10 charts explaining the UK's immigration system

- Published

Immigration policy is about deciding who can come to the UK and what they can do while they are here.

But how exactly does this system work?

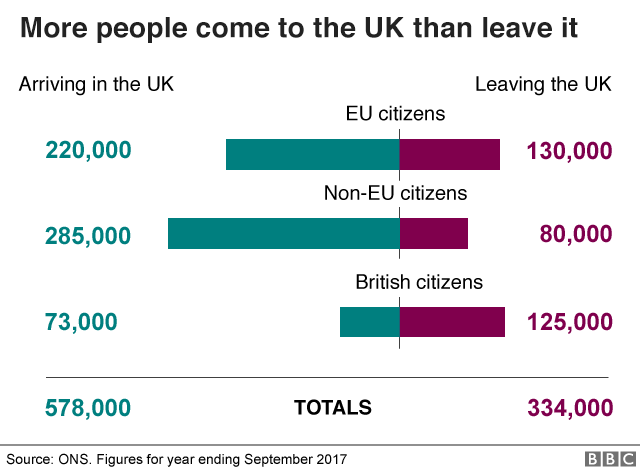

Net migration is the difference between the number of people arriving in the UK versus the number leaving, for at least 12 months.

This is what the government means when they talk about reducing net migration to the tens of thousands.

Although net migration is at its lowest point since early 2014, it still stands at 244,000.

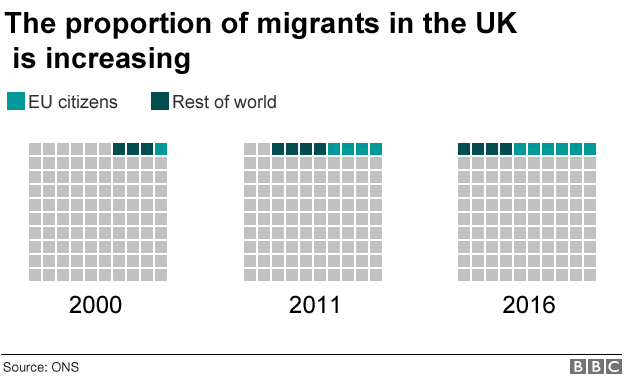

Migrants make up a bigger proportion of the UK population now than they did in 2000.

While non-EU nationals have remained a fairly stable percentage of the population as a whole, EU nationals are making up an increased proportion.

This is due to the freedom of movement rules between EU member states.

EU citizens are free to live and work in any of the bloc's 28 member states - set to fall to 27 when the UK leaves - without the need for a visa.

This is known as free movement of labour, one of the EU's four freedoms along with capital, goods and services.

There are some restrictions - after three months, EU migrants should prove that they are working, a student or have sufficient resources to support themselves without relying on the benefits system.

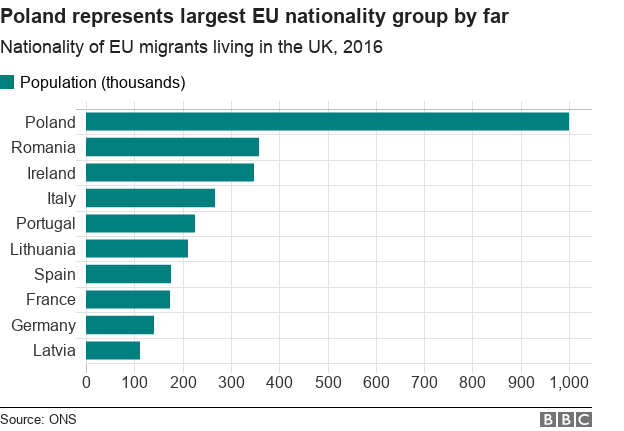

Although all EU nations take advantage of free movement, the greatest movers to the UK in recent years have been from Eastern European countries.

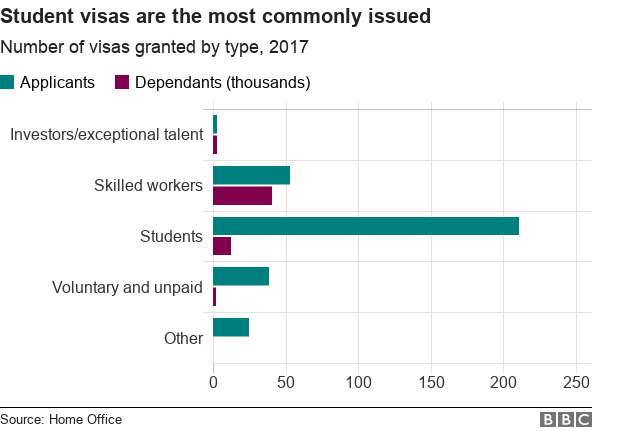

For those wanting to move to the UK from outside the EU, to work or study, there are different rules. You must apply for one of a number of visas.

These can range from Tier 1, preserved for investors and "exceptional talent", to Tier 5 visas for short-term voluntary and educational programmes.

The two most common are the Tier 2 skilled worker visas and Tier 4 student visas. Currently, no Tier 3 - unskilled labour - visas are being given out.

Some of these visas allow you to apply to bring dependants such as children and partners.

Visas work on a points-based system.

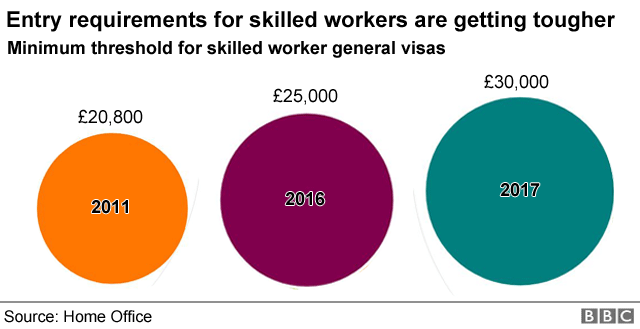

The criteria for these visas has got tougher in recent years.

For example, for a Tier2 "experienced skilled worker" visa, you now need to be paid at least £30,000 to apply, up almost £10,000 from 2011. You get more points for higher salaries or if your job is on the list of shortage occupations.

The number of these Tier 2 visas handed out is currently capped at 20,700 per year.

Most visas come with other conditions, including a knowledge of English, the need for a sponsor and agreeing not to claim benefits for a period of time.

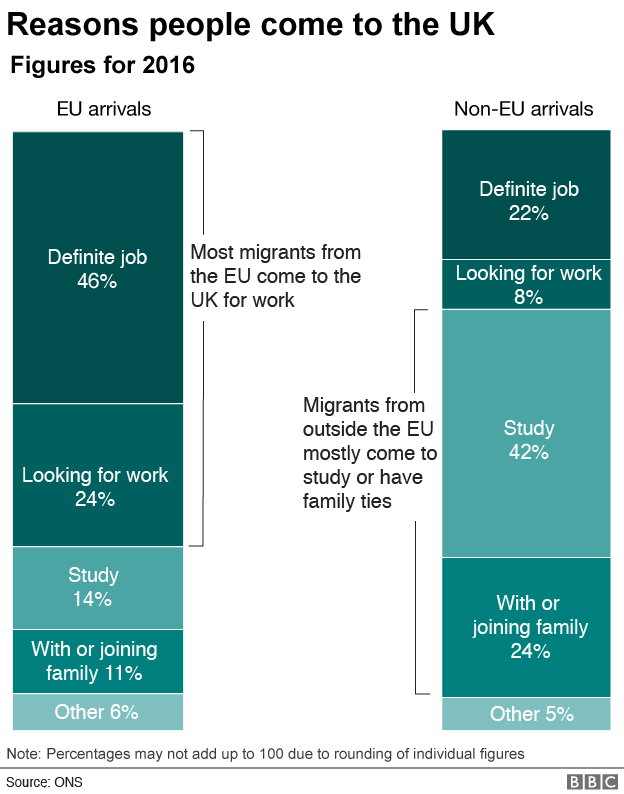

The different rules for EU and non-EU migrants mean their reasons for moving to the UK are considerably different.

For people who want to claim asylum, they must first reach the UK.

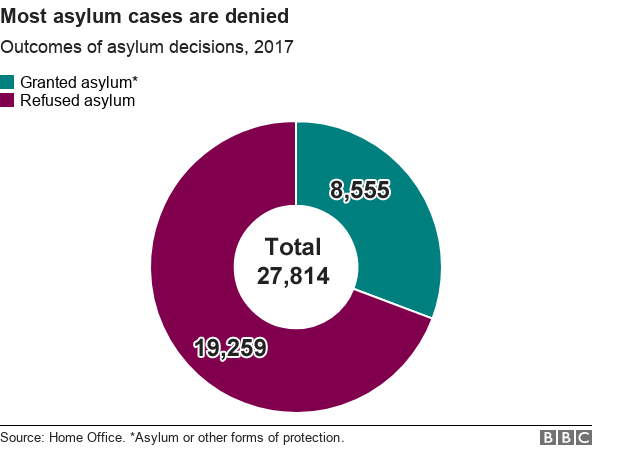

Once they have claimed asylum, they are given housing and financial support by the government until their application is dealt with. After that they might be granted refugee status, allowed to stay for other reasons or sent home.

If an applicant or their dependant is denied asylum, they can appeal against the decision.

There is usually a high rate of success in these appeals - in 2017, there were 17,390 asylum appeals heard in a lower asylum tribunal, of which 6,854 were successful.

The UK has also committed to taking in 20,000 Syrian refugees by 2020 as part of the international humanitarian effort.

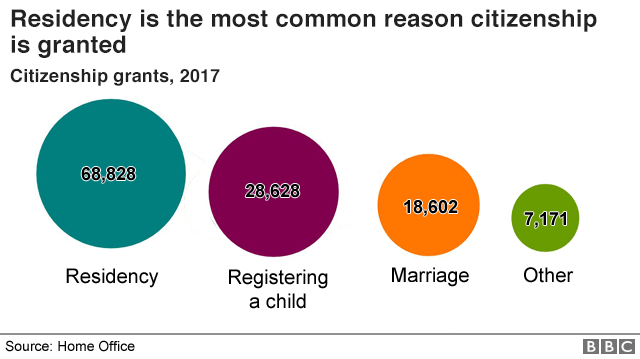

If you have been in the UK for at least five years without living elsewhere, you can apply for British citizenship.

To do so, you need to pass English language and Life in the UK tests and be of "good character".

In 2016, the majority of people granted British citizenship came from two areas: sub-Saharan Africa and South Asia.

People who breach the terms of their entry visas (or simply overstay as tourists), are breaking the law.

It is not entirely clear how many illegal immigrants there are in the UK, although estimates range from 300,000 to over a million.

Although tough rules have been gradually introduced under successive governments, the "hostile environment" policy of 2012 bolstered attempts to make life in the UK more difficult for illegal immigrants. This has included reducing ability to access work, healthcare and housing.

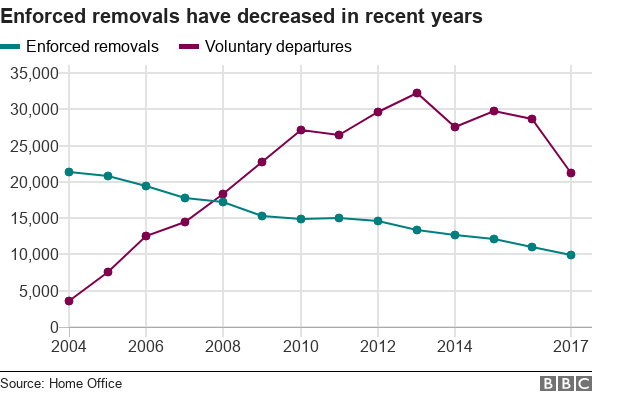

Enforced removals refers to those who are physically removed from the country.

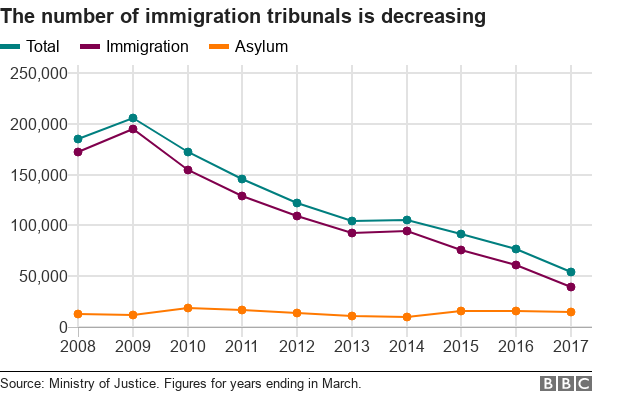

If someone disagrees with a decision made by the Home Office they can take it to an immigration and asylum tribunal.

In 2012, legal aid was removed for many immigration cases, and there has been a recent decrease in cases heard.

In 2017, 53% of the total claims ruled on were rejected. This increases to 60% when just taking into account asylum tribunals.

People might go to an immigration tribunal for a number of reasons, including breaches of freedom of movement, human rights and issues relating to family.

- Published22 February 2018

- Published7 March 2018