Windrush: Who exactly was on board?

- Published

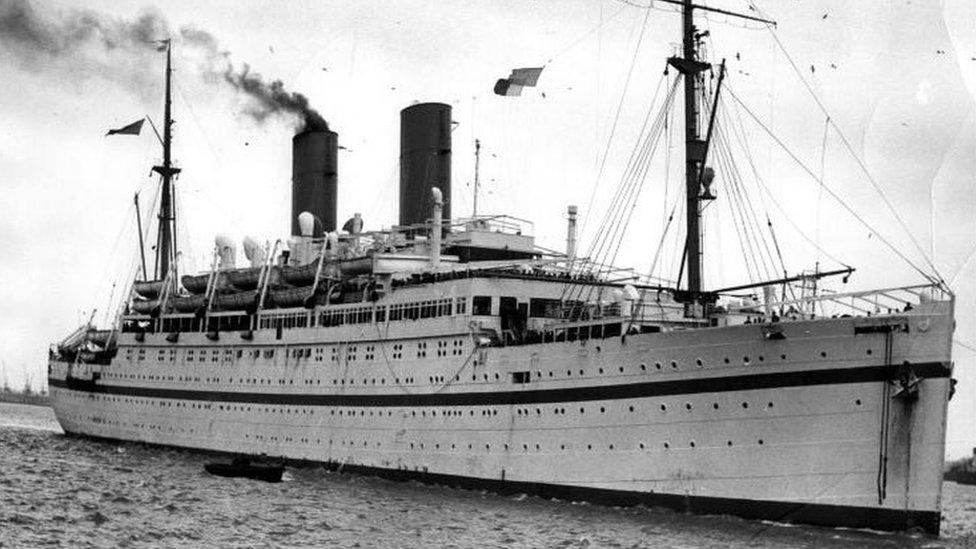

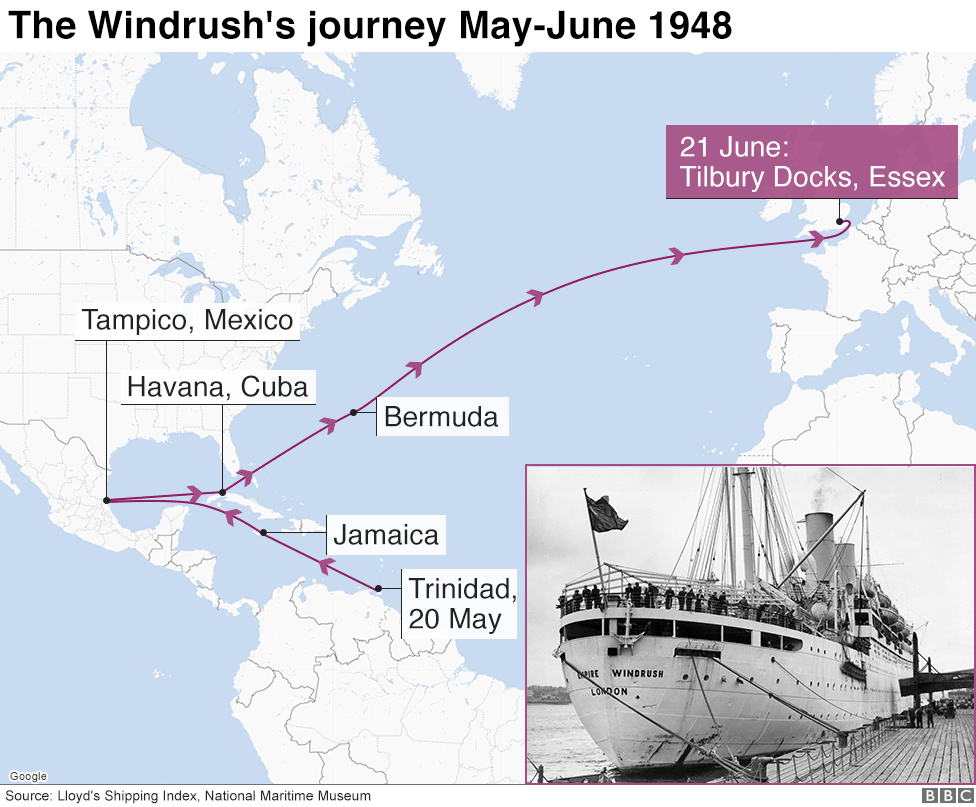

The British troopship HMT Empire Windrush anchored at Tilbury Docks, Essex, on 21 June 1948 carrying hundreds of passengers from the Caribbean hoping for a new life in Britain - alongside hundreds from elsewhere. Who were they?

June 2020: To mark this year's Windrush Day, on 22 June, we have retrieved this article from our archives.

The former passenger liner's journey up the Thames on that misty June day is now regarded as the symbolic starting point of a wave of Caribbean migration between 1948 and 1971 known as the "Windrush generation".

Many were enticed to cross the Atlantic by job opportunities amid the UK's post-war labour shortage.

But, despite living and working in the UK for decades, it emerged last year that some of the families of these Windrush migrants have been threatened with deportation, denied access to NHS treatment, benefits and pensions and stripped of their jobs. The UK government was forced to apologise and offered compensation for anyone who had "suffered loss".

Who was on board the Windrush in 1948?

The ship - which dropped anchor on 21 June and released its travellers a day later - was carrying 1,027 passengers, including two stowaways, according to BBC analysis of the ship's records kept by the National Archives., external

Alongside those travelling from the Caribbean for work, there were also Polish nationals displaced by World War Two, members of the RAF and people from Britain.

Passenger Lucile Harris, who settled in Britain from the Caribbean, recalled her arrival in Tilbury in an interview with the BBC in 1998 to mark the 50th anniversary of the Windrush sailing.

"It was a lovely day, beautiful, and they [family] were all at the dock waiting for me... I was very excited."

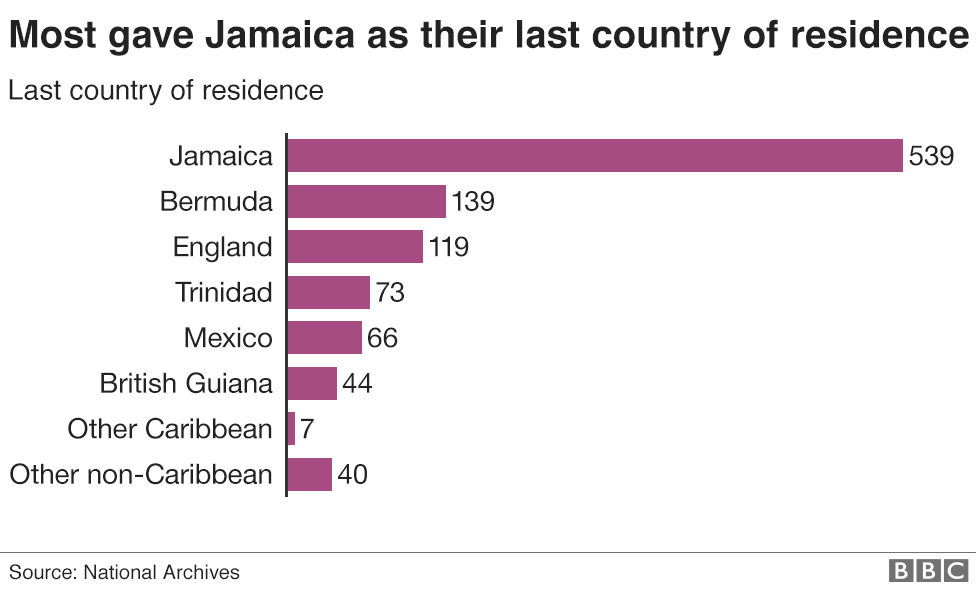

According to the ship's passenger lists, more than half of the 1,027 listed official passengers on board (539) gave their last country of residence as Jamaica, while 139 said Bermuda and 119 stated England. There were also people from Mexico, Scotland, Gibraltar, Burma and Wales.

According to Nicholas Boston of the City University of New York, those who gave Mexico as their last country of residence were a group of Polish refugees, external - mainly women and children - who had been offered permanent residence in Britain.

Overall, 802 passengers gave their last country of residence as somewhere in the Caribbean.

Many of them had paid £28 (about £1,000 today) to travel to Britain in response to job adverts in local newspapers.

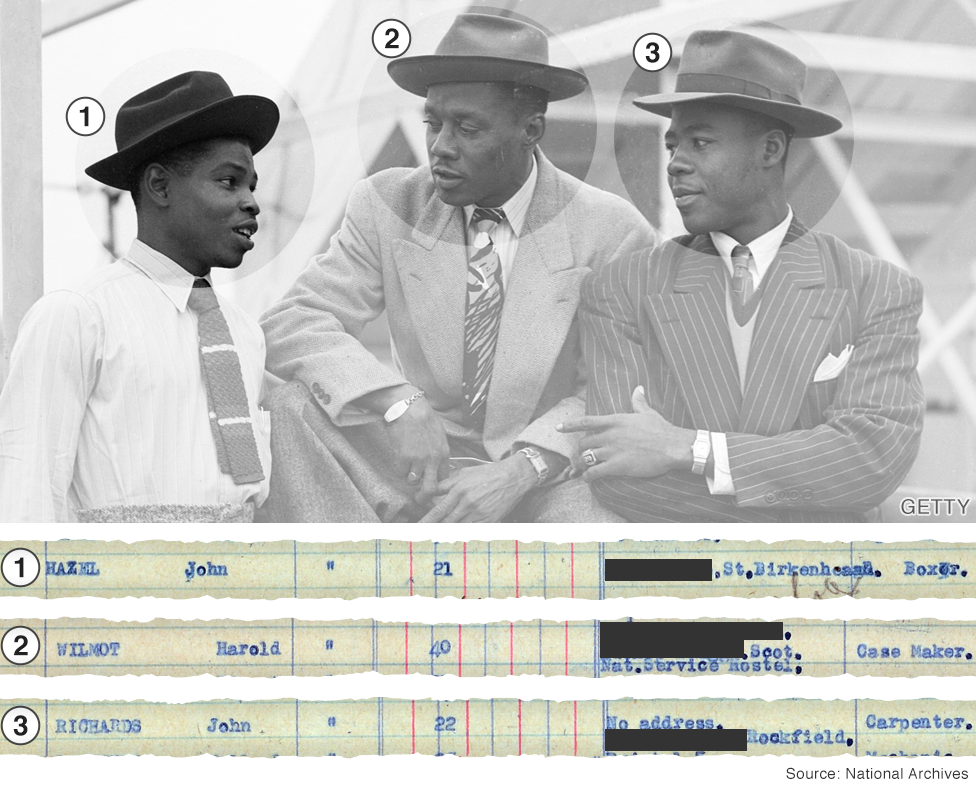

Among them were John Hazel, 21, a boxer, Harold Wilmot, 32, a case maker and John Richards, 22, a carpenter, seen here in a photograph taken on arrival - alongside their records from the National Archives passenger list.

Mr Richards, interviewed by the BBC in 1998, was, like many others, shocked to discover the difference between the "mother country" he had seen in books and the reality he was confronted with.

"I know a lot about Britain from school days but it was a different picture from that one, when you came face to face with the facts. It was two different things," he said.

"They tell you it is the 'mother country', you're all welcome, you all British. When you come here you realise you're a foreigner and that's all there is to it."

According to the ship's records, most of the Windrush's passengers got on in Jamaica, but others also joined the vessel in Trinidad, Tampico and Bermuda.

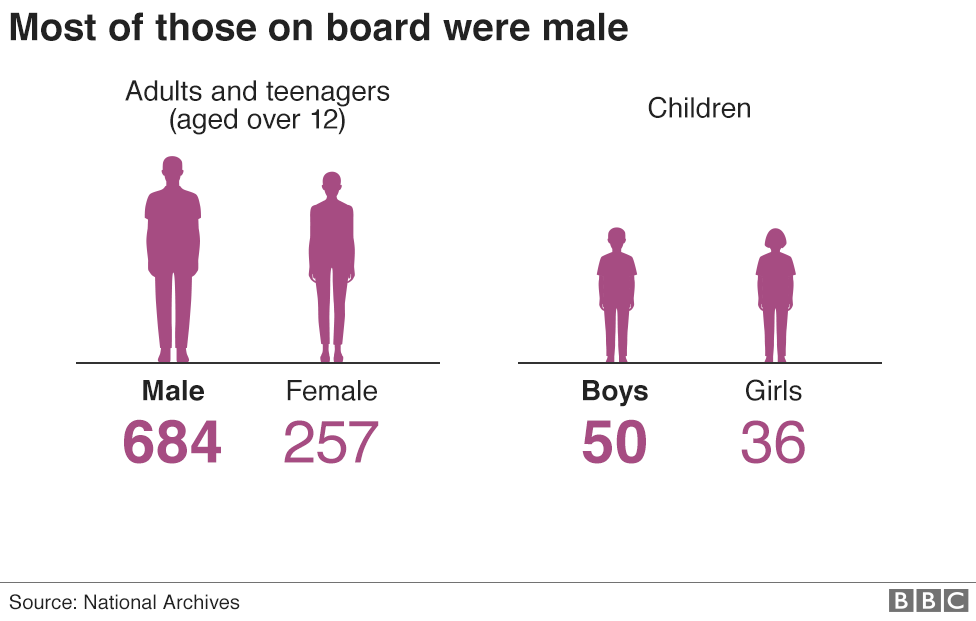

As many of the eyewitness accounts have stated since, the majority of the people on board were men. There were 684 males over the age of 12, alongside 257 females of the same age. There were also 86 children aged 12 and under.

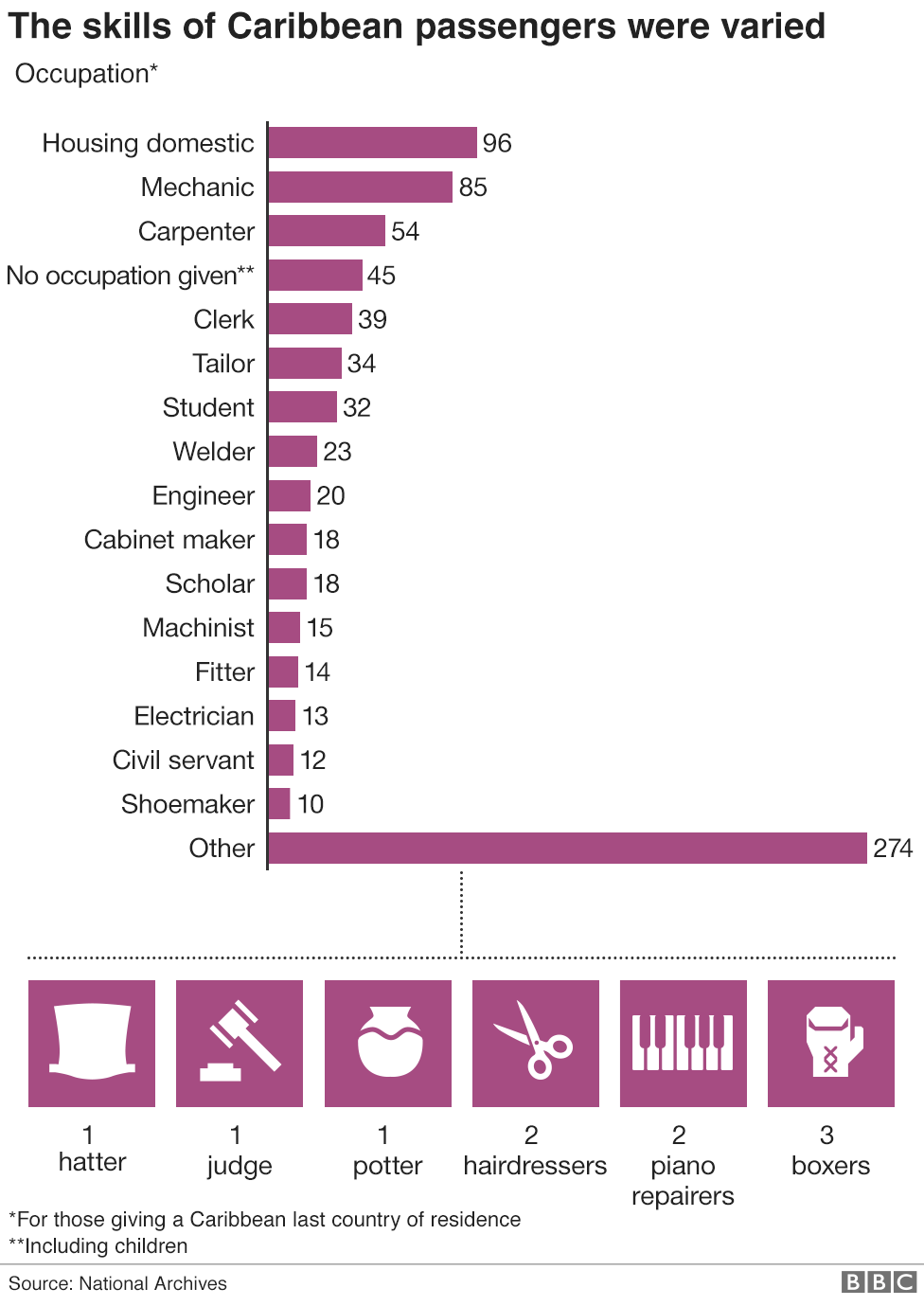

The listed occupations on the passenger lists give some indication of the wide range of skills that were on offer. Among those arriving from the Caribbean were mechanics, carpenters, tailors, engineers, welders and musicians.

According to the RAF, dozens of the Caribbean passengers were also RAF airmen, external returning from leave or veterans re-joining the service. A future Mayor of Southwark, Sam King, who had served in England with the wartime RAF, was among them.

Also among the Caribbean passengers was a hatter, a retired judge, a potter, a barrister, two hairdressers, two actresses, two piano repairers, two missionaries, three boxers, five artists and six painters.

The most noted occupation, though, was "HD" - or "housing domestic" - meaning a housewife, servant or cleaner. There were 172 overall on board - 96 from the Caribbean.

Among the boxing hopefuls on board were Charles Smith, 21, a welder and boxer, Vernon "Boy" Solas, 18, mechanic and boxer, and boxing manager Mortimer Martin, 31, who was also a welder, captured in this photograph on arrival.

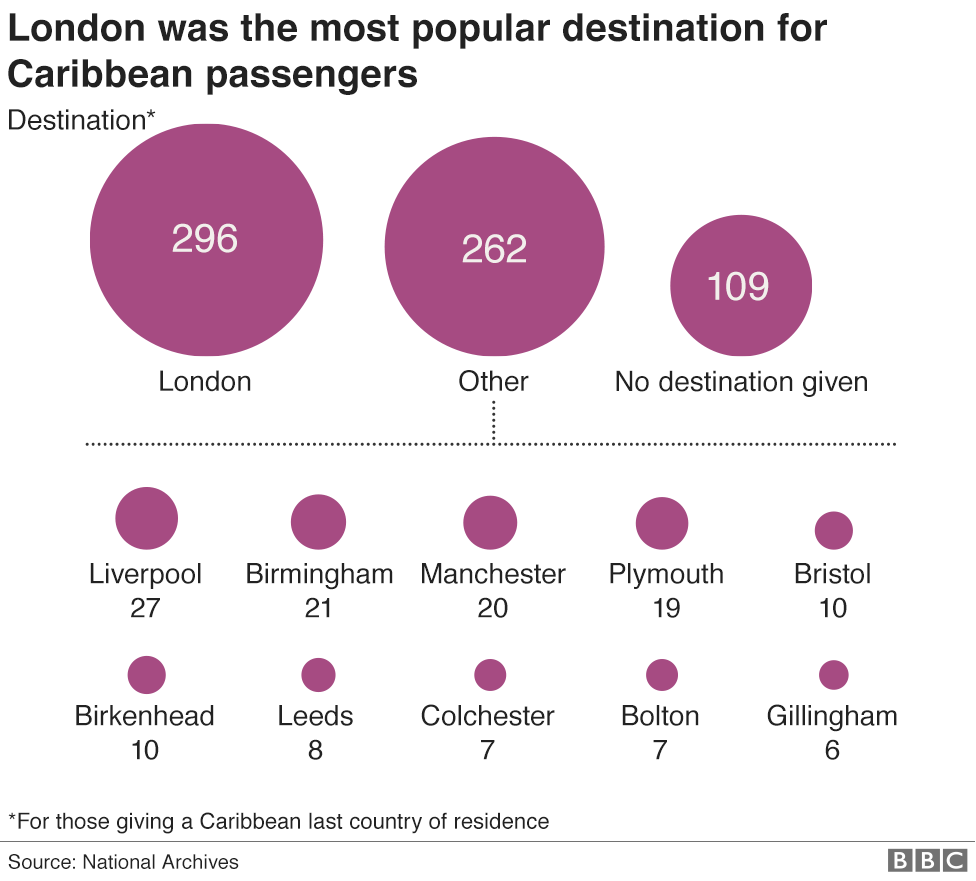

Perhaps unsurprisingly, the most popular destination recorded by passengers from the Caribbean was London - 296 people gave the city as their planned place of residence.

Interestingly, 109 passengers didn't give any address, perhaps indicating they had no fixed plan on arrival.

A number of other passengers planned to go to Liverpool, Birmingham, Manchester and Plymouth.

Those that had nowhere to stay were temporarily housed in a former air raid shelter at Clapham South underground station.

Newspaper reports from the time state how those at the shelter went on to find jobs through the nearest Labour Exchanges (Job Centres), one of which was in Coldharbour Lane, Brixton.

Many then moved into rented houses and rooms in the Brixton and Clapham areas, working for employers such as the National Health Service or London Transport.

From here, large Caribbean communities developed, contributing to the political, social and musical life of Britain ever since.

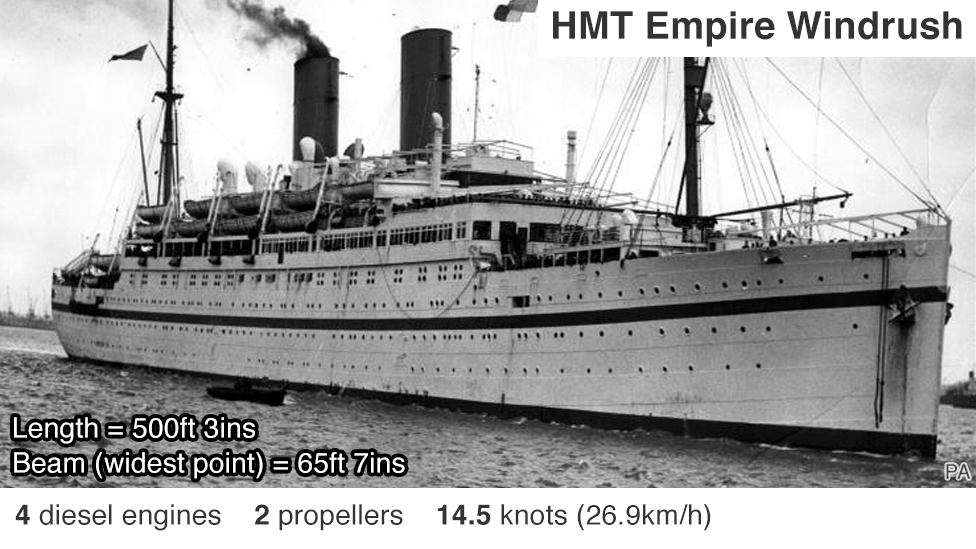

What was the Windrush like?

The ship - full name HMT Empire Windrush - was originally a German passenger liner given to the UK as war reparation in 1945.

First called Monte Rosa, it was converted to a troopship and renamed HMT Empire Windrush in 1947.

What was life like on-board the Windrush?

Oswald "Columbus" Denniston, who was the first of the Windrush passengers to get a job according to the Daily Express at the time, told the BBC in 1998 that the atmosphere on the ship was "jolly"., external

"We had two or three bands - calypso singers. And Jamaican people are happy-go-lucky people. When you have more than six you have a party."

On leaving the ship on 22 June, the then 35-year-old began work the same day handing out rations at the shelter in Clapham where the Windrush passengers were staying.

Mr Denniston, who died in 2000 aged 86, went on to settle in Brixton, where he worked as a street trader.

"Many of us thought we would come here to get a better education and to stay for about five years," he said. "But then some of us have ended staying for 50."

As for the ship itself, it made its final voyage in 1954, catching fire and sinking in the Mediterranean Sea with the loss of four members of crew. All of its passengers were saved.

This article was first published on 27 April 2018

- Published20 April 2018

- Published18 April 2018