Jacob Zuma resigns: What next for South Africa?

- Published

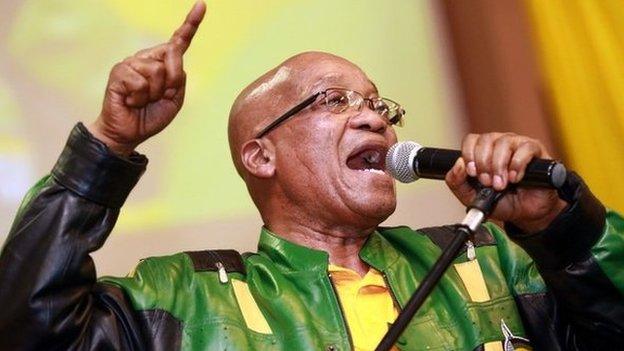

President Jacob Zuma has bowed to the inevitable after months of pressure

After years of attempts to remove him, and months of speculation, Jacob Zuma has been forced to step down as president of South Africa.

Mr Zuma had been in a vulnerable position since the end of his final term as head of the ruling ANC in December last year, when his rival Cyril Ramaphosa was chosen to lead the party.

The allegations of corruption around Mr Zuma were unrelenting.

Particularly damaging were the ongoing claims that a wealthy family from India - the Guptas - had gained lucrative state contracts and exerted undue influence on government appointments because of a corrupt relationship with the president.

While the Guptas and Mr Zuma consistently denied the claims, the stories of what is known as "state capture" kept coming.

Mr Zuma is also facing the possible reinstatement of 18 charges of corruption, fraud, and money laundering stemming from a 1990s arms deal.

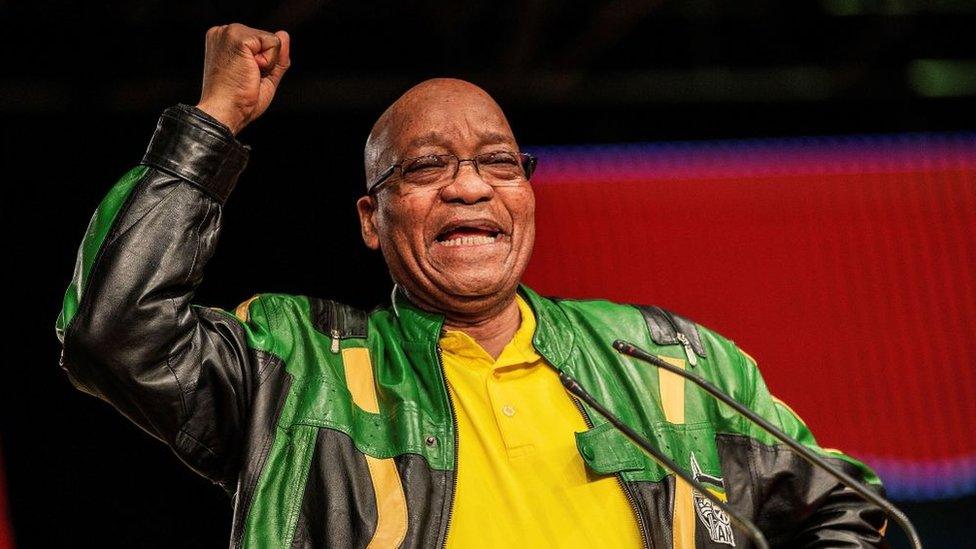

Cyril Ramaphosa has been eyeing the presidency for a long time

What next for Ramaphosa?

Mr Ramaphosa has been sworn in as the country's new president after he was the only candidate in an election in parliament.

He has said his priority is reviving South Africa's battered economy. Shortly after winning the bitterly contested ANC leadership battle, he said "we must all do all we can to ensure that we turn our economy around".

But it won't be easy: Unemployment is currently at almost 30%, a rate which rises to nearly 40% for young people. Low growth rates and dwindling investor confidence were compounded by two credit agencies downgrading the economy to junk status.

One of the first steps in improving that investor confidence is addressing the persistent claims of corruption at the heart of government.

For example, there are the ongoing allegations of maladministration at the state power company Eskom, which led to a crisis that Finance Minister Malusi Gigaba warned could wreck the economy if not resolved. Ratings agencies have also cited the situation at the company as a cause for concern.

At the same time, Mr Ramaphosa urgently needs to unite his party. The recent leadership campaign deepened fractures within the ANC, and it is now split between those who support Mr Zuma, and backers of Mr Ramaphosa who wanted Mr Zuma out.

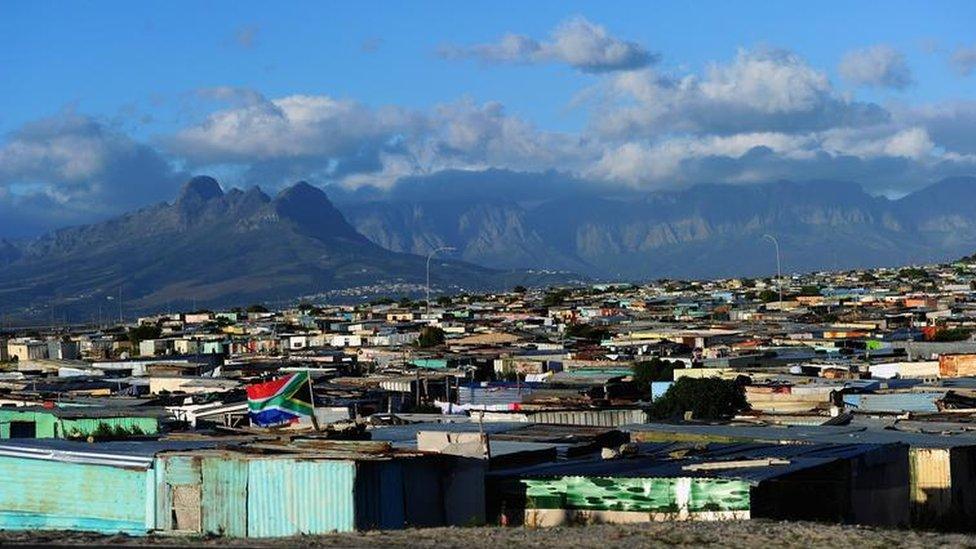

The ANC has become a fractured party

Arguably one of Mr Zuma's greatest achievements was calming the political violence in his home province of KwaZulu-Natal (KZN) during the run-up to the first democratic election in 1994. He is hugely popular in the region and is credited with delivering votes both from the area and from his Zulu ethnic group.

There are fears that if Mr Zuma's supporters feel he was treated badly, the ANC could lose these important votes. And even more concerning is that as the power struggle within the ANC has intensified, so too has political violence in KZN.

Perhaps this is one of the reasons Mr Ramaphosa was so careful in his handling of Mr Zuma's exit, insisting on several occasions that he should not be humiliated.

It is often said that Mr Ramaphosa has had his eye on the position of president since the ANC came to power in 1994.

The story goes that he was so upset at not having been chosen by Nelson Mandela as his successor that he left politics and went into business.

But Mr Ramaphosa has now finally realised that dream. But unless he is able to bring Mr Zuma's supporters on board, and address the issues in the economy, his time as president could prove to be short-lived.

What next for the ANC?

The ANC has won every election in South Africa since the end of white minority rule in 1994. For many South Africans it is the party that brought them freedom from the brutality and racism of apartheid rule, and this is not something easily forgotten.

But its popularity has been waning, and for the first time there is a realistic possibility that the party could lose power - particularly if the opposition parties form a coalition.

The ANC suffered humiliating losses in the 2016 local government elections. Although it gained far more votes than any other party, it lost control of major cities including the economic hub of Johannesburg and the capital, Pretoria.

While there is no doubt that the lives of many South Africans have improved, many feel not enough has changed under ANC rule. South Africa is still one of the most unequal countries in the world, and more than half the population live in poverty.

The ANC's challenge: How to please its base without losing investor confidence

The allegations of corruption within the ANC government have added to a sense that a privileged, politically connected elite is benefitting at the expense of ordinary South Africans.

There is also the sense among many black South Africans that the power structures created under apartheid are still in place. In particular, land and the economy are hot button issues.

The redistribution of agricultural land taken from black people while the country was under white rule has been painfully slow.

About 95% of the country's assets are in the hands of 10% of the population. And white South Africans still earn around five times more than their black counterparts.

The ANC has promised to accelerate land redistribution - even promising to change the constitution to allow land expropriation without compensation. And it has adopted the policy of "Radical Economic Transformation" - putting economic power in the hands of the majority black population.

But if it wants to retain that all-important investor confidence, the party also needs to convince business that South Africa will not go down the road already trodden by Zimbabwe.

Balancing the interests of its core voters with those of business and the economy might prove to the biggest challenge for the ANC ahead of the 2019 election.

- Published6 April 2018

- Published17 June 2024

- Published21 December 2017

- Published14 February 2018

- Published19 December 2017