Advice for the Windrush generation on what to do next

- Published

Many Windrush migrants who have had their legal status called into question now have questions of their own for which they are seeking answers.

Adam Sinfield is a Bristol-based lawyer who has previously worked for the UK Border Agency as a case worker and presenting officer. He specialises in immigration law and is a member of the Immigration Law Practitioners' Association.

After contacting the BBC, he agreed to answer some of the questions we had received from those affected by the Windrush immigration row. The answers are designed to help people understand some of the common issues and should not be considered as legal advice.

How can I have been born and raised here but still not be classed as a British citizen?

Katrice Louis's mother came to the UK from St Lucia as an eight-year-old in 1967 and has been resident in the UK ever since. Katrice is 18, born in west London and has lived in the UK all her life.

Both only discovered they are not British citizens when they tried to renew their passports in 2005 for a family holiday.

Because of changes in immigration law, the family has the unusual situation where Katrice's older siblings have citizenship and passports but she does not.

Explained: What is the 'hostile environment' policy?

Adam says: "Being born in the UK does not automatically confer citizenship, especially if you were born on or after 1 January 1983.

"British nationality law is incredibly complex and your nationality may depend on the status of your parents at the time of your birth, their country of origin and Commonwealth connections and many other factors."

How do we move forwards if we don't have the documents on which we travelled to the UK?

Alison Ebanks' father can't find the original document on which he travelled to the UK. He came with his brothers as an adult and travelled on a British passport in the early 1960s.

Alison's mother has a British passport and leave to remain.

Alison Ebanks' parents

Her father was issued with a temporary document in 2012 to travel to Jamaica, but when he tried to travel for his sister's funeral in 2014 he was warned he might not be allowed into the UK on his return.

Adam says: "Home Office policy allows for discretion in the consideration of applications and whilst such evidence would be very useful, it is not necessarily essential.

"Further, whilst you may not have the document to confirm your actual arrival date, you may be able to seek alternative evidence which confirms your presence in the UK prior to 1 January 1973, such as school, work or medical records.

"The Home Office may, and at their discretion, also be able to make checks with their own records or other government agencies. In light of this scandal, the Home Secretary has announced they will seek to be more flexible in undertaking their own checks."

Would I have a case to claim for loss of earnings?

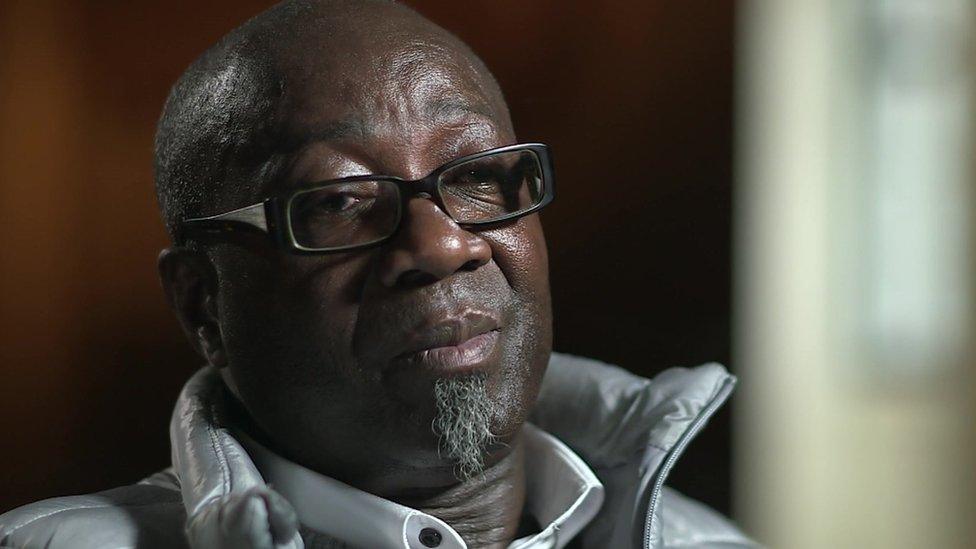

Nick Broderick came to the UK as a baby with his mother, who travelled from pre-independence Jamaica on a British passport in 1962.

He has been fighting for four years to prove his legal status, during which time there were periods where he was unable to work because of the restrictions placed on him.

Windrush migrant Nick Broderick: 'I contemplated suicide'

Adam says: "I am not really able to answer this.

"I do not believe so, as there is no contract between the state and its subjects, but this would be more against an employer for possible unfair dismissal.

"Unfortunately, I also doubt this as the Home Office's position is likely to be that anyone in this circumstance is legal, they just cannot prove it.

"As such, they could have applied for confirmation of their lawful status any time from 1973 to the present day."

I want to get on with my life - can I get this whole thing fast-tracked?

Whitfield Francis was born in Jamaica in 1958 and came to England with his parents at the age of nine.

He only realised there was an issue over his right to remain in the UK when he tried to change jobs four years ago and was unable to provide proof of his status - something he did not have - and he has not been able to work since.

Whitfield Francis - here with his eldest daughter Maria - came to England with his parents at the age of nine

Adam says: "Yes, but at a cost. Instead of applying by post, you may apply at a Premium Services Centre in person for a same-day decision. However, there is an additional fee of £610 to use this service, in addition to the £229 application fee.

"You must book an appointment, which may take some time, at one of the eight locations, external - Belfast, Cardiff, Croydon, Glasgow, Liverpool, London, Sheffield and Solihull.

"However, there is no guarantee the application will be decided the same day. If the caseworker believes your case is complex, which may certainly occur in these circumstances, your application will not be decided straight away but will be posted to a case-working team.

"Your case will still be prioritised, but may then take several weeks, or even months."

The Home Office has announced a dedicated team "aims to resolve all cases within two weeks of all of the information being pulled together"., external

Can I get this biometric card, and does it give me citizenship?

Whitfield added that he can't afford to pay for a biometric residence permit or for legal assistance.

Adam says: "If you arrived before 1973, and can show you have not lost your status (through two or more years' absence or criminality), you will be able to obtain a Biometric Residence Permit confirming there is no time limit on your stay.

"However, settlement/indefinite leave to remain is not the same as citizenship.

"If you have held indefinite leave to remain for over 12 months, and have lived legally in the UK for over five years, or three if you are married to a British citizen, and can meet the life and language requirements, amongst other requirements, you should be able to apply to become British.

"This will cost you £1,330 for the application, and the fee is retained if the application is refused."

Produced by: Alex Murray, Georgina Rannard, Bernadette McCague and Helen Dafedjaiye, from the UGC and Social News team

- Published19 April 2018

- Published18 April 2018

- Published17 April 2018

- Published17 April 2018