Could teen jihadist have been saved from himself?

- Published

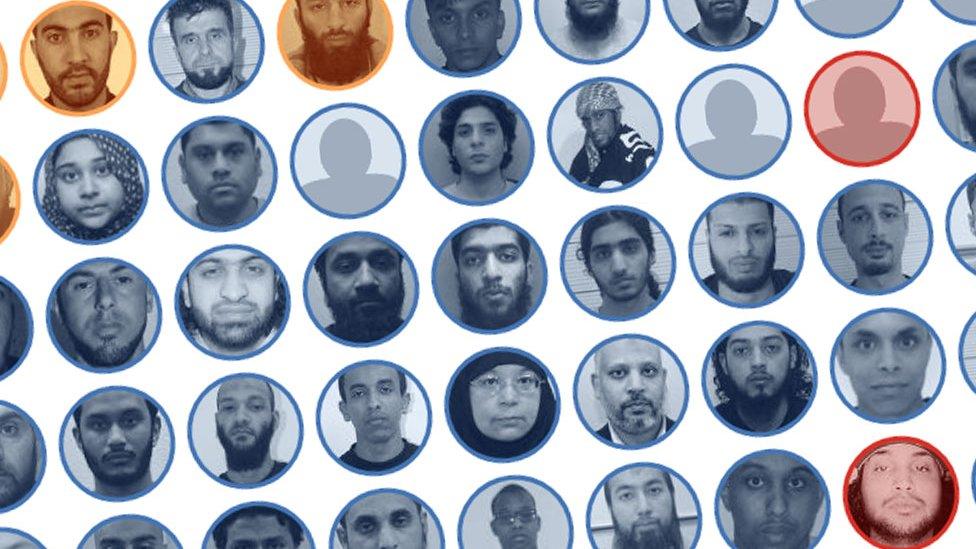

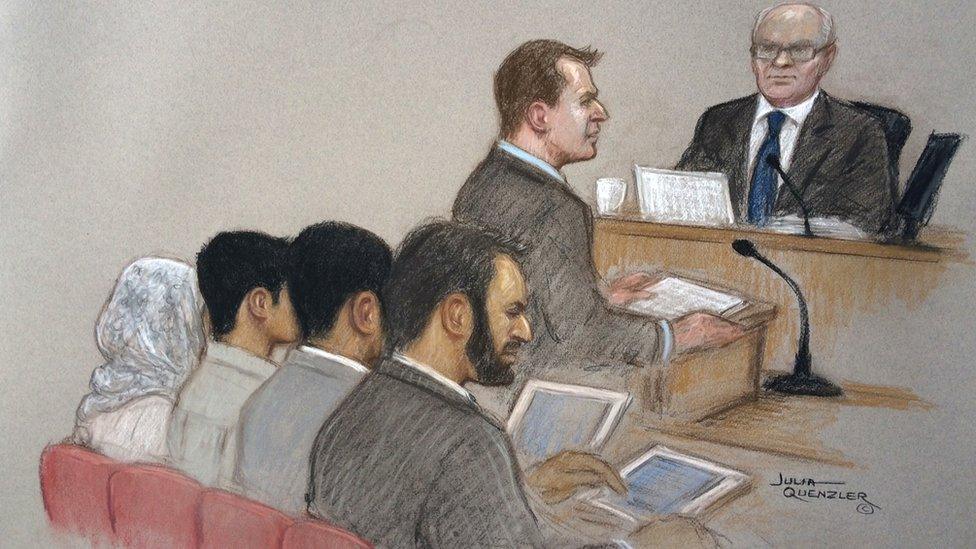

Boy S was sentenced to life in prison at Manchester Crown Court. He and his family are obscured in this picture

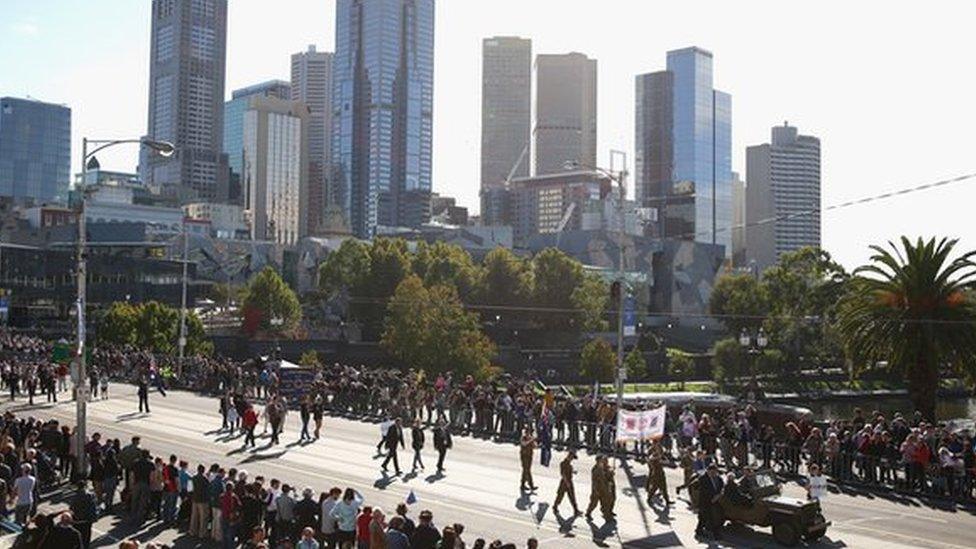

A boy who attempted to incite a man in Australia to carry out an Anzac Day "massacre" has become the the youngest person in the UK to be convicted of a terrorism offence.

The teenager - who was referred to as Boy S in court and was 14 years old at the time - was given a life sentence and told he must serve a minimum of five years behind bars.

But could more have been done to challenge and stop the development of his violent mindset?

The boy's slide into extremism began more than two years ago, at a crucial period in his development.

His parents had separated, he changed schools, and he was developing a deep interest in world affairs. This was fed through his newly acquired smartphone.

From February 2013, he was failing to settle into his new school. He was abusive, disobedient and quickly excluded.

At home, his mother didn't want him associating with local youths, so he was spending hours online in his bedroom, apparently studying foreign affairs.

The boy grew up in Blackburn, Lancashire

On 23 October 2013 - now back in school - he praised Osama Bin Laden and declared he wanted to die a martyred fighter's death.

Teachers talked to local officials involved in preventing extremism and he was referred to the national deradicalisation scheme, Channel.

The scheme operates at the very sharp end.

If police and other agencies identify a potential extremist - be they inspired by al-Qaeda, or neo-Nazi ideology - a meeting is arranged with a specialist who can help the person confront where they are heading.

Its single aim is to get the potential extremist to change before it is too late.

Boy S was referred in November 2013 - but it was another three months before he entered the process. Blackburn and Darwen Council, the lead body in the case of this teenager, wouldn't tell the BBC why there was such a delay.

However, once he was seen and assessed, local officials recommended moving him to a secure school for troubled children.

Once there, he became even more unhappy, alienated and aggressive.

He told one teacher he would stab him in the neck with a pencil and subject him to a "halal" slaughter. It was just one of many threats to kill.

"I felt angry, very angry with all of them," the boy has since said of his school, according to defence submissions.

"I just wanted to get excluded. You couldn't run away, it was secure with locked doors. The best way to get out and go home was to threaten staff with beheadings.

"I found the more I did this the more free time I had and I could get home on my phone."

In July 2014, Channel closed his case because officials thought he could be best supported through social services.

That decision came despite earlier proposals to set him up with a professional mentor.

By the autumn of 2014, Boy S was talking openly about beheadings. He showed teachers an appallingly violent video on his mobile phone.

And when he told teachers he had a beheading list, including the order in which he would kill them, he was referred to Channel again.

Before the second intervention began in January 2015, the boy went on a family trip to London. While there he met an extremist preacher, whom we cannot name for legal reasons.

Boy S followed the preacher's advice to get on Twitter. That proved to be a gateway to a series of extremist contacts, including leading figures inside the self-styled Islamic State group.

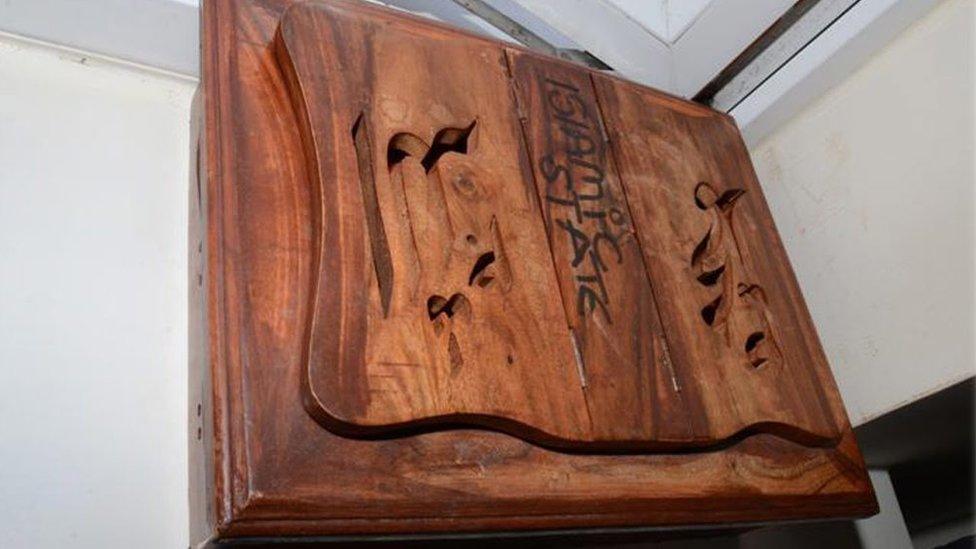

Police found a wooden box labelled "Islamic State" in the boy's bedroom

Later that month, he met for the first time a "deradicalisation intervention provider" - a mentor capable of challenging his mindset.

That mentor, known only as Witness A, concluded that of the dozen cases he had taken on, this boy was the most radicalised he had seen.

And he warned that someone was taking advantage of the teenager.

One of those people, Manchester Crown Court was told, was Abu Haleema, a self-styled London preacher who featured in an extremist social network that led to and maintained the boy's radicalisation.

During a session with the mentor, Abu Haleema sent Boy S a link to a page about a woman being beheaded.

In a phone conversation with BBC News, he confirmed that he had spoken to the teenager - and he claimed that at one point the boy had asked him whether he should kill an imam with whom he disagreed.

Abu Haleema insisted he told him that it would be wrong.

He has been interviewed by the police and has not been charged in relation to this case.

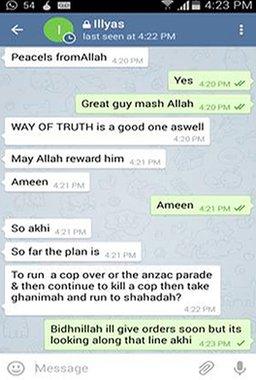

The boy sent thousands of messages to a man in Australia, Sevdet Besim, since charged with preparation of a terrorism attack

In a final meeting with his mentor, Boy S said he wanted nothing more to do with him unless he stopped working with the Prevent team - the government's counter-terrorism strategy.

"I only have my phone and you even want to take that off me," he said.

In March 2015, Channel officials threw in the towel and passed the case to the North West Counter-Terrorism Unit. Boy S was arrested on suspicion of making threats to kill.

When police undertook a full examination of the boy's mobile phone they found it was filled with extremist material.

Not only was there evidence of the Australia plot, but Boy S had also tried to incite a French man to carry out an attack, radicalised an American woman to raise her children as suicide bombers, and talked to a South African girl about going to Syria.

He was operating 89 Twitter accounts - and among those were evidence that he was in direct contact with leading IS figures.

Police discovered Boy S had formed an online relationship with a girl from Manchester who held similar pro-IS views.

In August, she pleaded guilty to possessing a recipe for explosives.

Unique circumstances?

Did Channel make mistakes? Could it have done more or were its officials simply confronted with someone they could not turn around? Well, we don't really know.

Harry Catherall, chief executive of Blackburn with Darwen Council and chair of the Lancashire Contest Board - the official body that overseas counter-extremism work in the county - has issued a statement commending the local partnership for preventing an atrocity in Australia.

But the council would not tell us whether it had reviewed how the boy's case was handled - or whether, with hindsight, it would do anything different.

"No doubt lessons can and have been learnt by many people from the unique circumstances of S's case," said the judge, Mr Justice Saunders.

"But there is no material before me from which blame should be attributed to anyone, except those extremists who were prepared to use the internet to encourage extreme views in a boy of 14 and then use him to carry out terrorist acts."

So what happens now to Boy S? Can his extremist identity be deleted?

More specialists will be brought in. The defence team argued that Boy S can be changed.

But if he doesn't, the life sentence imposed on Friday means he could stay in prison forever.

- Published2 October 2015

- Published2 October 2015

- Published1 October 2015

- Published12 October 2017