Brexit: Why services matter in any deal

- Published

As Downing Street sets out details of a possible post-Brexit customs arrangement, one of the suggestions that has emerged about the government's plans for the UK's future economic relationship with the EU is that it may try - in effect - to stay in the single market for goods, but have a much looser relationship for services.

Even if the cabinet reaches agreement, that may well be a non-starter as a negotiating proposal: the EU has consistently taken an extremely dim view of any British attempt to, as it would see it, cherry-pick parts of single market membership.

But the economy is often, for statistical purposes, divided into goods and services.

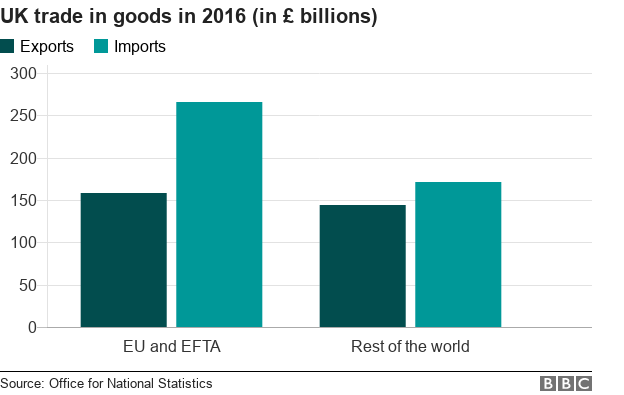

Data published by the Office for National Statistics, external shows that in 2016 the UK exported £157.8bn worth of goods to the EU and the four European Free Trade Association (EFTA) countries and imported £266.3bn.

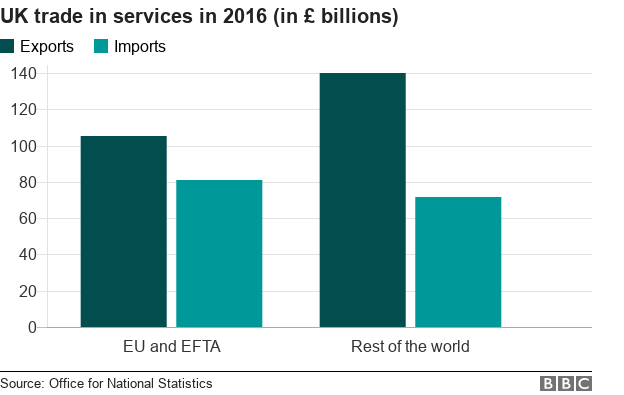

As for services, exports to the EU (plus EFTA) in 2016 were £105.5bn, while imports were worth £81.2bn.

It is one way to look at trade flows, but what data such as this does not reveal is that the relationship between goods and services is actually very complex.

Take a company like Rolls-Royce, external - one of the UK's largest manufacturing businesses. It is best known for making things like aircraft engines in particular (Rolls-Royce Motor Cars is now a wholly owned subsidiary of BMW).

But in 2017, while 48% of Rolls-Royce's revenue in civil aerospace was generated by what it calls original equipment (goods), 52% was generated by services.

A majority of the company's profit also comes from after-sales services such as long-term maintenance contracts on aircraft engines worldwide, rather than from the sale of the engines themselves.

More than half of Rolls-Royce's aerospace revenue was generated from services

Mission critical

In fact while it does make a profit on some engines, Rolls-Royce says it makes an average loss of £1.5m on each large civil aerospace engine it makes. In other words, this is a manufacturing business for which the supply of services is mission critical.

So in terms of the politics of Brexit, trying to divide British business neatly into those which deal in goods and those which deal in services isn't necessarily useful.

They are not mutually exclusive.

Many companies deal in both all the time and if the UK's trading relationship with the EU in goods was substantially different from its trading relationship in services, that could pose big challenges for some.

There are also a lot of UK-based service companies that are part of complex manufacturing supply chains.

They may provide technical or legal support, for example, to manufacturing firms in their local area and do no direct work themselves outside the UK.

But if the manufacturing firms they work with export to the EU, local service companies will also be vulnerable to any sudden change in the UK's trading relationships.

When, for example, the car company Jaguar Land Rover said it "urgently needs greater certainty" from the Brexit negotiations in order to "safeguard our suppliers, customers and 40,000 British-based employees", it was referring to suppliers of services as well as goods.

In fact if you add up all the small service companies around the country that are part of manufacturing supply chains of one kind or another, they make up a bigger slice of the UK economy than financial services in the City of London.

But they have much less influence, and usually receive far less attention in the Brexit debate.

- Published5 July 2018

- Published3 July 2018