Archbishop Welby condemns populist leaders in Christmas sermon

- Published

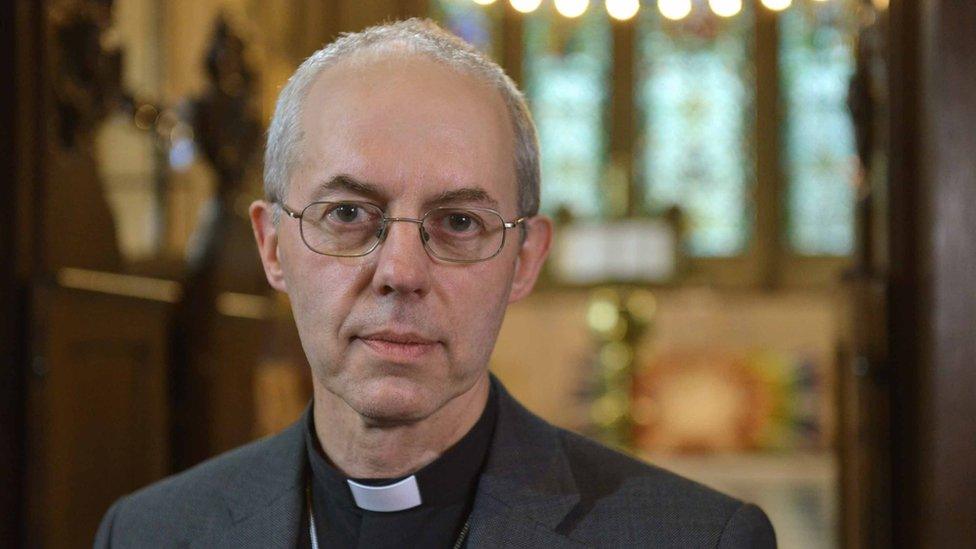

The Archbishop of Canterbury has used his Christmas Day sermon to focus on terrorist atrocities and deceitfulness of "populist leaders" in 2017.

Preaching to worshippers at Canterbury Cathedral, the Most Rev Justin Welby compared the Holy Family to modern-day refugees.

He also contrasted Jesus with "populist leaders that deceive" their people.

His Catholic counterpart, Cardinal Vincent Nichols, called for a rejection of "radical individualism" in society.

Preaching at the Sung Eucharist service, the Archbishop said that the nature of power meant those who have it, seek to hold on to it.

He said: "In 2017 we have seen around the world tyrannical leaders that enslave their peoples, populist leaders that deceive them, corrupt leaders that rob them, even simply democratic, well-intentioned leaders of many parties and countries who are normal, fallible human beings."

He condemned terrorist atrocities and those who claimed that terror was "the path to freedom in God".

Like the Pope the Archbishop drew parallels between the Nativity story and the migrant crisis.

He said: "[The Holy Family] flee as refugees, like over 60 million people today.

"Yet their story is the beginning of ours, it is an invitation to lives of freedom, found through God's freely offered love."

Conflict not dialogue

In his midnight homily, the Roman Catholic Church's most senior cleric in England and Wales warned of "radical individualism" in society and said there was "conflict in the air, not dialogue".

Cardinal Nichols added he hoped Christmas would bring "green shoots of hope".

Speaking to the BBC before the Christmas midnight Mass in Westminster Cathedral, London, Cardinal Nichols said: "In social media there's a barrage of views and once a statement or claim is made there's immediately a counterclaim, and the mode of exchange is conflict."

Cardinal Nichols was critical of social media

He added that society needs "to get over that notion that faith in God and reason are somehow opposed".

He said "the heart has reasons that the mind doesn't always understand".

When asked about the part that religion plays in conflicts, he maintained faith was not the primary reason for unrest in places like the Middle East.

"Even the conflict in Northern Ireland; reading of it it that it was essentially about religious faith, is an inadequate rather superficial meaning.

"Most conflicts are about power and territories and borders and wealth," the cardinal said.

"Often religious identity is in there in the mix but I don't think for the most part it is the key issue."

- Published25 December 2017