London killings: No easy answers to gun and knife crime

- Published

The deliberate killing of one human being by another is a crime that defies easy characterisation.

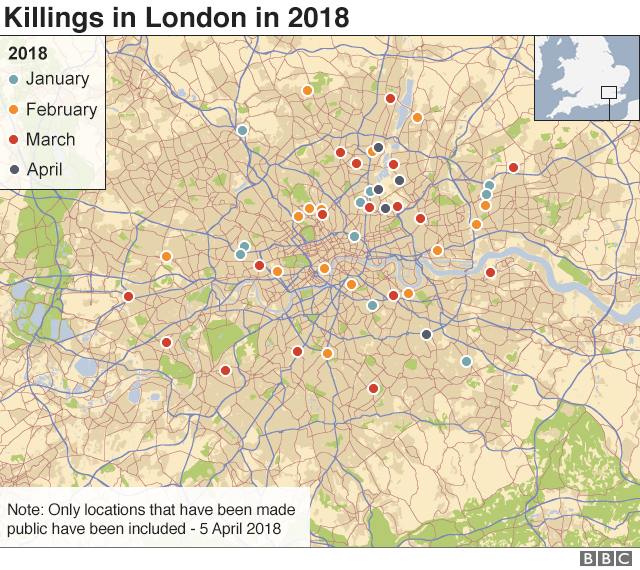

Among the more than 50 tragedies that make up the current spike in homicides in the capital this year are some that may be premeditated or gang-related, but most will be unpredictable acts of violence in moments of mental anguish, involving a victim and a perpetrator who are well known to each other - family disputes or an argument between friends.

By far the most likely year of life in which we might be unlawfully killed is not in our teens or early 20s but our first year - babies under one are more than twice as likely to be murdered as a 20-year-old.

That is why it is far too simplistic to draw a direct link between the number of killings and the number of Bobbies on the beat. Cuts to police budgets may be less relevant than cuts to mental health provision.

In tackling gang activity, there is good evidence that a psychiatric health approach may be more effective than a tough criminal justice response, which can thwart individual acts of violence, but may also infect communities with resentment and distrust - the breeding ground of gangsters.

Analysis of a survey of more than 4,600 young men in the UK, published in the American Journal of Psychiatry, found those involved with gangs showed "inordinately high levels of psychiatric morbidity, placing a heavy burden on mental health services".

The authors concluded that "healthcare professionals may have an important role in promoting desistence from gang activity".

Separate research involving long and detailed interviews with 16 men on death row in the US found all had experienced family violence. Fourteen of the men had been "severely physically abused as children by a family member".

Three of them had been beaten unconscious. Twelve of the death row inmates had been diagnosed with traumatic brain injury.

The World Health Organization in Europe found a similar link: "Exposure to violence and mental trauma in childhood is associated with atypical neurodevelopment and subsequent information-processing biases, leading to poor attachment, aggression and violent behaviour. Children who experience neglect and maltreatment from parents are at greater risk for aggressive and antisocial behaviour and violent offending in later life."

Killing can be contagious. The murder of one young person can raise fear levels on the street, making it more likely others will carry weapons to protect themselves. And more likely they will use them.

Fact checking murder statistics in London vs New York

In the US and increasingly in the UK, in places like Glasgow, agencies are successfully reducing gang violence by treating it in the same way they'd respond to a public health emergency, looking to disrupt the spread of a deadly virus.

Karyn McCluskey, a former director of Violence Reduction Unit set up by Strathclyde police, says it is about identifying the people at risk.

"We need to interrupt because some people are very angry and sometimes they'll be on their phone, plotting their revenge," she says.

"Often these are people that need to be rehoused, who need drug addiction services, so it's about connecting them to all the other services that are out there and staying with them."

Self control

The general murder rate, though, is immune to quick and easy interventions. Declining for centuries, it is a reflection of deeper trends - society's relationship to violence and the mental resilience of a population.

Back in the Middle Ages, according to analysis of English coroners' records and 'eyre rolls' (accounts of visits by justice officials), the rate was around 35/100,000. This is equivalent to the homicide level in contemporary Colombia or the Congo.

From the middle of the 16th Century, the homicide rate starts to fall steeply, a dramatic reduction in risk that is maintained for 200 years. The development of a statutory justice system is often cited - but it was also a period in which society found alternative ways of dealing with dispute and discontent.

For Europe's elite, the duel emerged as a controlled and respectable way of responding to an insult against one's honour. Spontaneous violence became disreputable for gentlemen of standing while personal discipline and restraint were seen as the marks of a civilised individual.

The murder rate continued to fall, if less steeply, during the 19th and 20th Centuries as state control and social policies increased. It was also partly a consequence of young men being given a substitute for interpersonal violence to demonstrate their masculinity - organised sport.

Boxing, for example, developed from bare-knuckled no-holds-barred brawls to disciplined contests governed by a strict code and overseen by a referee. The 'Queensbury Rules', introduced into British boxing in 1867, became shorthand for sportsmanship and fair play. Society at all levels increasingly valued the virtue of self-control.

Close study of the vital signs of British society reveal a slight rise in the homicide rate over the past 50 years, but in historical terms the figures are still so low that a single appalling occurrence - a terrorist attack or the murderous activity of a serial killer like Dr Harold Shipman - can skew the data.

In international terms, the UK is among the less likely spots to be murdered: our homicide rate is broadly in line with other European nations (a little higher than Germany but slightly lower than France) and roughly a quarter of the level in the US.

It is right to be alarmed by the spate of tragic murders in London this year, but just as the cause of such killings are complex, the solutions to societal violence are complex too.

- Published5 April 2018