Prisons: Why are they in such a state?

- Published

The government is taking over the running of Birmingham Prison after inspectors found "appalling" levels of squalor and violence.

But the problems experienced at Birmingham are not unique: many jails in England and Wales are struggling to maintain decent conditions and good order amid high levels of assaults, drug-taking and self-harm.

So why are prisons under pressure?

At Oakwood jail, near Wolverhampton, I met a man convicted of drug offences whom you could say is a "model" prisoner.

His name is Ben - his surname was withheld at the request of the prison. He is 42 and he acts as a mentor for other inmates, helping to sort out their problems and resolve tension and conflict.

"I feel like it's my way of giving back to society, paying my dues if you like," he told me. "But more importantly, it's because I want to do my time in a safe place."

A safe place. That's the priority for virtually all prisoners and prison staff. But judging from inspection reports, anecdote and statistics, many jails are far from safe.

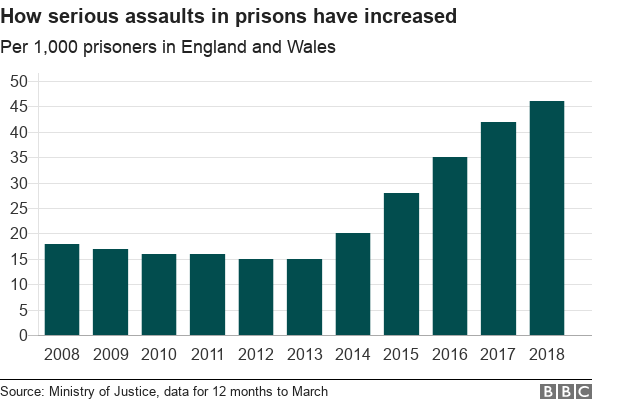

The surge in assaults tells only part of the story of violence in prisons.

In his annual report for 2017-18, external, Peter Clarke, the chief inspector of prisons, said the "ready availability" of drugs lay behind much of the violence.

That was what I found, too, during research for a BBC Radio 4 documentary.

The trade in drugs is co-ordinated by organised criminal networks operating from behind bars.

Prison provides a highly lucrative and, literally, captive market, particularly for synthetic substances, such as Spice. But it often leads to debt, threats, bullying and violence.

Spice, a former legal high, and other similar drug compounds are extremely unpredictable and known to cause health problems.

Their impact is only now becoming fully understood.

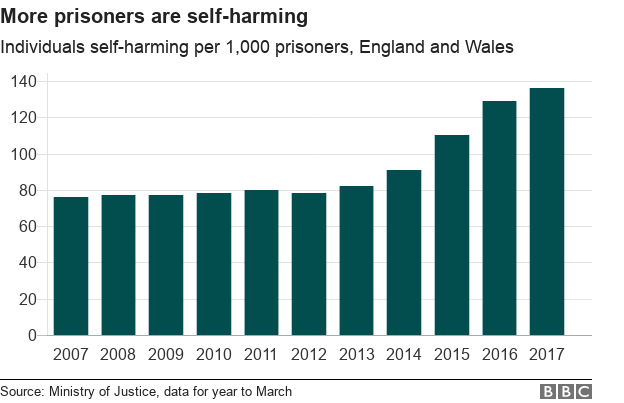

They're believed to have contributed to the rise in incidents of self-harm, though a clear causal link hasn't been established.

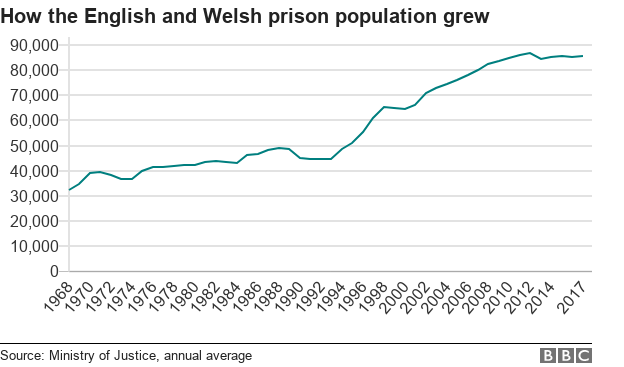

One of the principal pressures on the prison system is the number of people who are incarcerated.

Although the jail population in England and Wales - 83,064 - has fallen by more than 3,000 in the past 12 months, due to increased use of tagging and fewer people sentenced and remanded, it remains at historically high levels.

In 1991, there were 45,000 people locked up. Two decades later, there were 85,000.

Justice and policing are devolved matters for Scotland - where there has been nothing like the same long-term rise in the jail population - and Northern Ireland.

In Scotland the latest figure is around 7,500, the lowest it has been for a decade.

In Northern Ireland there are some 1,500 people in custody - slightly more than a decade ago, when the figure was around 1,300, but fewer than in the mid-1990s.

So why did numbers rise so steeply in England and Wales? Some lobby groups and criminologists point to a "moral panic" following the murder in 1993 of the toddler James Bulger.

Experts describe a sentencing "arms race" between political parties vying to be the strongest on law and order: former Conservative leader Michael Howard's "prison works" versus former Labour Prime Minister Tony Blair's "tough on crime, tough on the causes of crime".

Whatever the reason, the effect has been an increase in average sentence lengths, more offenders being jailed for life or indeterminate terms and tougher release conditions, so that prisoners are more likely to be sent back to custody for breaches.

New jails have been built, but have not kept up with demand. The Prison Reform Trust calculates that around 20,000 prisoners - almost a quarter of the total - are held in overcrowded conditions. Many share cells designed for one.

A report on Pentonville Prison said it was "overcrowded and crumbling"

Overcrowding has a corrosive effect. It is, in the words of Lord Woolf, the author of a report on the Strangeways prison riot that left two dead and almost 200 injured, "a cancer eating at the ability of the prison service" to deliver effective education, tackle offending behaviour and prepare prisoners for life on the outside.

Cost-cutting

When the coalition government came to power in 2010 it began to look for savings as part of its effort to reduce overall public spending.

Five years later the National Offender Management Service, which was then responsible for prisons in England and Wales, had its budget reduced by nearly a quarter.

Old jails that were expensive to operate were shut - 18 have closed since 2011.

But the other tactic in the efficiency drive has been a programme of "benchmarking".

Publicly run jails are required to peg their costs to the same level as the most efficient prisons, including those in the private sector.

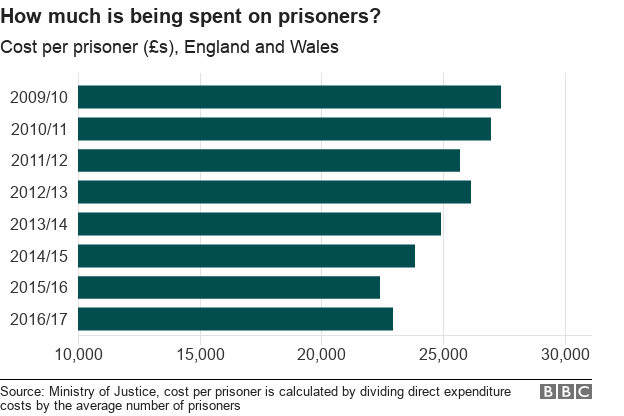

Fourteen jails in England and Wales, and two out of 15 prisons in Scotland, are operated by private firms - G4S, Serco and Sodexo - and benchmarking has certainly led to savings, with the average cost per inmate having fallen to around £23,000.

Benchmarking has also involved major changes to the regime in prisons and cuts to staffing.

A standardised "core day" has been introduced in some jails, with the aim of making the most of prisoners' time out of their cells and giving them certainty about what activities they are doing.

But the chief inspector of prisons said half of jails they inspected had too few programmes of useful activity. Two-fifths of the prisons were assessed as delivering "good" or "reasonably good" activities compared with more than two-thirds in 2009-10.

Wandsworth Prison, London

With the benchmarking programme and other cost-cutting, there was a dramatic reduction in staff numbers. Posts were cut in the Northern Ireland Prison Service, as well, but in Scotland staff numbers have risen.

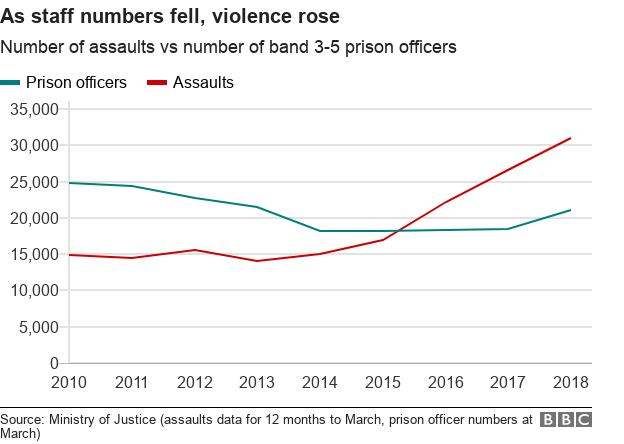

The overall number of staff employed across the public-sector prison estate in England and Wales fell from 45,000 in 2010 to just under 31,000 in September 2016.

Although a small part of the reduction was because of employees switching to jails transferred to the private sector, the decline was substantial by any measure, with the number of prison officers working in key front-line roles - bands 3-5 - down by more than 6,000.

That autumn in 2016, the then justice secretary, Liz Truss, persuaded the Treasury to invest in a recruitment drive. Since then, the number of front-line prison staff has gone up by 3,653, partially reversing the cuts that had been made. In June there were 21,608 - the highest number on the front line since January 2013.

The steep reduction in staffing, followed by a sharp rise, means the complexion of the workforce has changed. Prison officers with the skills and know-how of managing tricky situations, known as "jail-craft", have been lost, replaced by many young and inexperienced personnel: less than half have 10 or more years' service, while well over a third have worked behind bars for less than three years.

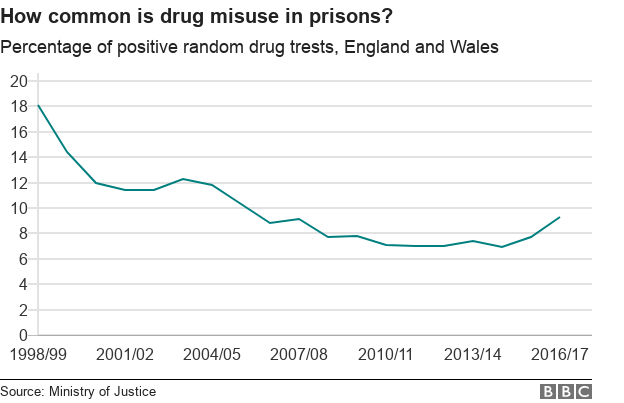

The departure of thousands of prison staff between 2010 and 2016 coincided with the arrival in prisons of Spice, and other former legal highs.

Initially, Spice and the other new psychoactive substances had the advantage for inmates of being almost impossible to detect in the random drug tests that take place on a regular basis in every establishment, though new screening methods have now been put in place.

The drugs have proved to be a game-changer in terms of prison stability. Inmates are able to arrange supplies by using mobile phones smuggled into jails - and there have been fewer staff to control the violence that's followed.

Briefing reporters when he launched his annual report in July, Peter Clarke said there was a "pretty obvious correlation" between a rise in violence and self-harm since 2013 and cuts to resources and staff, though he could not draw a "causative link".

He said: "It is noticeable that the huge increase in violence across the prison estate has really only taken place in the past five years, at the time when large reductions in staff numbers were taking effect."

The Ministry of Justice has now embarked on a programme to drive down levels of violence and drug-taking in jails: rehabilitation, education and training can't work in an institution where prisoners and staff are fearful and anxious.

Part of the department's approach, reducing the jail population to ease pressures on the system, is already taking effect, though David Gauke, the Justice Secretary, has indicated he'd like to go further, external.

He wants the courts to make more use of community sentences and send fewer offenders to jail for short spells, which lead to high rates of reoffending.

Over the summer, Rory Stewart, the Prisons Minister, said he would resign his post if assaults and drug-taking weren't substantially reduced within 12 months in 10 of Britain's worst-affected publicly run prisons in Yorkshire, Nottinghamshire and London.

It was a bold statement, followed within a few days by the announcement that the government was taking over the running of G4S-operated HMP Birmingham, external.

But Birmingham is just one of dozens of jails in trouble.

According to the Ministry of Justice, 39 are causing "concern" and the performance of a further 15 is of "serious concern", 13 of which are publicly run.

The ratings system is based on how well each facility is doing in three key areas: public protection; safety and order, and offender reform.

Prisons are under scrutiny like never before. A minister has staked his political career on cutting jail violence. The safety of tens of thousands of inmates and staff depends on it.