Windrush generation: Theresa May apologises to Caribbean leaders

- Published

Theresa May's Windrush apology to Caribbean leaders

Prime Minister Theresa May has apologised to Caribbean leaders over the Windrush generation controversy, at a Downing Street meeting.

She said she was "genuinely sorry" about the anxiety caused by the Home Office threatening the children of Commonwealth citizens with deportation.

The UK government "valued" the contribution they had made, she said, and they had a right to stay in the UK.

It comes amid reports some are still facing deportation.

The deportation of one man, which had been due to take place on Wednesday, has been halted following an intervention by Labour MP David Lammy.

The Tottenham MP said the mother of 35-year-old Mozi Haynes got in touch saying her son was due to be removed from the country after two failed applications to stay.

Mr Lammy later tweeted that he had been contacted by Immigration Minister Caroline Nokes, who had said that Mr Haynes would not now be deported on Wednesday and his case was "being reviewed".

The Tottenham MP, who has called the controversy a "national disgrace," urged the children of the Windrush generation facing deportation to contact him, promising "justice will be done".

Mr Lammy said that of 12,056 deportations in 2015, 901 were over 50 years of age. and 303 were to Jamaica. He is calling on the Home Office to review all such cases since 2014 to "ensure no wrongful detentions have taken place".

The Home Office said it was making efforts to speak to Mr Haynes to advise him that there is no requirement for him to leave the UK. Officials say it is not a Windrush case and was never an "enforced removal".

The department said it was looking at 49 cases relating to Windrush migrants as a result of calls received on Tuesday.

Landing cards

A former Home Office employee has, meanwhile, told The Guardian, external that thousands of landing card slips recording Windrush immigrants' arrival dates in the UK were destroyed in 2010 during an office move.

The former worker, who is not named by the newspaper, said managers were warned by staff that destroying the cards would make it harder to check the records of older Caribbean-born residents experiencing difficulties proving their right to remain in the UK.

The government said the decision to "dispose of" the cards had been an "operational" one, taken by officials at the UK Border Agency, rather than the then Home Secretary Theresa May.

A Home Office spokesman said: "Registration slips provided details of an individual's date of entry, they did not provide any reliable evidence relating to ongoing residence in the UK or their immigration status.

"So it would be misleading and inaccurate to suggest that registration slips would therefore have a bearing on immigration cases whereby Commonwealth citizens are proving residency in the UK."

The prime minister's spokesman said things like school records, exam certificates, employment records and bills were seen by the Home Office as "more reliable evidence of ongoing residence".

In her apology to Caribbean leaders, Theresa May said she wanted to "dispel any impression that my government is in some sense clamping down on Commonwealth citizens, particularly those from the Caribbean who have built a life here".

She said the current controversy had arisen because of new rules, introduced by her as home secretary, designed to make sure only those with the right to remain in the UK could access the welfare system and the NHS.

"This has resulted in some people, through no fault of their own, now needing to be able to evidence their immigration status," she told the foreign ministers and leaders of 12 Caribbean nations in Downing Street.

"And the overwhelming majority of the Windrush generation do have the documents that they need, but we are working hard to help those who do not."

A look back at life when the Windrush generation arrived in the UK

The PM added: "Those who arrived from the Caribbean before 1973 and lived here permanently without significant periods of time away in the last 30 years have the right to remain in the UK.

"As do the vast majority of long-term residents who arrived later, and I don't want anybody to be in any doubt about their right to remain here in the United Kingdom."

A new taskforce and helpline has been established for those people who arrived from the Commonwealth decades ago as children but were now being incorrectly identified as illegal immigrants.

Mrs May said people involved in the process of establishing their status should not be "left out of pocket" as a result and would not have to pay for documentation.

Cases have emerged - such as these in the Guardian, external - of people who have lost their jobs, rights to health and benefits and faced deportation despite being able to show they have paid tax and National Insurance for decades.

Jamaica's Prime Minister Andrew Holness said he had accepted Theresa May's apology, adding: "I believe that the right thing is being done at this time."

He said he did not know how many people had been affected by the controversy, but it was "at least" in the hundreds.

Asked if Mrs May was to blame for the situation, he said: "I can't answer that question. The truth is that she has said there has been a policy change, that this was an unintended consequence.

"As Caribbean leaders we have to accept that in good faith."

He added that Mrs May had not been able to say "definitively" that nobody had been deported as a result of issues with paperwork.

Andrew Holness said he had accepted Mrs May's apology

Timothy Harris, prime minister of St Kitts and Nevis, said: "We see this basically as the start of the dialogue, as evidence is uncovered which requires correction."

He said he hoped the British government would "make good any injustice" suffered by individuals, including by offering compensation.

Gaston Browne, the prime minister of Antigua and Barbuda, also backed compensation for those affected and told BBC News there should be "reprisals for those who dropped the ball" in the UK government.

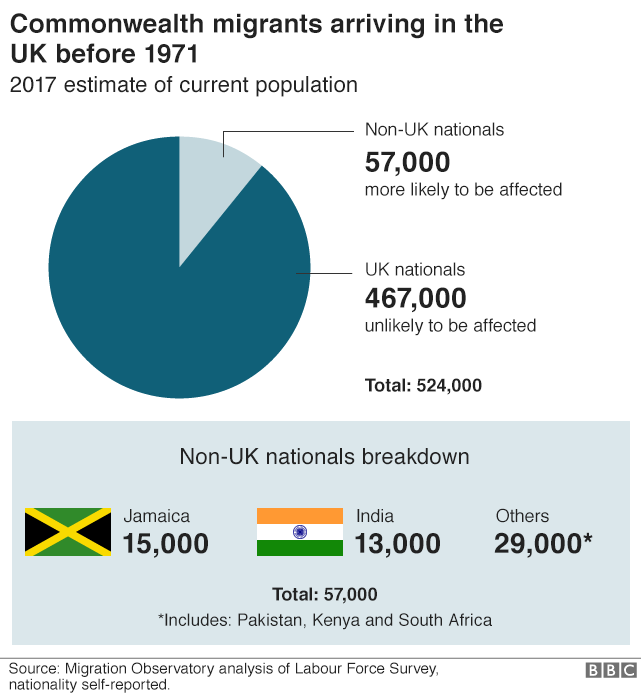

Thousands of people arrived in the UK as children in the first wave of Commonwealth immigration 70 years ago, often on their parents' passports.

They are known as the Windrush generation - a reference to the ship, the Empire Windrush, that brought workers from the West Indies to Britain in 1948.

Under the 1971 Immigration Act, all Commonwealth citizens already living in the UK were given indefinite leave to remain.

However, the Home Office did not keep a record of those granted leave to remain or issue any paperwork confirming it, meaning it is difficult for the individuals to now prove they are in the UK legally.

Changes to immigration law in 2012, which require people to have documentation to work, rent a property or access benefits, including healthcare, have highlighted the issue and left people fearful about their status.

Are you a member or descendant of the Windrush Generation - or did you arrive in the UK from another Commonwealth country as a minor between 1948-1971? We'd like to hear from you via email haveyoursay@bbc.co.uk, external.

Please include a contact number if you are willing to speak to a BBC journalist. You can also contact us in the following ways:

WhatsApp: +44 7555 173285

Send pictures/video to yourpics@bbc.co.uk, external

Tweet: @BBC_HaveYourSay, external

Text an SMS or MMS to 61124 (UK) or +44 7624 800 100 (international)

- Published16 April 2018

- Published16 April 2018

- Published11 April 2018

- Published13 April 2018