Brexit: What can UK learn from other external EU borders?

- Published

Technology can streamline EU borders but they are not frictionless.

As the British government continues to debate the kind of customs relationship it wants with the European Union after Brexit, one question looms large: how will it solve the Irish border problem?

One of the most difficult issues in the entire Brexit process is how to ensure that there is no return to a hard border between Northern Ireland and the Irish Republic, once that border becomes the external border of the European Union, of its single market and its customs union.

That is what has been promised: no physical infrastructure or checks of any kind at the border.

An open border is a vital part of the 1998 Good Friday Agreement which underpins the Northern Ireland peace process.

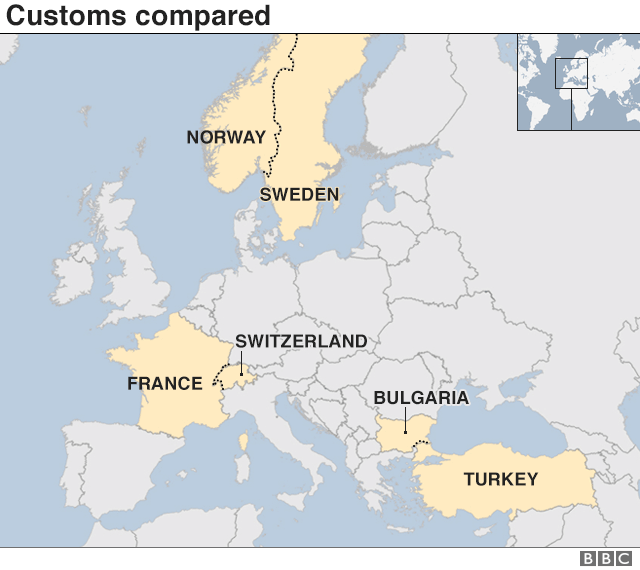

So, what can we learn from other external EU borders around Europe?

Norway-Sweden

WATCH: How tech helps Norway police its border

First of all let's head north - to the border between Norway and Sweden.

Sweden is in the EU, Norway isn't.

Norway is part of the single market through its membership of the European Economic Area (EEA) but it's not in the customs union.

Being in the single market means Norway respects the EU's four freedoms - the freedom of movement of goods, services, capital and people. But that doesn't get rid of the need for customs checks.

Even so, Norway's border with Sweden is one of the simplest and most technologically advanced customs borders in the world, and lorries only ever have to stop once. They do not have to repeat the same process on both sides of the border

Waiting to be processed by the Norwegian customs agents

At the main border crossing at Svinesund, Norwegian customs say they deal with about 1,300 heavy goods vehicles every day - which is less than a tenth of the number that passes through Dover.

And the average time from when a lorry arrives to when it leaves the border? About 20 minutes. That includes roughly 10 minutes waiting time, three to six minutes of handling time, and the time spent coming off the road to complete the customs process.

It is highly efficient, but certainly not entirely frictionless.

Turkey-Bulgaria

Lorries can be forced to wait more than 24 hours at busy times at the Turkey-Bulgaria border

Next - we go south - to the border between Turkey and Bulgaria.

Again Bulgaria is in the EU, and Turkey isn't. But Turkey does have a customs union with the EU for most manufactured goods.

Here though the delays are much longer. Outside the single market, there's a need for all sorts of documentation, from export licences and invoices to transport permits.

That means huge queues of lorries are normal, and they are made worse because there are only three road crossings open along the entire border. A report prepared for the European Commission in 2014 suggested a waiting time of about three hours for lorries travelling from Turkey to Bulgaria.

But drivers hoping to cross the border say they often have to wait for more than 24 hours at busy times.

So being in a customs union doesn't automatically make border checks entering or leaving EU territory disappear; in this case that's partly because Turkey is not part of the single market and its common set of rules and regulations.

Switzerland-France

There are also external EU borders in the heart of Europe, such as the one between Switzerland and France.

France, of course, is a founder EU member, while Switzerland is not in the EU but is part of the single market thanks to a series of bilateral agreements.

Again, though, Switzerland is not in the customs union.

The Swiss border is often held up as an example of what could be achieved in Ireland, but here too there is physical infrastructure at all the main crossings - it is a hard border.

According to information from the International Road Transport Union (IRU), the average waiting time for lorries carrying goods ranges from 20 minutes to more than two hours if full inspections have to be carried out.

Conservative MEP and Brexiteer Daniel Hannan's claim about a "largely unmanned and invisible" Swiss border sparked a vigorous debate on social media.

Technology

In other words, technology is improving things, and streamlining customs procedures at borders - and it will do more of that in the years to come.

One of the two customs proposals being examined by the UK government argues that new technology and trusted trader schemes can keep border checks and infrastructure to a bare minimum.

But note the name of the proposal - maximum facilitation: it facilitates trade, it does not get rid of borders altogether.

That means that if the UK leaves all the EU's economic structures there is currently no example anywhere around Europe, or further afield, that can keep the Irish border after Brexit as open as it is now.

With less than a year to go until the UK is due to leave the EU, that is the acute political dilemma at the heart of the current debate.