that appeal court asked themselves the question, 'What has this guy got to gain by [making these allegations]... by putting himself in a position where he is interrogated for two hours?'," he says.

"Why would he go to the trouble unless what he is saying is the truth?"

'Locked door'

The decision made last month not to send the case back to the Court of Appeal at this stage does not mean the matter is settled.

According to the CCRC's latest annual report, it referred just 12 of the 1,563 cases it looked at last year, the lowest number since it started work 20 years ago.

That figure - less than 1% - has angered some miscarriage of justice campaigners at a time when the organisation's budget has been cut significantly.

"The CCRC is supposed to be the gateway to the Court of Appeal, but at the moment it's functioning as a locked door," says Ms Bolton.

Police mug shots, from top-left: Daniel Payne, Zoran Dresic, Jonathan Beere, Scott Birtwistle, Jamie Green

The CCRC rejects any suggestion that funding cuts mean it does not have the proper resources to deal with a complex case like this.

"I think we've been extremely thorough in our work," says CCRC commissioner David James Smith.

"The Court of Appeal, and therefore us when reviewing cases, are always looking for something new and that just isn't here in sufficient depth and detail in this case."

For the fishermen, there is still the chance of fresh evidence emerging which the CCRC will have to look at again.

For three of the five men a different route is available - taking their arguments directly to a judge to make a decision.

- Published19 July 2016