Tragedy and hidden meaning behind Britain's makeshift memorials

- Published

Symon still paints the bicycle - left to mark his son's death in 2013 - and a gardener tends flowers

Symon Squire's weekly journey to his parents' house always comes with a tragic reminder.

The drive takes him past the spot where his teenage son, Daniel, was killed while cycling near Ringwould, a village in Kent.

The busy roadside location is marked by a bicycle, painted white, which is surrounded by flowers.

"As his dad, it's tricky going past," says Symon, a warehouse manager, who set up the memorial shortly after 18-year-old Daniel's death in 2013.

"When you drive through, you sort of say hello to him. And it tells people, there was an incident here - slow down. It is quite striking."

He is one of many people who maintain makeshift memorials across Britain.

But what forms do they take - and are they helpful as a way to cope with grief?

Signs of sadness

Bouquets, crosses, balloons, pictures and other personal items - these memorials are typically left where someone has died in tragic or unexpected circumstances.

Some can divide communities.

Locals tore down flowers left near the south-east London home where Henry Vincent, a suspected burglar, was stabbed and killed last week.

A man was seen stamping on flowers and balloons left in tribute of Henry Vincent

Last year, an impromptu pavement memorial to a teenager killed while riding a stolen motorbike was set up in Henbury, Bristol.

Flowers and candles were left for 18-year-old Adam Nolan, who was a passenger on the bike being driven by a 14-year-old boy.

But after it went up, it was vandalised.

'Ghost' bicycles

Symon's "ghost bicycle" tribute to Daniel - who was hit by a van on a busy main road - could be pulled down at any point.

"I had to be a bit careful about it," says Symon, whose bicycle is on land owned by the Environment Agency.

"I was going to put a plaque there to say what happened but didn't want it to be too personalised."

Crash site inspires a stage play

Dedicated memorials typically require the permission of the local authority or landowner.

A ghost bicycle in Hackney, east London, for 28-year-old Shivon Watson, was removed by the council in 2013 after it said it received complaints.

And last year, Bath & North East Somerset Council removed a ghost bike for Jake Gilmore, 19, who was killed in 2013.

Some ghost bikes, though, are given official status.

Former London mayor Boris Johnson allowed a permanent white bicycle in Notting Hill as a tribute to Eilidh Cairns, set up by her sister Kate Cairns.

Coping with grief

Five years on, Symon paints the bicycle twice a year and pays a gardener to tend flowers.

The visits are painful, he says, adding that he and wife Tracy moved to "get away" from the site, which was 400 metres from the family home.

"I still feel a connection to the last place he ever was, the last place he was alive," he adds.

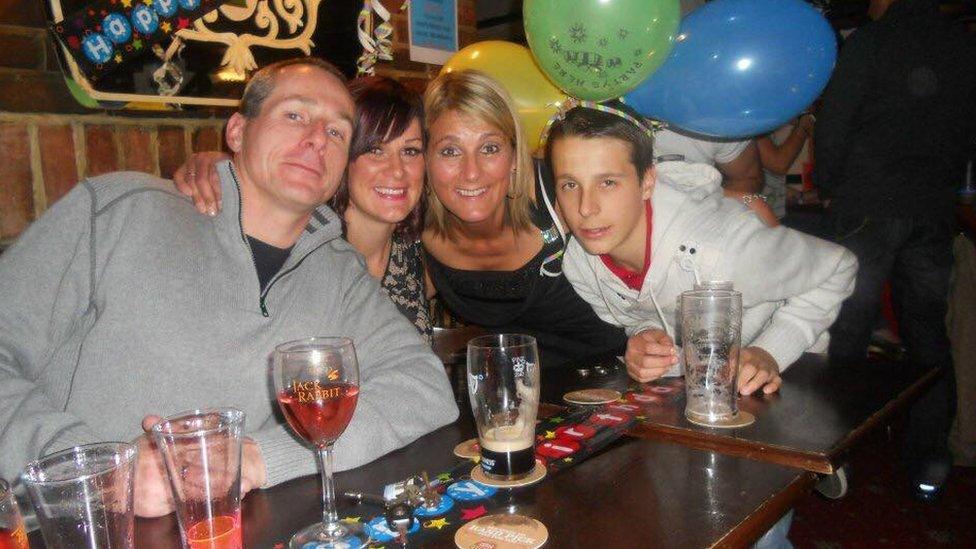

Symon Squire, pictured with Daniel's sister Hayley and mum Tracy, and Daniel

Bereavement counsellors say going back to the scene of a tragedy can be a healthy part of the grieving process.

"Leaving flowers or items of meaning at the site of a sudden death is a powerful way to actualise a loss," says therapist Michelle Brown.

She says there is no "right way" to grieve, but that visiting the site can help overcome the disbelief that goes with a tragic loss.

Paul Finnegan, from the bereavement counselling charity Cruse, says: "Everybody is different, but I would never say 'do not leave flowers' or whatever else that individual feels is special."

He says there is a "certain poignancy" to public memorials.

"We wouldn't necessarily leave flowers outside a hospital ward where someone died," he says.

"Public memorials act as a sign to other people to say: 'This is someone who's died who's really important to me.''

Memorial, or political point?

Memorials can even be left spontaneously, by those who never met the person who died.

Princess Diana was remembered in an unprecedented show of grief from the public, when people left flowers at her former home in Kensington Palace in London in 1997. Twenty years on, many still do.

And some may even go against the wishes of family and friends.

Flags and flowers were left outside the Royal Artillery barracks where Lee Rigby was killed

A caretaker was recently met with death threats when he removed parts of a memorial to murdered soldier Lee Rigby, near where he was killed in Woolwich, south-east London.

Greenwich Council said far-right groups were using the memorial "for their own causes" - and in January had threatened council workers for "going about their job".

The council said it would leave flowers on the railings near to where Fusilier Rigby was killed, but that flags had been put up against the family's wishes.

A very British memorial

The practice of making small street shrines became commonplace during the First World War, with the first set up in Hackney in 1916.

The movement spread throughout the country after Queen Mary visited the East End shrines.

Most World War One casualties were buried overseas, so street shrines across Britain became common

But Britons are still relatively restrained compared with the rest of Europe, says roadside memorial expert Geraldine Excell, of Reading University.

In Mediterranean countries, family and friends may leave a miniature church where someone has died in a tragic accident - known in Greek as "Kandilakia".

"I've met a family in Crete who travel over 15 miles every night to light a candle at their son's roadside memorial," she says.

But she says the practice seems to be growing in the UK.

"There isn't any sign of it diminishing," she says. "Sadly there seem to be more and more on our streets."

- Published12 April 2018

- Published22 July 2013

- Published21 October 2014