South Africa: the economic challenge

- Published

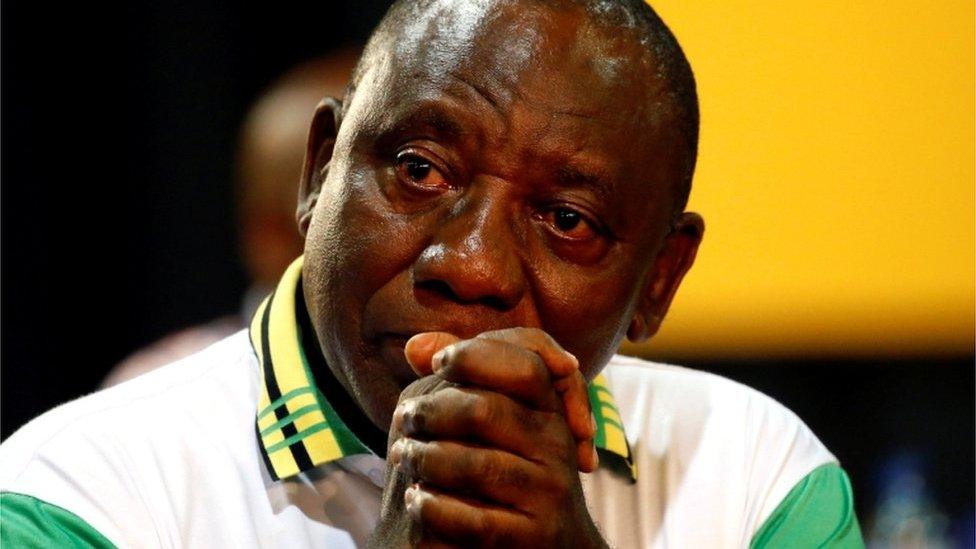

Mr Ramaphosa faces many economic challenges

South Africa's new president, Cyril Ramaphosa, will have a daunting in-tray, including a formidable economic agenda to tackle.

Growth under Jacob Zuma's leadership has been weak and unemployment is painfully high.

It is one of the most unequal countries on the planet - the legacy of apartheid is still evident.

And businesses face many barriers that make it harder to contribute to addressing these problems.

Here are some figures to set out the challenge.

Is the economy growing?

Over the last decade, the South African economy has grown at an average annual rate of 1.4%.

An emerging economy should be able to manage much better, perhaps something close to 5%.

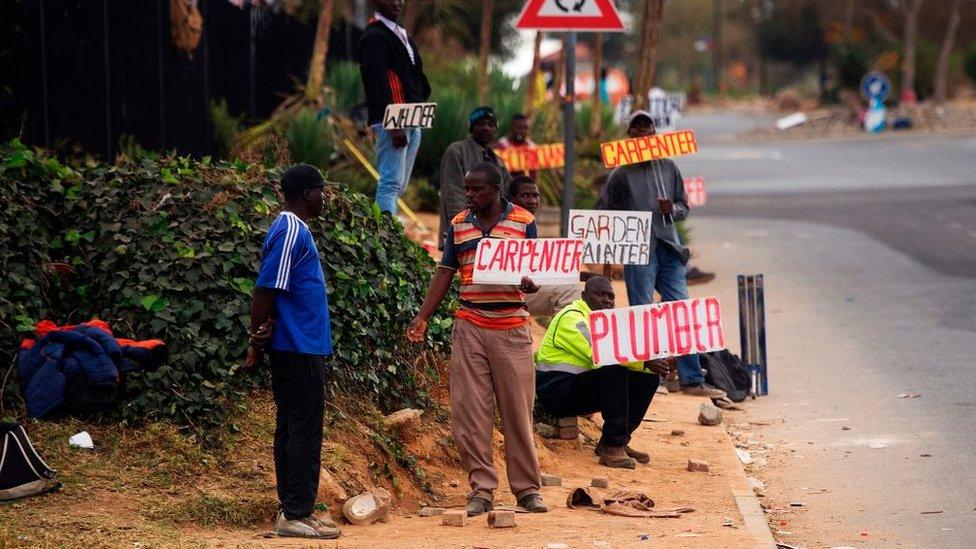

Job seekers wait on the side of a road holding placards reading their specialisation in Johannesburg

Turkey and Malaysia both have, and China, in spite of its much vaunted slowdown, has done a good deal better.

South Africa's growth in the last few years has weakened to such an extent that it's slower than the increase in population. GDP (gross domestic product) per person, which is a rough and ready indicator of average living standards, has declined.

How is wealth distributed?

The unemployment rate is worse than one in four.

The degree of inequality is extraordinary. A measure that's often used is the Gini coefficient, which ranges theoretically between zero for complete equality and 100 where all the income goes to a single person.

In the most equal countries, Nordic and some other European countries, the figure is in the mid to high 20s, for the UK it's in the mid-30s and the US around 40. For South Africa it's more than 60., external

So the new leader has plenty on his agenda.

How is land reform working out?

Land reform is an area which will be hard to resolve. Here too, South Africa's troubled history is in the air.

Enabling the black majority to own land was always an important principle for Mr Ramaphosa's ruling African National Congress.

A South African police officer and demonstrators against land grabbing, housing and unemployment in Johannesburg

But in practice it has been controversial and beset by problems. Much of the land that has been redistributed is now unproductive.

How to address that will be an important question for the new president.

As a warning for how wrong land reform can go if it's done badly, there is the disastrous example of neighbouring Zimbabwe, where it led to a collapse of agriculture and contributed to hyperinflation.

Is education up to scratch?

Education is particularly important.

South Africa's performance is weaker than it should be. Ensuring more young complete their education and acquire basic skills would make them more employable.

University of the Witwatersrand students demonstrate against fee increases

The IMF says weak educational attainment "contributes to wide income disparities and high unemployment, perpetuates the intergenerational transmission of poverty, and constrains economic growth."

In part the problem reflects the long shadow of apartheid. Many teachers received inadequate education themselves as they were schooled under apartheid.

What about shady government dealings?

There is also the big issue of corruption that has hung over the Zuma presidency.

Last year, the anti-corruption campaign group Transparency International supported, external a no confidence motion against the former President, because of what they called "the mounting evidence of grand corruption and state capture".

Quite apart from the ethical concerns, corruption can come with heavy economic costs, external, and there are concerns in South Africa that the political uncertainty surrounding the previous leader has weighed down on business investment.

Does the energy sector need powering up?

There are some key energy services that businesses need that are ripe for improvement, notably energy transport and telecommunications.

State owned enterprises are key players in these areas, and the International Monetary Fund has called, external for steps to make it easier for private sector suppliers to get involved.

The IMF says availability of power is no longer a constraint on economic activity, but more competition for the state owned utility would be useful. It could help reduce prices.

In transport, one specific issue mentioned by the IMF is that port tariffs are high and also the allocation of broadband spectrum has been a problem.

The IMF also presses for labour market reform, to make it easier for young people to get their first job, and give small firms more flexibility.

How is the debt pile to be tackled?

And there is the standard agenda for any government - including managing its own finances.

Government borrowing is quite high in South Africa and the burden of accumulated debt has risen markedly in the last decade.

Two of the three major credit rating agencies classify South African government debt at a level known informally in finance as "junk".

The budget, due next week, is likely to include tax increases.

Still, if the new president can make progress on the rest of the economic agenda and get some decent growth it would do a lot to reinforce the public sector's financial position.

- Published15 February 2018

- Published15 February 2018

- Published15 February 2018