Finsbury Park: What led Darren Osborne to kill?

- Published

Darren Osborne has been convicted of the murder of 51-year-old Makram Ali by driving a van into a crowd outside a Finsbury Park mosque.

But why did Osborne do it? What was his motivation?

There is no easy answer because, quite simply, it is very hard to pin down the routes of radicalisation.

All the evidence shows each person who turns to violence for an ideological reason has their own reasons - but they typically fit into a list of 22 "vulnerabilities".

These have been developed by offending experts (and hotly debated by critics) in recent years.

What's clear from Osborne's case is that his personal trajectory towards terrorism covers quite a lot of these vulnerabilities.

CCTV shows the moments before a van hit a crowd near Finsbury Park mosque

The most important factor in his story could be his mental state in the months before the attack and his apparent feelings of being at a crossroads.

Osborne's partner said that, in hindsight, he was a "ticking time bomb".

He had a history of alcoholism and hadn't worked properly for years.

His partner told police that he had increasingly become something of a loner and suffered anxiety.

He had been prescribed anti-depressants and had been referred to Cardiff's NHS specialist centre which organises treatment for drug and alcohol misuse.

'Them vs us'

In the weeks before the attack in June, Osborne threatened twice to kill himself, saying that he felt worthless.

Mental health problems are increasingly being recognised by counter-terrorism experts as key factors in radicalisation.

Last November, pilot schemes linking the NHS and police to treat potential suspects with such problems were expanded nationally.

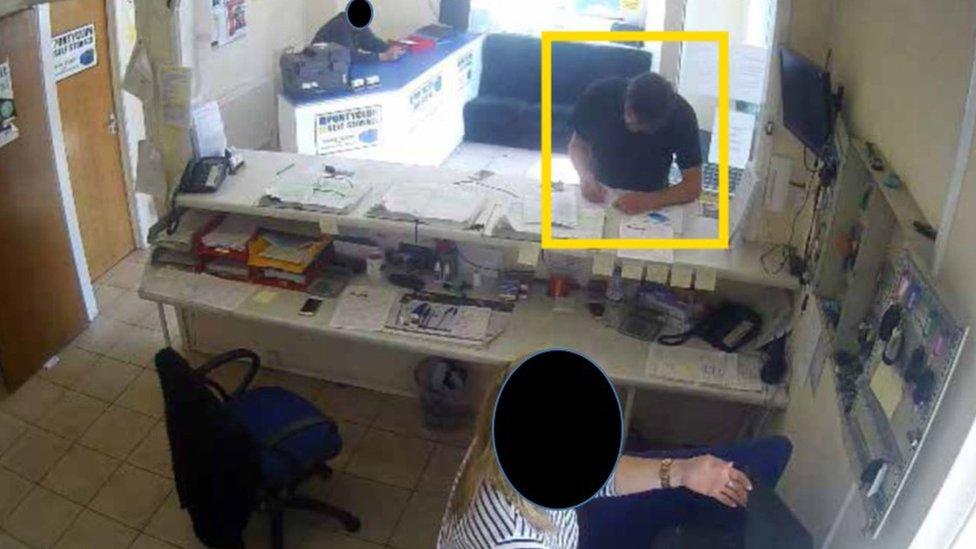

CCTV from a van hire firm near Cardiff was played in court

Osborne began to exhibit other known warning signs: he developed an irrational grievance and sense of injustice that drove him to take matters into his own hands.

It appears to have begun when Osborne became fixated on Three Girls, a three-part BBC drama about the Rochdale abuse scandal in which most of the victims were white and most of the perpetrators were Pakistani-heritage men.

His partner told police how he had become "obsessed" with the drama which aired the month before the attack. Commander Dean Haydon, the head of counter-terrorism at the Metropolitan Police, says that this drama was the "catalyst".

Osborne began accusing Muslims of being rapists or paedophiles - and the couple argued as he had never previously been openly racist or hostile to Muslims.

Jurors were shown footage which allegedly shows Darren Osborne writing at a pub table two days before the attack

These arguments appear to fit one of the most important warning signs of a potential terrorist: he developed a "them and us" view of the world.

He joined Twitter and hunted for anything to justify what he was now thinking. And this, says Commander Haydon, was the second crucial stage in Osborne's journey.

"He accessed this material and was using it to self-radicalise," said Commander Haydon. "Online played a major role in what happened. We have legislation in place that deals with [terrorist] propaganda. But some of the material that's online is unpleasant but does not cross the boundary into crime."

And it's that legal material that's in question in this case. The killer looked at content from the far-right group, Britain First, but appeared more attracted to Tommy Robinson who had previously founded and headed the English Defence League.

Mr Robinson is now an alt-right commentator who describes himself as a journalist and Osborne subscribed to his group email list.

On 22 May, Osborne received one of the emails that warned of an Islamic "nation within a nation" forming in the UK.

Osborne's letter

Osborne left a rambling letter in his van. He specifically referred to the 2017 attacks in London and Manchester, the grooming and abuse scandals and personalities who had been criticised by Mr Robinson.

He appeared to refer to a deeply controversial Iran-backed march in London, which had been his original target, again a topic that had exercised Mr Robinson.

Two days before Osborne's attack, Mr Robinson tweeted a newspaper headline referring to whether people should "look back in anger" over the Manchester bombing.

Osborne signed off his note with a sarcastic: "Don't look back in anger, God Save the Queen."

Osborne used a hired van to carry out the attack outside the London mosque

The BBC asked Mr Robinson whether his words had inflamed tensions and contributed to Osborne's state of mind.

He said that he had never heard of the killer and there had been no direct contact with him.

"This is a complete stitch [up] from the state," he said, referring to his name coming up in the prosecution's case.

Rapid path to killer

In just a few weeks, Osborne went from a troubled, angry and unpredictably violent alcoholic to a killer who was fixated on the idea that Muslims in Britain were some kind of threat to the nation.

But the speed of that transformation is not unusual.

In August 2014, Brusthom Ziamani was arrested carrying a hammer, knife and Islamic flag: he wanted to mimic the Woolwich killing of Fusilier Lee Rigby.

He had only recently become a follower of the now-jailed preacher Anjem Choudary - and the evidence suggested his further shift into violent extremism was very rapid.

In other words, it's very difficult to spot the lone would-be attackers, whatever their motivation.