The UK towns and cities worse off than 100 years ago

- Published

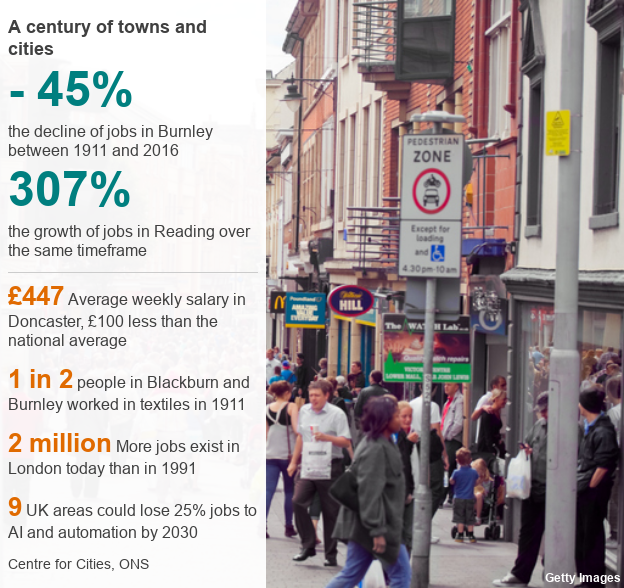

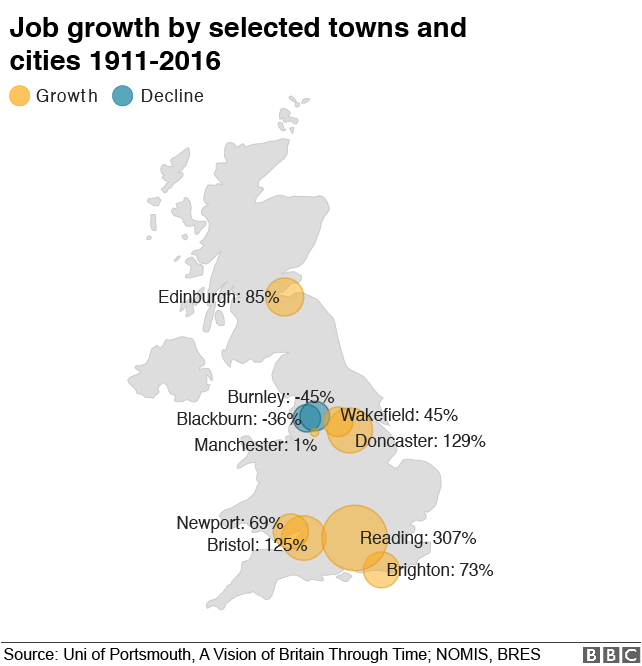

Over the past 100 years new industries and new ways of working have divided the UK's towns and cities into haves and have-nots.

Some have managed to make the transition, while others have been unable to recreate the boom they enjoyed in the early 20th Century.

Why have some cities managed to stride ahead, while others have fallen by the wayside?

Funding, infrastructure and opportunity all play a part, marking the difference between the places able to adapt and those forced into a cycle of low-paid, low-skilled jobs.

The reinventors

In the decades after World War Two, London's economy fell into long-term decline. The disused industrial cranes that lined the Thames told the story of a city struggling to come to terms with a rapidly changing world.

Between 1951 and 1991, London lost 800,000 more jobs than it created, mainly because of the collapse of its manufacturing sector. Its population fell by about a million.

But the capital has since seen a huge turnaround in its fortunes thanks to an explosion in "knowledge industries" like finance, media, marketing and technology.

These offer higher-skilled, higher-paid jobs, whose main products are information and ideas rather than physical goods.

The result is there are about two million more jobs in London today than in 1991, with world-leading businesses in many different fields.

London's story underlines the challenge that most UK cities have faced - how to cushion the decline of heavy industry by creating jobs in emerging industries.

A number of other cities have successfully reinvented themselves as centres of knowledge production.

A century ago, Edinburgh, Bristol and Leeds were home to low-cost, traditional manufacturing. Today they are hubs for finance and creative occupations, with Leeds recently announced as the new home for Channel 4 television.

They built on an existing history of jobs in activities such as accountancy, bookkeeping and goods trading - the "knowledge jobs" of the early 20th Century.

Manchester has also made this transition, creating knowledge-based jobs in financial services, law and advertising - driving the resurgence of its vibrant city centre.

But because of the heavy job losses it suffered through the middle part of the century, it only has 1% more jobs than it did 100 years ago.

Many other towns and cities have struggled to adapt after facing big job losses in their traditional industries. When compared with more successful places, they are arguably worse off in relative terms than they were 100 years ago.

Instead of reinventing their economies, they have had to "replicate" them - swapping coal mines for call centres and dockyards for distribution sheds, for example.

These cities tend to have created more jobs than they have lost in recent decades, but they have generally been in lower-skilled work.

Doncaster is one such example. Little remains of its mining industry, which at its peak in 1931 employed 36,000 people, 50% of the town's workers.

Today, the town actually has more than double the number of jobs than it did a century ago.

But the challenge is that these jobs are dominated by sectors like warehousing and distribution, which tend to be lower skilled than those in knowledge industries.

They are lower paid and less secure - with shop, administration and warehouse jobs likely to be among those most at risk of being replaced by robots and artificial intelligence.

As a result, Doncaster has the fifth lowest average wages among the UK's largest towns and cities. At £447, they are £100 lower than the national average, although the cost of living is also relatively low.

The same story has played out across many other towns and cities with a legacy in heavy industry, such as Birkenhead, with its strong tradition of shipbuilding, Middlesbrough, the home of steel and chemicals, and Wakefield, which like Doncaster, has a proud mining heritage.

Increased competition from abroad and the mechanisation of many jobs continues to squeeze their key industries. Many of the services they once offered are either no longer needed, or can be done more cheaply and efficiently elsewhere.

Filling the gap

Other places have struggled to recreate even low-paid jobs.

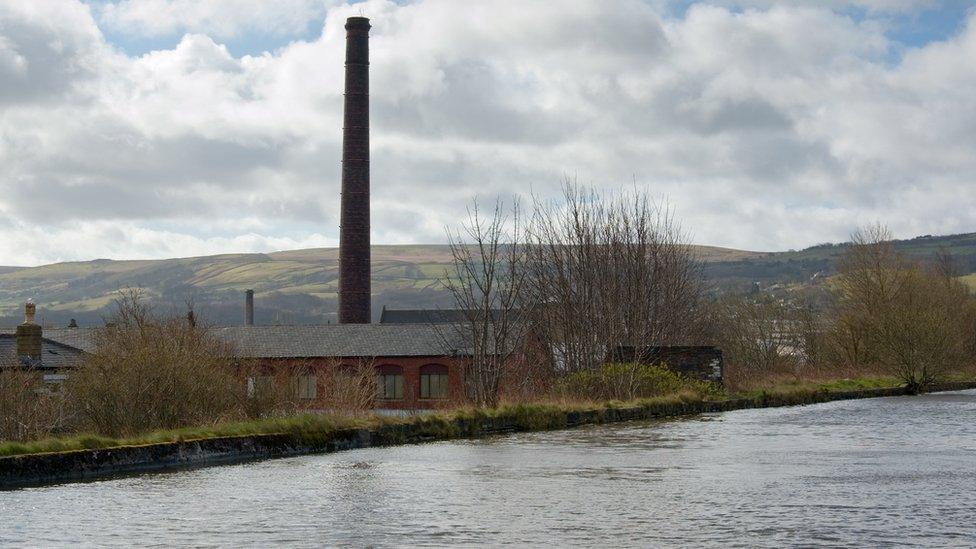

The chimneys that punctuate the skylines of Burnley and Blackburn offer a reminder that in 1911 one in every two people worked in the textile industry.

Both have witnessed decades of decline. They now offer about 50,000 and 40,000 fewer jobs respectively than 100 years ago, while their populations have also shrunk.

These areas have been unable to adapt in the face of a century of change, although they have been helped by a relatively high proportion of public sector jobs.

Educational divide

How can struggling towns and cities take a greater share of highly paid jobs?

Residents' ability to access higher education is a big part of the puzzle and research suggests a regional divide in this respect.

London children receiving free school meals are 40% more likely to achieve good maths and English GSCEs than these children in the north of England. A child receiving free school meals in Hackney is three times more likely to go to university than their counterpart in Hartlepool, for example.

More than half of London residents have a degree, compared with one in three living in north-west England., external

Not only are graduates likely to earn more throughout their lifetime, they also provide a boost to their local area.

Knowledge-based businesses tend to invest in places where they can get the skilled workers they need. They often want to base themselves in the same place as similar businesses, where they can pool resources, network and keep an eye on their competition.

What follows is a vicious cycle, where cities that don't offer access to these benefits can't attract high-level jobs, or people with the appropriate skills to do them.

Others have argued that struggling towns and cities have not always had the tools they need to respond to change.

Historically, the centralised nature of UK government means many have had little control over policies like planning, investment and transport. This has started to change under devolution and with the creation of seven metropolitan mayors - including those in the Tees Valley and the West Midlands.

The last 100 years has created winners and losers across the country. The winners have been those cities able to adapt to an ever-changing economy.

In future, all cities will need the tools to attract tomorrow's industries and adapt to whatever change lies ahead.

About this piece

This analysis piece was commissioned by the BBC from an expert working for an outside organisation.

Andrew Carter is chief executive and Paul Swinney is head of research and policy at the Centre for Cities, which describes itself as working to understand how and why economic growth and change takes place, external in the UK's cities.

Edited by Eleanor Lawrie

- Published22 June 2018