The couple banned from staring through neighbours' windows

- Published

Sheila and Nigel Jacklin have been banned from looking through their neighbours' windows

Prosecutions for breaking Community Protection Notices - sometimes known as the new Anti-Social Behaviour Orders (Asbos) - are on the rise in England and Wales. But there are concerns the powers are being used unfairly, with no need to prove the accusations being made.

"I'm desperately sad that this has happened," Sheila Jacklin tells the BBC Victoria Derbyshire programme.

"I put on a brave face, because you have to. But I am deeply sad."

Sheila has lived with her husband Nigel in their home on the East Sussex coast for 26 years.

It was the idea of being moments from the beach that first attracted them to the area, Sheila says.

But taking their normal path to the seafront means they now risk breaking the law.

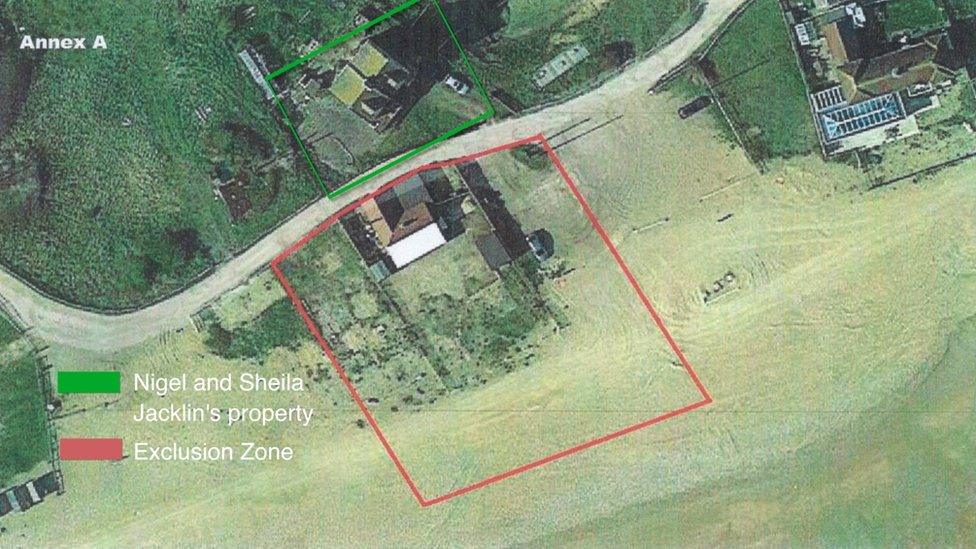

The CPN means Nigel and Sheila are not allowed to drive on the area in front of their house

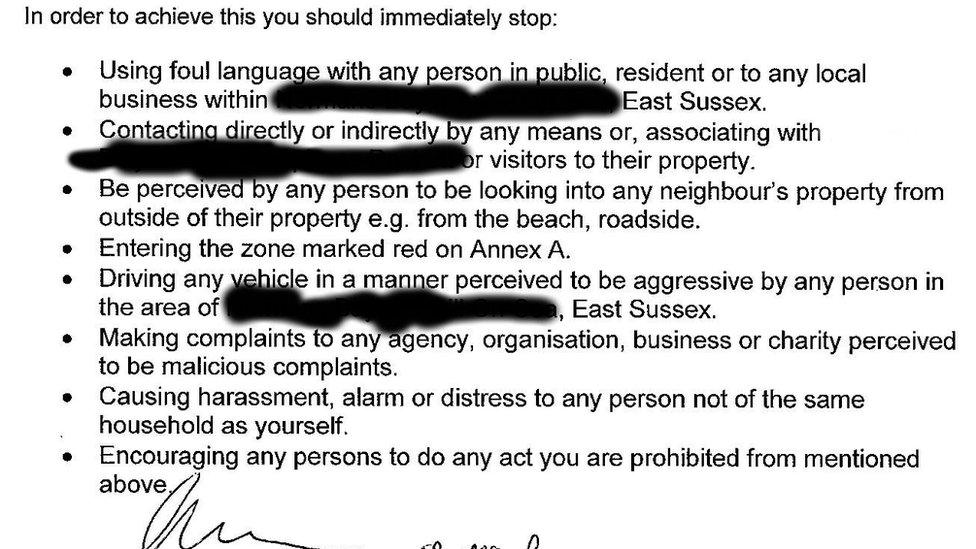

This is because the couple have been accused of "harassing" their neighbours, originating from a planning dispute, and been issued with a warning letter for a Community Protection Notice (CPN).

It means they are subject to a number of rules which, if broken, could see them given a full CPN - which it is a criminal offence to breach.

The couple are not allowed to walk in a large area in front of their house, be perceived to be looking at any windows in their village or walk on the beach in front of their house.

They deny the claims of harassment, and say the council has placed the restrictions on them without hearing their side.

CPNs are designed to prevent unreasonable behaviour that affects the local community's quality of life, and are the closest of new powers, external to Anti-Social Behaviour Orders (Asbos), which were replaced in 2015 in England and Wales.

But, unlike Asbos, the CPN warning letters can be issued by police and councils without proof of the claims being made, and without going through the courts.

A copy of the Jacklins' CPN warning letter

Sheila describes the CPN warning as "ridiculous".

"[The exclusion zone] looks as if someone's got a red crayon and gone round [an arbitrary area]. There's no logic to it."

Rother District Council said: "In this case, Sussex Police issued a warning letter on behalf of the council in an attempt to resolve a long-standing neighbourhood dispute."

The exclusion zone placed on Sheila and Nigel

The Jacklins say they continue to walk in the area in front of their home, breaking their warning, and are expecting to be given a full CPN - which they say they will challenge in court.

"We are just doing what we have been doing for 26 years, so we'll continue to [go there]," says Nigel, resolutely.

Breaking a CPN can lead to a fine, and and multiple breaches can result in prison.

In the year ending September 2017, there were more than 1,220 prosecutions for breaching CPNs, a Freedom of Information request to the Ministry of Justice has found.

This was a 42% rise on the previous 12 months, the Victoria Derbyshire programme has found, when there were 855 prosecutions - of which 75% were successful.

The full number of CPN warning letters issued each year is not known.

Shouting, crying, arguing

Josie Appleton from the Manifesto Club, which campaigns for civil liberties, has concerns over how CPNs are issued - and says they are "very hard to appeal".

"A CPN can literally be written on a form, and after that it's a crime for you to do what they say you do.

"I really think that councils are not in the position to be issuing these legal sanctions against people.

"It's a completely arbitrary power. And where you have arbitrary powers you have bad law enforcement."

Josie Appleton says CPNs are very hard to appeal against

The Victoria Derbyshire programme has seen evidence of people receiving CPNs for shouting, crying, arguing and feeding birds in the garden.

One case involved a woman in north-east England who says she was issued with a CPN after making noise while being subject to domestic violence.

Joanne, who is challenging her CPN conviction, said the notice - plus a fine - was pushed through her door.

She believes it originates from complaints from one neighbour.

"I'm not paying the fine," she says.

"I've got no previous convictions, I'm a hard-working law-abiding citizen. I don't know how it's happening."

Simon Blackburn says CPNs enable the authorities to protect the public

Simon Blackburn from the Local Government Association, however, argues that CPNs are a valuable tool for reducing anti-social behaviour.

"Local authorities aren't going around looking for problems," he says, "they're responding to issues - very serious issues, often - that are reported to them.

"And we have a duty to protect the public, and we take that duty very seriously."

He says people have the right to appeal to a magistrates' court within 21 days, and often a warning letter is "all that's required" to ensure a change in the recipient's behaviour.

A Home Office spokesperson said: "We are clear that Community Protection Orders should be used proportionately to tackle anti-social behaviour."

But for Sheila, it is a power that is needlessly turning aspects of their daily life into an offence.

"It's the criminalisation of us, frankly," she says.

Watch the BBC's Victoria Derbyshire programme on weekdays between 09:00 and 11:00 on BBC Two and the BBC News Channel.

- Published24 December 2017

- Published24 July 2017