Can Scottish police help stop violent deaths in London?

- Published

There were 116 murders in London in 2017, of which 80 were fatal stabbings

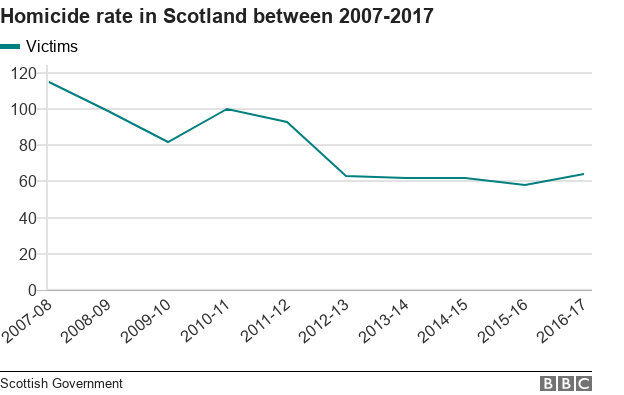

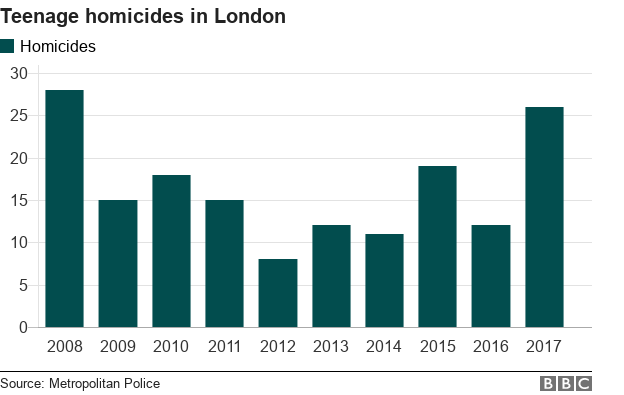

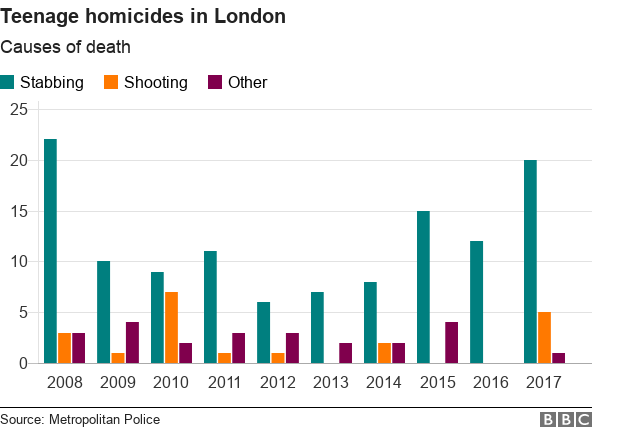

The number of teenagers being killed in London has returned to its worst levels since 2008, prompting calls for fresh ways to combat violent crime. Thirteen years ago, Scotland had one of the worst murder rates in western Europe, but a new approach has seen cases almost halve. Could the same approach work in the capital?

During 2004/05 there were 137 murders in Scotland, external, giving the country its highest number of homicides in almost a decade. In Glasgow, there were 40 cases alone - double the national rate.

It was this peak which spurred Strathclyde Police to set up the Violence Reduction Unit (VRU) in 2005, a specialist team tasked with preventing violent crimes rather than solving them.

By viewing violence as a disease, external, its goal was to diagnose the problem and treat its cause - adopting a so-called "public health approach" which saw officers working with teachers, social and health workers to collate and share knowledge of people involved in gangs.

"If you carry a knife, you intend to use it"

Between them, they made lists of those they thought had been drawn into a criminal lifestyle and indentified would-be offenders who might help violence spread.

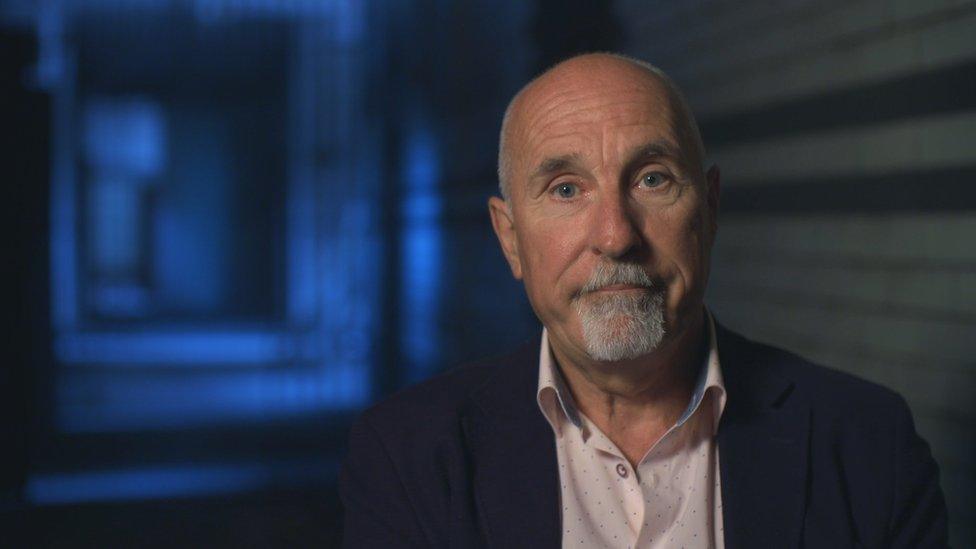

"The lists were never the same and that is because we all saw people in different lights," said John Carnochan, who spent the last seven years of his four-decade policing career leading the unit.

"By sharing this information we increased our knowledge within the community."

Potential gang members were encouraged by the VRU to attend sessions aimed at preventing future violence.

Locations and pictures of those involved in gangs were shown to them with a clear message - police knew who they were, what they were up to and that prison would soon beckon if they continued down a violent path.

They were offered an alternative - job opportunities, housing, training and mentoring - in order to break the cycle of repeat offending.

"Most young offenders are fathers, or they are soon going to be," said Mr Carnochan.

"We needed to break the cycle of children seeing their parents in a bad light, because that is what they learn from."

John Carnochan led Scotland's Violent Reduction Unit approach

The decline in violent crime in Scotland has been dramatic.

Since 2007, it has dropped by almost half , externaland crimes involving a weapon is down by two thirds, with Glasgow accounting for a third of the decrease.

The success of the VRU, which received £7.6m in Scottish government funding between 2008 and 2016, has in recent months caught the eye of London Mayor Sadiq Khan, who set up his own knife-crime strategy in June and in November launched an anti-knife crime campaign.

"I have been clear that knife crime is not something that can be solved by the police or criminal justice system alone," he said.

"We have learned the lessons from Scotland and elsewhere, where a public health approach has been very effective."

Although Glasgow and London are difficult to compare in terms of size, population and the way crime statistics are reported, both cities have experienced high levels of violent crime.

There is more knife crime in London than anywhere else in England and Wales, according to new figures, with the Met Police showing the biggest increase of recorded crimes.

The force's own statistics reveal there were 116 murders in London in 2017, of which 80 were fatal stabbings. Teenagers accounted for 26 deaths, of which 20 involved a knife.

Teenager Tyler Dawson had his leg amputated after being stabbed

Kerry Dawson, whose teenage son Tyler had his leg amputated after being stabbed in the groin in Dagenham, fears London's violent culture, particularly among teenagers, is "out of control".

The 46-year-old believes the Scottish approach is something London's force should investigate.

"Kids carrying knives and being violent is now fashionable," she said.

"There is no trust between kids and their parents, between kids and their teachers, between the kids and police.

"Kids go out on the streets and think they are untouchable, they don't care about the law.

"Something needs to be done. If that approach can work in Scotland, it can work down here."

Scotland's public health approach to knife crime has caught the eye of Sadiq Khan and the Met's commissioner Cressida Dick

Mr Khan has said parents, families, teachers, schools, youth clubs and social workers must all "play their part" in tackling violent crime.

The Met's commissioner Cressida Dick has expressed admiration for Scotland's "well-evidenced" approach but maintained London's communities and issues with violence were not the same.

"There are very different communities, very different dynamics and very different issues around violence and, indeed, youth violence," she said.

"But, nevertheless, there have been massive reductions in violent crime."

Mr Carnochan disagrees, saying crime "should not be segmented" and that "violence is violence".

"People in Scotland and London are more similar than you think," he said.

"The causes of violence stem from poor education, addictions, bad role models, absent father, mum with different partners - exactly the same in Glasgow.

"Ethnicity has little to do with violence. You need to look at the bigger picture - what is violence? People don't wake up in the morning thinking 'I am going to be violent today'.

"The Met regularly puts photos of knives on social media which have been taken off the streets, all this does is invest in fear."

Mr Carnochan feels teenagers see these images and think they need knives for protection.

"Everyone knows what a knife looks like, but because people conform to what they see these kids see the photos of knives and feel frightened," he added.

The Met Police recently held a knife amnesty where hundreds of weapons were handed in

Ken Marsh, chairman of the Metropolitan Police Federation, warns of challenges facing the Met, including the loss of officers which he believes will weaken trust between youths and police.

"I'm not against what Scotland has done at all, I admire what it has done," he said.

"But what the problem is, the numbers in our police force are going to be depleted over the next two years, sliding to 2,500 [fewer] officers than we have now.

"The squeeze will be on the community officers more than anything else."

Croydon Central MP Sarah Jones, who chairs the all-party parliamentary group on knife crime, has spoken out about the "escalation of violence among young people".

She believes the VRU has "exactly the right approach" and public services should work together to prevent youths carrying a weapon in the first place.

Sarah Jones says Scotlands's public health approach is "exactly what London needs"

"Knife crime goes up and down, just like an epidemic," Ms Jones said.

"We know that violence breeds violence. We need to act now before it spirals out of control."

- Published18 July 2019