James Landale: What next for the Commonwealth?

- Published

The Queen has long been an enthusiastic supporter of the Commonwealth

This week thousands of people will descend on London from all corners of the world, pilgrims coming to worship at the altar of post-colonial multilateralism that is the Commonwealth of Nations.

They will be drawn to the UK's capital for the organisation's biennial heads-of-government summit, known by its inelegant acronym, CHOGM.

It will be an enormous jamboree, with most of the Commonwealth's 53 leaders expected to attend - the largest number ever - in honour, perhaps, of Her Majesty the Queen, whose last CHOGM this is likely to be now that her travelling days are coming to an end.

And with the leaders and their spouses will come the officials and protection officers, the charity workers and think-tankers, the lobbyists and journalists, and all the other hangers-on in this riotous caravan of global diplomacy.

But to what end? For what purpose will these many thousands gather for what some officials estimate will be the largest summit ever held in London?

Still relevant?

For many of the 2.4 billion people who live in the Commonwealth, the organisation plays little role in their lives. They might know it as a post-imperial club, a body that holds global sporting events such as the games in Australia that have been going on over the past two weeks.

Or perhaps they have family or personal connections with another Commonwealth country. But even those with a keen awareness of the international organisation might struggle to explain what relevance it had to their daily lives.

Yet the Commonwealth includes about a third of the world's people. It forms layer upon layer of intermingling networks of professional, sporting, business and cultural groups.

It provides a forum for co-operation between nations, a bastion - at least in theory - of the democratic, rules-based international order, with the English language and legal system forming a core denominator for many countries.

And it is an organisation that the Queen values highly and has fought to protect during her long reign.

So why is a body that has so much potential so much in the shade?

One reason, perhaps, is that it has always been in search of a role. This is a Commonwealth of nations that was united at first by nothing more than a past membership of the British Empire.

Shared experience is one thing but it is rarely a foundation for future co-operation, particularly when that shared experience was distant, at times painful and not of mutual benefit.

The Commonwealth has also often been divided between what historically had been seen as the white, Anglocentric nations - "the ABCs" as they are known after Australia, Britain and Canada - and the African members, and the many small island countries.

And these divisions have at times been deep, not just between wealth and geography but also between culture and values. Let us not forget that 36 of the 53 countries retain legislation that criminalises homosexuality.

Trading vision

CHOGM this week will undoubtedly be overshadowed by events in Syria. But beneath the diplomacy and ceremony, there will also be some tough questions about what the Commonwealth is for in the 21st Century. And many countries will bring different answers and agendas.

Some British politicians look to the Commonwealth as a post-Brexit lifeboat, a multilateral organisation through which they can improve trade links outside the EU. And why not use this shared language, law and regulatory commonality to boost trade?

Supporters point to what they call "the Commonwealth effect", the idea that trade between members is cheaper and easier. The Commonwealth Secretariat estimates that bilateral trade between members costs about 19% less than global averages.

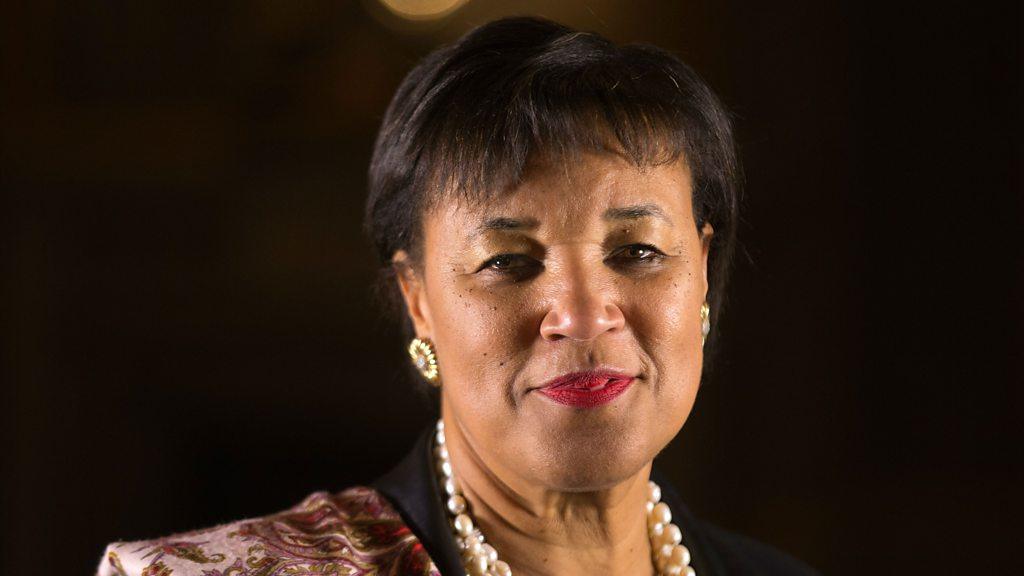

Former attorney general Baroness Scotland is the current secretary-general of the Commonwealth

But while the British Empire was initially a trading empire, the Commonwealth is a different beast. And some members might resent being showered with love by a country that has often seemed to ignore the Commonwealth while its geopolitical and economic focus was on Europe.

Many Commonwealth countries opposed Brexit. Some fear they will find it harder to access British markets. Others worry they will lose a powerful advocate for their rights around the EU table. After Brexit, the only Commonwealth countries remaining in the EU will be Cyprus and Malta.

Indian influence

Other countries see the Commonwealth as an international club with huge soft power potential.

Take India. For years it has been a restrained member of the Commonwealth, despite being one of its largest economies and containing about half its population.

India was one of the eight founder members but it was the only one which did not count the Queen as its head of state. It has always been cautious about engaging fully with the offspring of an empire that rendered its countrymen subject to British rule. But now India appears full of enthusiasm., external

Could Narendra Modi use the Commonwealth to win influence at the expense of China?

Narendra Modi will attend CHOGM, the first Indian prime minster to do so for almost a decade. Indian diplomats are suddenly appearing at Commonwealth events and meetings.

Officials say this is because India sees the Commonwealth as an organisation through which it can project influence within Asia - this one club that India's great rival, China, cannot join.

The UK seems willing to play along with this. British diplomats say that one way the Commonwealth could thrive, and - yes - survive, as a credible international organisation would be to embrace India.

To that end, the UK appears ready to contemplate greater decentralisation, with India possibly taking greater responsibility for the Commonwealth's trade co-operation.

But is this what the rest of the Commonwealth wants - to swap Anglo-centrism for Delhification? If you are from a developing African country or a small island nation in the Pacific, is this how you see the future of the organisation?

Introspection and uncertainty

Many of the smaller nations, for example, are looking to the Commonwealth to help them tackle the climate change that threatens them with rising sea levels and extreme weather events.

We may be horrified by the growing tides of plastic floating across our oceans but to many island nations this poses an explicit danger to their maritime and tourist economies.

The Commonwealth could help in a tangible and practical way to share best practice and form coalitions to protect these members from this environmental threat.

It's not guaranteed that the Prince of Wales will become the next head of the Commonwealth

Underlying this latest bout of Commonwealth introspection is the largely unspoken uncertainty about what happens when the Queen's reign comes to an end. There is a lack of clarity because it is not automatic that the Queen's heir, the Prince of Wales, will replace Her Majesty at the head of the Commonwealth.

The decision is entirely in the gift of the heads of government at the time. This CHOGM will be a forum to discuss - sotto voce - what should happen.

The British government appears ready to allow just enough debate to ensure that Prince Charles is established as the de facto heir apparent.

But the UK equally does not want this to become a distracting row that could embarrass the Queen - something shadow international development secretary Kate Osamor has made a forlorn hope.

She told The House magazine bluntly , externalthat the role should not be taken up by Prince Charles but by someone who was "level-headed, someone people respect".

This matters not just because officials want to ensure a smooth transition, but also because the Queen has been so central to the Commonwealth that her absence could create a vacuum.

Her leadership has been part of the glue that has held this organisation together.

The risk is that without her, the Commonwealth could come unstuck. Hence the need, once again, for the Commonwealth to change and find a new role for the 21st Century.

- Published24 August 2017

- Published26 January 2017