End of life care: How to talk about dying to someone who is dying

- Published

Becky Bevers' first question to doctors was: "Am I going to die?"

When Becky Bevers tells people about her incurable breast cancer, she is met with all sorts of reactions. Some people are awkward, even crossing the street to avoid talking to her, while others are just stuck for words.

So what should you say to someone with a terminal illness?

"I'm very open about everything and not afraid to talk about it - but other people are," says Mrs Bevers, 51, who lives in Minehead, Somerset.

She was diagnosed with advanced, stage four breast cancer last year, describing the moment as "like being smashed with a sledgehammer".

It is under control - "I'm not imminently going to pop my clogs" - but doctors do not know how long it can be treated for.

"In the early days there was total avoidance by some people who couldn't cope," she says.

"Or because I don't look unwell, I have met acquaintances who said 'you don't look ill' - like I'm a charlatan or I'm lying, almost accusatory."

But the approach she has welcomed from friends and family is to ask any questions and ask how they can help.

"Just listening, putting in a phone call, dropping a text, making yourself available," Mrs Bevers said.

And the worst things for her? "Don't shy away from it. Don't try and give me advice. Don't go all sympathetic and say you poor thing. I feel desperate enough as it is without others' desperation.

"The worst thing is when people say 'try to stay positive'. I am such a positive person but I have had my moments, I have been on the floor sobbing."

'People are generally uncomfortable'

Hannah Bonnington, 36, was diagnosed with triple negative breast cancer, a rare form of the disease, in April last year, just before her son's first birthday. In August this year she was told the cancer had spread.

"The stats say it's unlikely I'll see 38," she says.

She said, based on her experience, doctors can "focus on the positives and the treatments and sometimes the reality gets a bit brushed under the carpet".

Hannah Bonnington, a surveyor, says she wants "a bit more realism and frank conversations to normalise dying"

"I have no idea what my end of life will look like, whether it will be painful, whether it will be drawn out, whether I need to look at hospice care," she said.

"They [doctors and nurses] feel reluctant to have these conversations because they are so focused on saving your life."

It comes as a report published on Friday from medical experts has said doctors need to get better at having these difficult conversations with dying patients.

Mrs Bonnington, from Highbury, north London, says she talks about dying openly in order to come to terms with it so she can "move on with the rest of my life".

"I'm quite blunt and make jokes about it, like saying 'I've only got a year to live, I'm not spending time doing that'."

But she thinks people "are generally uncomfortable" talking about death. For her, one problem can be when people "close down the conversation or sometimes try and change the subject".

Her advice for anyone with a friend or relative with a terminal illness is to "take your lead from the person it's happening to".

"Some people want to bury their head in the sand and it's their life, they can do that."

'Cowardice'

When Peter Buckle's wife, Wendy, was diagnosed with a brain tumour in 2010, he says the neuro-oncologist "never once told us that it could be terminal".

"It must have been about four weeks before she died I happened to speak to the neuro-surgeon.

"He said 'I suggest you get some hospice care lined up'. That's the first indication that it was terminal."

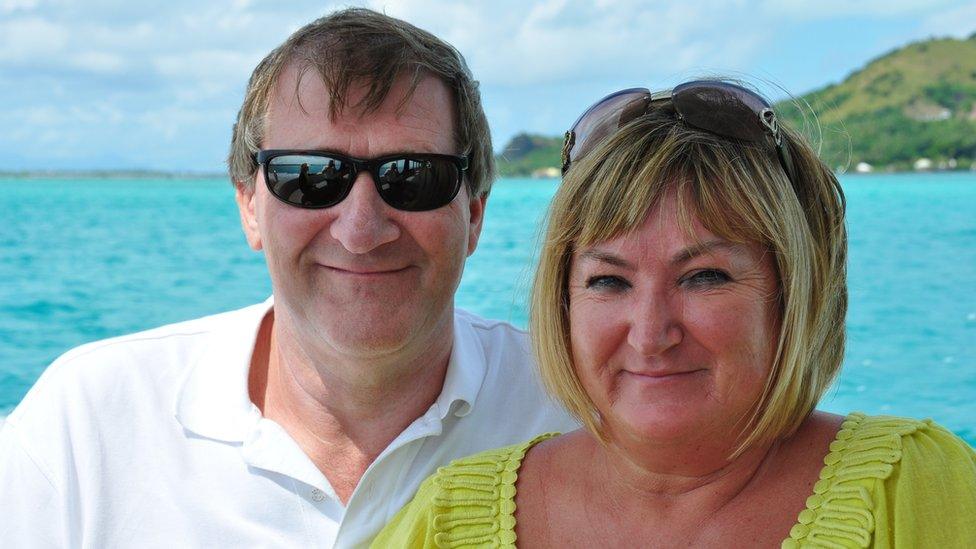

Peter Buckle and his wife Wendy, who died in 2011, on one of their last holidays

He said that when it became "absolutely clear" that Wendy was going to die, the "crash" was so much larger than it might have been had they had been told earlier.

Mr Buckle, 64, who now volunteers for the Marie Curie charity, said: "I have heard so many people say 'of course you have got to give the patient a sense of hope'.

"I think it's just cowardice, it's just avoiding what needs to be done.

"I think if we'd had that prognosis, we'd have lived those last months differently."

'Will I die today?'

Louise Hatchard, who is an advanced nurse practitioner at Fair Havens hospice in Essex, spends time with dying patients every day - and says there are two groups.

"Some don't want to know full stop," she says. "Some people prefer to live in complete ignorance. We have to respect that. Then other patients do want to know."

Hospice nurse Louise Hatchard says staff do not give timescales, but might say "short days" or "short weeks"

"The very difficult thing about it is the uncertainty," she adds.

"I have literally just come out from talking to a lady who asked me the question: 'Am I going to die today?' The honest answer to that is I don't know.

"You then talk about how poorly she is and what she thinks and explore her feelings. Our cues always come from the patient."

She stresses that staff "do not give false hope" and answer the question "as honest and openly as we can".

"Really you have one chance to get this right for them. You need to give them the chance to say things or do things they need to do.

"Maybe their last wish is to see the sun setting, if you don't have these open conversations then you never know."

Macmillan can help to provide practical and emotional support on matters relating to end of life and bereavement. To access their services visit the website, external or call the support line free of charge (0808 808 0000).

Marie Curie also provides help about talking about death., external

- Published19 October 2018

- Published14 May 2017

- Published2 March 2018

- Published6 October 2015

- Published14 September 2018