Who is Anjem Choudary and why was he in prison?

- Published

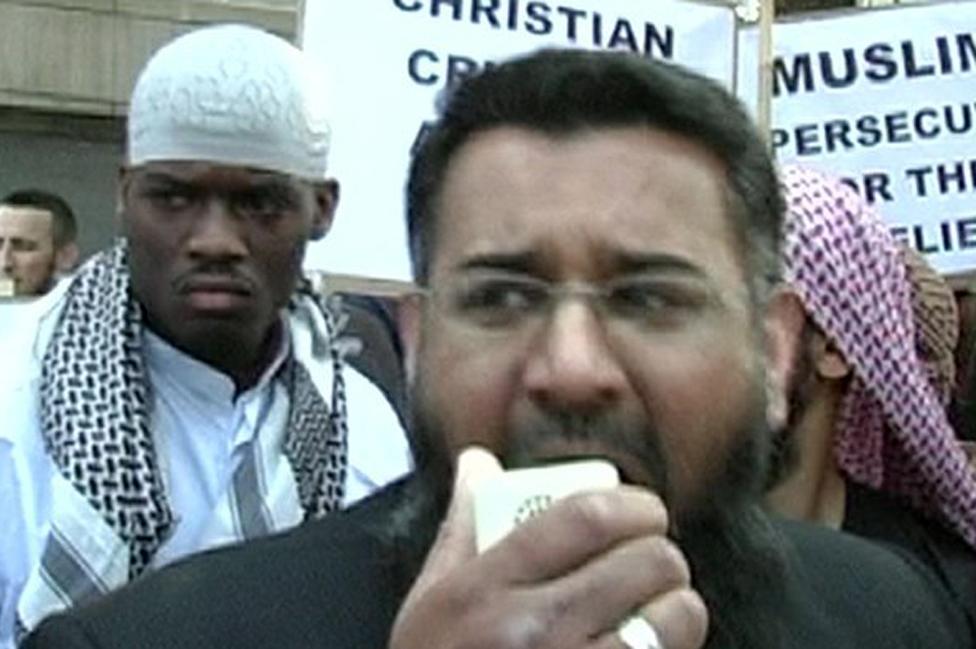

The poster behind Choudary at this April 2014 demonstration includes the words "Islamic State Is Solution" - the initial letters spell ISIS

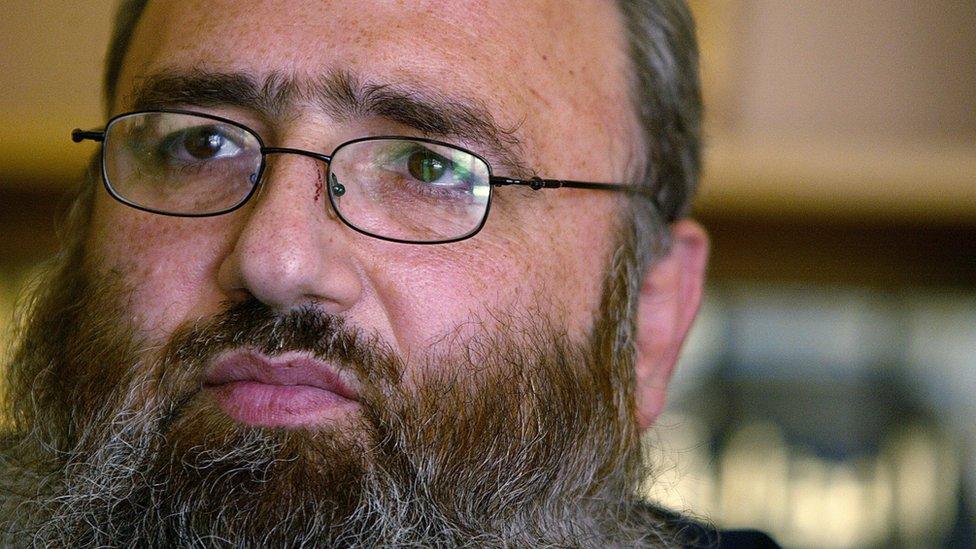

The radical preacher Anjem Choudary has been released from jail. He's considered one of the most influential and dangerous radicalisers in the UK because of his connection to a long line of terrorism suspects.

His release comes less than halfway through a five-and-a-half-year sentence after being convicted of inviting support for Islamic State. His departure from prison comes approximately four months earlier than it would have otherwise occurred because of the time he spent bailed on an electronic tag before his conviction. But it does not mean he is free to do as he pleases. So how dangerous is he - and what is being done to manage the threat security chiefs believe he poses?

Who is Anjem Choudary - and what did he do?

Choudary headed the Al-Muhajiroun (ALM) network. This was the leading group in the UK that supported an extreme interpretation of Islam that advocated Sharia law for Muslim lands and, ultimately, an inevitable conflict with Western liberal democracy.

The network, which had various guises, franchises and what amounted to brand names, was progressively banned under terrorism legislation in the wake of the 2005 London attacks.

When its founder, a Syrian Islamist cleric called Omar Bakri Mohammed, fled the UK following those attacks, Choudary, as his key disciple, took the helm.

British-born Choudary is charismatic and media-savvy and, in his drive for members, he would regularly make headlines with events such as high-profile demonstrations.

Choudary was a follower of another radical Islamist figure, Omar Bakri Mohammed

These would regularly involve denouncing the West and Middle Eastern regimes, the war in Iraq, Afghanistan and anywhere else where he could claim that Muslims were victims.

Did Anjem Choudary organise terrorism attacks?

No. His danger came from the role he played in radicalising others. Once his followers bought into the idea that the West was victimising Muslims, that opened the way to them choosing violence themselves.

In many ways he was no different to many violent revolutionary ideologues through history: creating the conditions of hostility, without ever picking up a weapon himself.

Terrorism researcher Hannah Stuart, who has studied British jihadists since 1999, discovered that ALM was a factor in the lives of at least a quarter of those who have carried out attacks, gone to fight overseas or ended up in jail.

These included:

Omar Sharif - a British suicide bomber who attacked Tel Aviv in 2003. He was a follower of the ALM network.

Ten years later Michael Adebolajo murdered Fusilier Lee Rigby in London. Choudary confirmed the killer had been a follower - but said he had left the group.

"Boy S" from Blackburn was the youngest ever teenager to be convicted of a terrorism offence in the UK after he tried to organise an attack via his smartphone in his bedroom. He was under the spell of one of Choudary's circle - and met the leader himself before developing his plans.

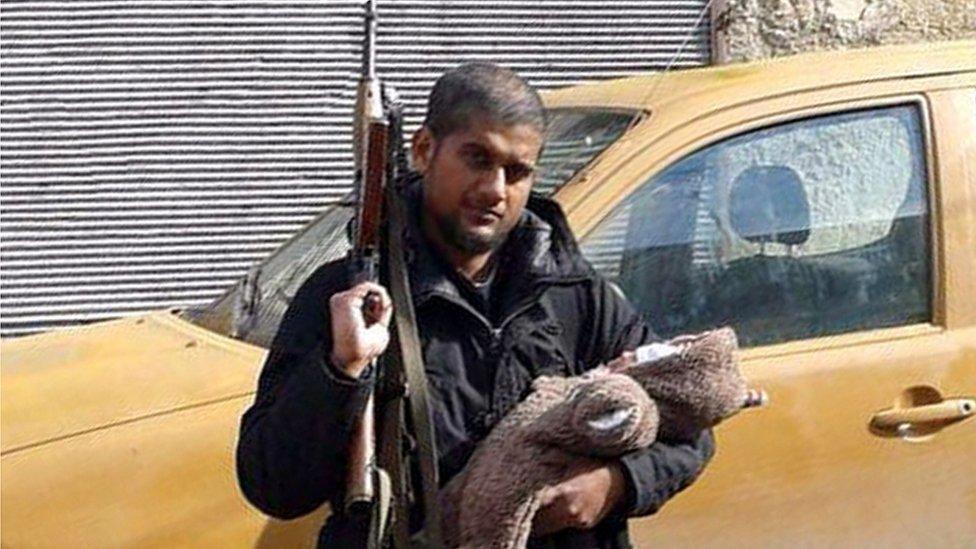

Siddartha Dhar - one of Choudary's closest lieutenants in London - skipped police bail while under investigation and turned up in Syria fighting for the Islamic State group.

How big was the network?

It's very difficult to measure - and if MI5 ever worked it out, they're unlikely to put the figure in the public domain because it would give away exactly what they knew. But al-Muhajiroun and Anjem Choudary were influential in two ways.

First, there was personal contact. The core of the ALM network was quite tight and focused on a few centres of organisation, including London's East End and Luton. Sometimes he could attract more than 100 supporters to a demonstration - other times half a dozen to man a prayer stall in a town centre.

But he also had supporters online. Choudary and his core preachers were prolific on YouTube. They hosted video conferences on private platforms and spread messages far and wide via social media messaging services.

Some extremists were part of the network but not necessarily part of the inner circle, such as Khurram Butt, one of the three men who carried out the London Bridge/Borough Market attack in 2017.

Why is Anjem Choudary being released now?

He has reached the halfway point of his five-and-a-half-year sentence.

He spent some of this sentence in a special "separation unit" for dangerous extremists inside Frankland Prison in County Durham, to limit his possible influence over other inmates.

Now he is leaving jail, he is not going to be free. When an offender is released at the midway point of their sentence, the remainder is spent on "licence" in the community, as part of attempts to reintegrate them and reduce the risk of reoffending.

He must comply with 25 conditions that his release team, made up of probation and police officers, believe are necessary and proportionate to manage the risk he may still pose.

If he breaches them, he risks being recalled to prison.

Anjem Choudary spent some of this sentence in a "separation unit" inside Frankland Prison in County Durham

These conditions have been headlined as being among the strictest ever - but the truth is a little more prosaic. They're taken from a wide menu of options that are used to manage the risk of people convicted of a terrorism offence.

In Choudary's case, the risk is that he will not have changed and could radicalise others once more.

While in prison he refused to take part in deradicalisation courses or exercises, the BBC has learned from counter-extremism sources.

On a number of occasions, Choudary was offered opportunities to speak to mainstream religious leaders and other experts who have successfully turned around the mindset of other extremists. On each of those occasions, Choudary refused to get involved.

While the preacher reportedly refused to address his mindset, prison authorities could not hold up his release.

The restrictions he will face for the next two-and-a-half years therefore include a ban on preaching, organising meetings, associating with members of the ALM network, using the internet without permission or giving media interviews to spread his message.

He's also under a UK travel ban - restricted to within Greater London's M25 - as well as barred from foreign travel without permission. In other words, he will be carefully monitored.

What about his associates?

When Anjem Choudary was charged in 2015 with inviting support for IS, it was a moment of great success for counter-terrorism chiefs - and they were already trying to build cases against other associates.

Michael Adebolajo (left) was a follower of Anjem Choudary (right) before killing Fusilier Lee Rigby

Some, including close confidantes, were jailed. At least four others, who cannot be named for legal reasons, were subject to a Terrorism Prevention and Investigation Measure (TPim), a form of control that places two years of restrictions on the movements and activities of terrorism suspects who have not been charged with a crime.

Others were investigated by social services as to whether they posed a risk to their own children or others. There was also an attempt to use Anti-Social Behaviour Orders against targets from Luton.

Detectives also looked for evidence of standard crimes - such as fraud - as a means to further "disrupt" the network. At least one member of the wider ALM family was jailed for fraud.

The insider view is that this work has been generally successful because it made the targets aware they could no longer act with impunity.

In theory, it created space for the security service MI5 and their police detective colleagues to focus on more urgent threats.