Derby terror plot: The online Casanova and his lover

- Published

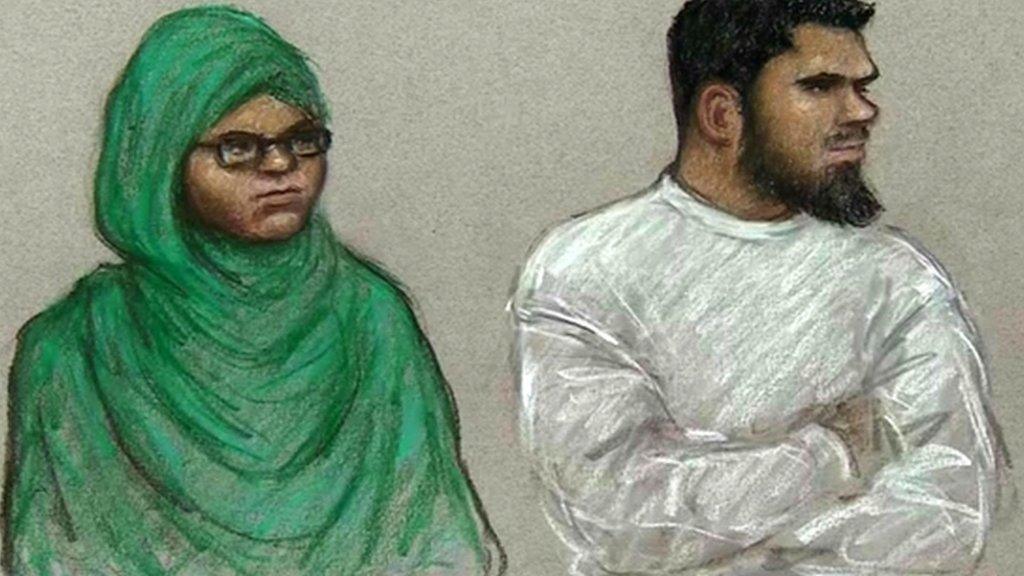

In the dock: Rowaida El-Hassan and Munir Mohammed

A couple who met online have been convicted of preparing for terrorism in a plot that could have attacked Derby or poisoned supermarket food.

Who was the man behind the plans - and why was he even in the UK in the first place?

Munir Mohammed fancied himself as a bit of a catch. He was a charmer.

He was so convinced that he was a ladies' man, Derby's own online Casanova, that he was aiming for four wives.

Even though along the way he'd abandoned the first on the migrant trail in Greece and never actually met the second.

As for the third prospective bride, British woman Rowaida El-Hassan, things didn't work out too well there either.

She found herself in the Old Bailey dock alongside him, accused of helping Mohammed prepare a major act of terrorism.

In that plan:

Munir Mohammed began buying chemicals for a homemade pressure cooker bomb

He offered himself as a "lone wolf" attacker to an IS commander communicating with him over Facebook

He investigated making poison while working at a supermarket ready-meals factory

Rowaida El-Hassan provided him with technical guidance as a trained pharmacist

And while all of that was going on, he was using a sophisticated false documents to access services and work in the UK.

Who is Munir Mohammed?

Rowaida El-Hassan came from Sudan to the UK legally as a child while 36-year-old Munir Mohammed, originally from Eritrea, grew up in the neighbouring country with his mother.

After she died, the then teenager worked in Libya, before returning to Sudan to marry.

Looking for a better life, he and his pregnant wife left for Europe in June 2013 and paid people smugglers to take them by boat across the dangerous Mycale Strait between Turkey and the Greek island of Samos.

From there they went to Athens and started to walk. And when Lana lost the baby, Munir Mohammed walked on without her, dumping her in the country.

He followed the now familiar Balkan migrant route and reached France in January 2014.

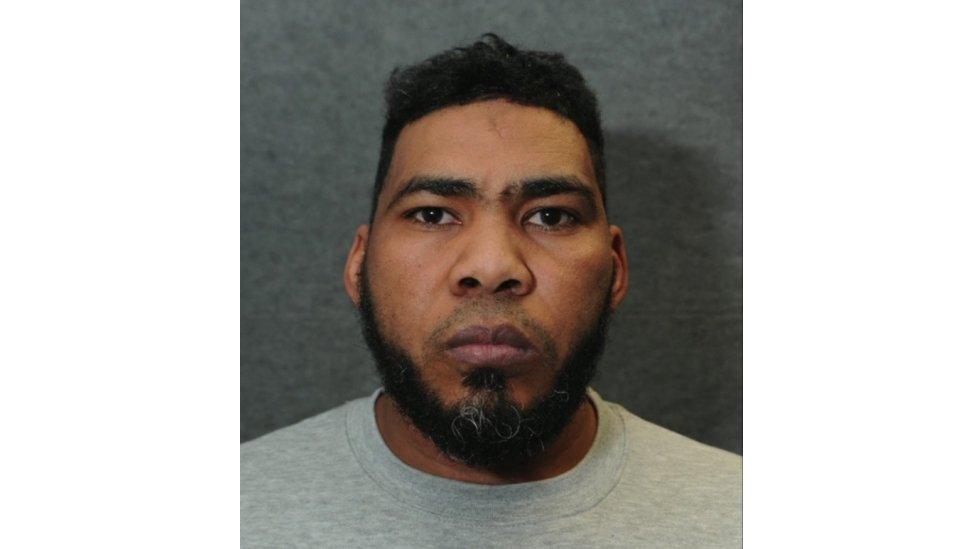

Munir Mohammed's police custody picture

Finally, he paid more people smugglers to hide him in a lorry so he could reach the UK. And he eventually emerged at a motorway services on the M1 in Bedfordshire.

Police handed him over to immigration officers - and in February 2014 he made an application for asylum. He was later released from an immigration removal centre and placed in a shared house at the Home Office's expense in Leopold Street, Derby.

Munir Mohammed wasn't allowed to work - but he wanted to earn and took a cash-in-hand job at a car wash and then cleaned at an Indian restaurant.

By May 2016 he had obtained EU documents in another man's name and secured work at Kerry Foods, a major manufacturer of ready-meals in nearby Burton upon Trent. He told the jury he cooked sauces for meals going to Tesco and Morrisons.

Kerry Foods: Munir Mohammed used forged documents to get work through a recruitment agency

During his often incoherent evidence, Munir Mohammed claimed to have been sending money to the woman he'd abandoned in Greece - but he also revealed that he had since "married" a second woman in Sudan.

The only problem is that they hadn't met. So he began looking for something more satisfying than a virtual wife, signed up to a British dating website and found Rowaida El-Hassan.

And all the time, his interest in the extremism of the so-called Islamic State was growing.

How did Rowaida El-Hassan get involved?

Rowaida El-Hassan, 32, came from a well-to-do Sudanese family. The university-educated north Londoner helped her husband grow a successful pharmacy network in Khartoum - but he cheated on her.

She returned home with her two children and began the messy process of a divorce, and looking, once more, for Mr Right.

Rowaida El-Hassan

"I am looking for a very simple, honest and straight-forward man who fears Allah before anything else," she wrote on a dating website. "I am looking for a man I can vibe with on a spiritual and intellectual level. Someone who can teach me new things and inspire me."

Munir Mohammed was a match. For three months, they chatted online and on the phone, often late into the night.

"There was emotional attachment," the chemist told her trial. "There were feelings developing. I liked the attention he was giving me."

In April, El-Hassan sent Mohammed happy pictures of her son and his birthday cake.

He sent her five Islamic State videos.

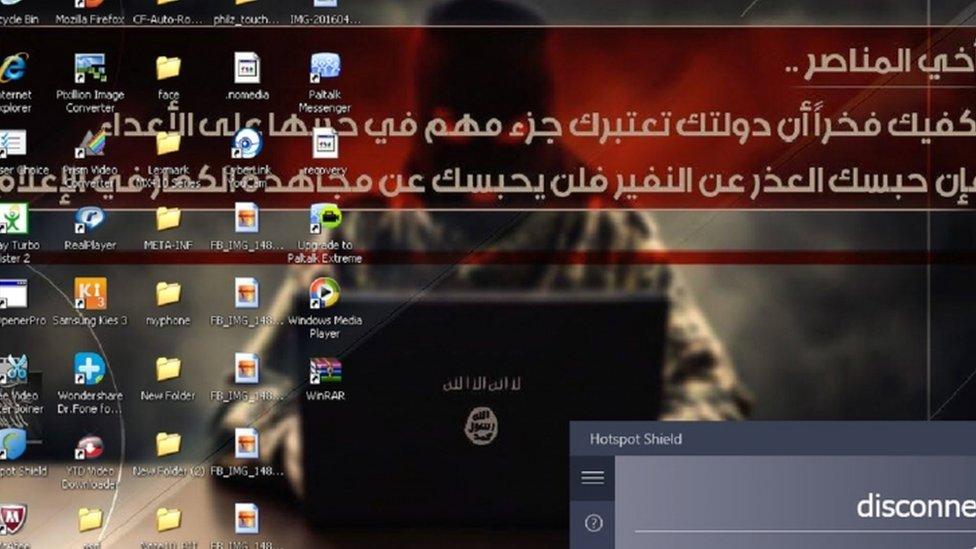

Munir Mohammed's Facebook profile

The videos weren't greeted by shock and horror. In fact, prosecutor Anne Whyte QC argued, the couple were soul mates.

El-Hassan was said to have sent her online boyfriend similar links justifying war against non-believers. As their relationship developed, the videos went back and forth - often in the small hours.

When Mohammed sent El-Hassan a shocking video apparently showing children killing prisoners, she later messaged back: 'Send me some more". The bond was growing and they eventually met.

Things were looking up for Munir Mohammed. But ever the smooth-talking player, he wasn't putting all his eggs in one basket yet.

He wasn't sure if lonely depressed Rowaida would come through for him.

He told the court that he was "allowed to marry four" and he still held a candle for his internet "wife" in Sudan - that's the one that he had never actually met.

His technique to keep her on side was less whispering sweet nothings in her ear - and more pouring extremist propaganda into her phone because he sent her the same diet of violence he had shared with El-Hassan.

In one message he wrote: "That is your homework, keep reading it until you fall asleep, and read it carefully, I mean grasp what you are reading… most importantly, read the whole thing."

Those messages, one of which came with the hashtag #support_islamic_state, were put to the defendant by El-Hassan's defence counsel, his point being that the Derby lothario was trying to radicalise and control any woman he could find.

The defendant told the court: "This is God's view and opinion… She's a bit lazy… I wanted her to read it in full."

One of Abubakr Kurdi's Facebook comments

Prosecutor Anne Whyte QC told the jury that in July 2016, while already working in a food factory, Munir was researching how to make the poison ricin - and he contacted El-Hassan for her advice. She guided him to further online research - and call logs show they then spoke for 40 minutes.

Mohammed returned again to the poison idea in November - but during the intervening months, he had also made contact with a suspected IS organiser called "Abubakr Kurdi", who, according to the defendant, was in Greece.

Kurdi - whom police say was more likely to have been in Syria or Iraq - was using Facebook to identify possible recruits for "lone wolf" attacks and Munir Mohammed was recommended by a mutual contact.

Munir Mohammed's laptop background was a picture of an online jihadi

"You just give the order," Mohammed messaged on 11 August. "Compliance and obedience to our Emir [leader]."

"I hope God will put you on the right path," said Kurdi. "We will be in contact with God's will to organise something new."

Abubakr Kurdi later posted a general appeal to his followers which read: "Inject poison in drinks or foods that are prohibited in Islam… Study different types of poison and their preparation methods… It will kill hundreds in a few moments".

More reports from Dominic Casciani:

How leaked IS document convicted Manchester dope smoker

The Birmingham lovers who said "I do" to ISIS

Could MI5 have stopped 2017's attacks?

An extremist in the family: a mother's story of loss

A month passed and Mohammed complained to Kurdi he still needed instructions. "If possible send how we make dough for Syrian bread and other types of food" he asked.

Prosecutors told the jury this was a thinly veiled code for a bomb recipe.

"We will inform you immediately how to make dough for Levantine bread if it is available where you are… I want to organise a new job for you."

As he waited, Mohammed asked Rowaida El-Hassan, a qualified pharmacist, for more help.

Shopping for ingredients

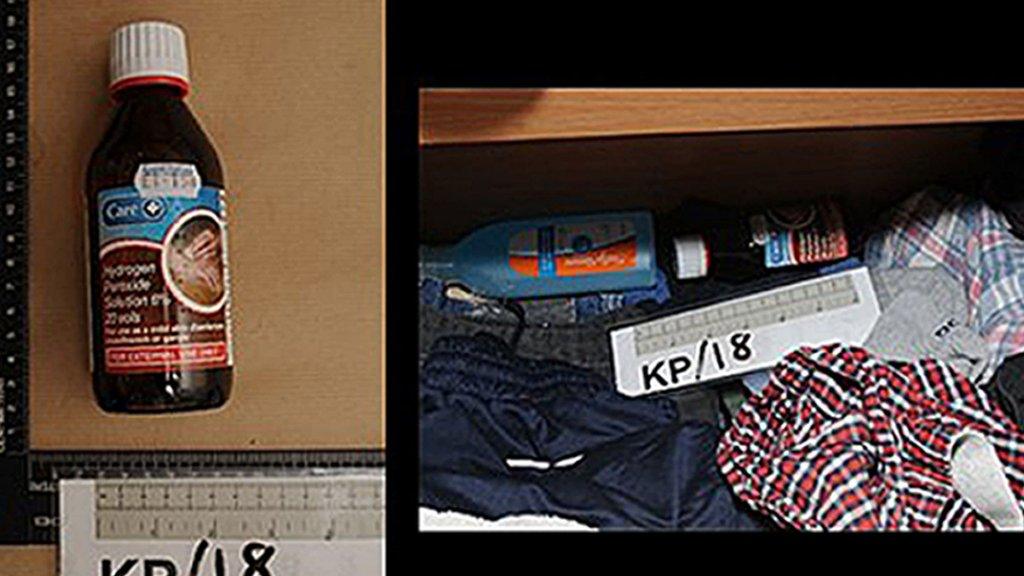

On 1 December the defendants spoke on the phone and El-Hassan then sent Mohammed a message which read "Hydrogen Peroxide" - a chemical for a type of homemade bomb recipe.

That evening, he went to Asda in Derby and, while talking to his girlfriend, looked for over-the-counter ingredients. But Mohammed didn't understand all of her advice - so while he appeared to have bought a key product for a bomb recipe, nail polish remover, the bottle had the wrong ingredients.

Shopping in Asda: Munir Mohammed looking for bomb ingredients

But even though he made this mistake, the prosecution told the trial they found hydrogen peroxide and another chemical in his home that could still have been used in a device.

While Munir Mohammed had begun preparing an attack, there was no evidence he had got any further in making ricin. He had settled on the idea of a bomb. But if he had stuck with poisons, could he have contaminated supermarket ready-meals at the factory where he worked?

Detectives say these ingredients in Mohammed's home could be used to make explosives

Detective Chief Inspector Paul Greenwood of the North East Counter Terrorism Unit, said that the risk posed by Munir Mohammed to the food supply had to be seen in context - but should not be dismissed out of hand.

"He had a viable instructional video of how to manufacture the toxin ricin, he had that know-how," he said. "He certainly was a risk, I think had that food company known, had we known of his interest in ricin and his link to that food company we would have taken steps to protect the public and to prevent him from continuing that employment there. That said we've seen no evidence that was the type of plot ultimately that he was going to pursue."

Professor Chris Elliott of Queen's University Belfast is a leading expert on food security.

He told the BBC that the likelihood of a successful poison attack on the food supply is very low.

"There are a lot of measures in place to make sure it doesn't happen," said Professor Elliott. "The amount of vigilance is really very high… it is something that is being done under the radar."

At the heart of the British system are published standards agreed between government and industry, external which are designed to identify acts of blackmail or contamination.

Why was Munir Mohammed in the UK and working?

Professor Elliott did say the Derby case could raise questions about the systems for staff vetting.

"I think the food businesses right across the UK and further afield will look at this and they will have to say, are the measures that we have in place currently robust enough? And if not, they will have to strengthen them."

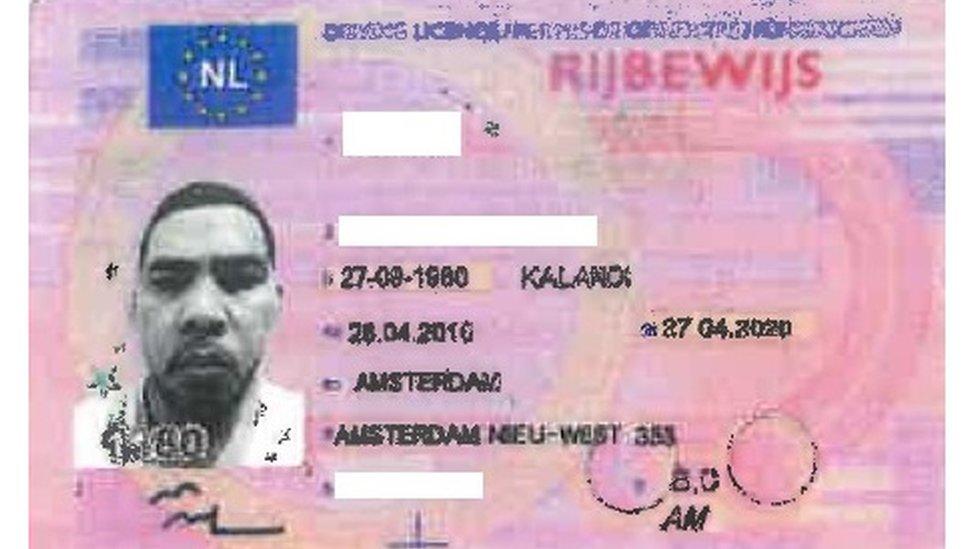

The trial revealed that defendant, who had no legal right to work in the UK, had obtained a counterfeit Dutch identity card and driving licence in the name of another man - in effect assuming his identity - but with his own image imprinted into the card. He then got onto the books of a recruitment agency, GI Group, which led to his work with Kerry Foods.

One of Munir Mohammed's fake documents. The name has been blocked out by the police.

GI Group said that its verification process, by law, requires applicants to provide documentation, checked in their presence, proving they have a right to work in the UK.

"We take our responsibilities regarding temporary worker registration very seriously and comply with all relevant obligations," said a spokesman. "In this particular case, we fully co-operated with the authorities and also commissioned an independent review which concluded that our candidate vetting procedures are rigorous and exceed Home Office guidelines regarding 'Right to Work' checks for both UK and non-UK nationals."

Kerry Foods declined to be interviewed but in a statement after the verdict the manufacturer said that it had fully cooperated with the police investigation and food safety was of paramount importance to the company.

What's not clear, however, is whether any company could have had the expertise - or indeed receives the back-up from government - to do anything more.

"If somebody is using legitimate identity documents and, in the absence of any other biometric way of screening out whether or not they are the individual contained within those documents, it's really hard for recruitment agencies to be sure that the person they're recruiting is the person with the ID," said DCI Paul Greenwood. "I would really encourage more intrusive checks and perhaps multiple forms of identity and [right to residence] to be satisfied."

So is this a major failing in the system designed by the Home Office?

It says that while it requires companies to check for illegal workers - it does not expect them to be experts in forgery - only to spot when a "falsity is reasonably apparent."

But, on top of that, Munir Mohammed's status in the UK remains totally unclear. The Home Office, the ministry responsible for both immigration and national security, won't tell us anything about it - and it won't say whether officials or ministers were aware of the Security Service's suspicions.

The evidence presented in court suggests the defendant was in a legal limbo.

Mohammed contacted the office of local MP Dame Margaret Beckett for help. She didn't meet him - but, as with many immigration cases, her team asked the Home Office to give the complainant an update. In August 2016 an official said there was now no longer a deadline for a decision on Mohammed's case because it had been deemed to be "not straightforward". And that meant his application was part of a backlog of complicated asylum claims that had grown by 40%, external since his arrival in Britain.

And so Munir Mohammed sat and waited.

And as he waited, he began to plot.