Knife crime: Should stronger stop and search powers be used?

- Published

A series of stabbings on the streets of London has led to a renewed focus on knife crime and how to reduce it.

One power available to the police is stop and search, and Home Secretary Sajid Javid has recently emphasised its importance in tackling violence:

"If stop and search means that lives can be saved from the communities most affected, then of course it's a very good thing," he told the annual Police Superintendents' Conference, external in September.

But what powers are available to the police and what is the evidence they reduce crime?

The powers

There are three main acts that allow police forces in England and Wales to carry out stop and searches.

Section One of the Police and Criminal Evidence Act 1984

Section 60 of the Criminal Justice and Public Order Act 1994

Sections 44/47A of the Terrorism Act 2000

Last year, 99.1% of all searches were carried out under Section One and what the Home Office calls "associated legislation", including the Misuse of Drugs Act 1971. These powers allow the police to conduct a search if they have "'reasonable grounds" to suspect someone of carrying illegal drugs, a weapon, stolen property or something which could be used to commit a crime, such as a crowbar.

Section 60, on the other hand, allows officers to search anyone in a designated area without "reasonable grounds". It applies when the police have intelligence that serious violence has taken place or may take place.

Section 44/47A allows the police to conduct searches when there is "reasonable suspicion" an act of terrorism will happen. Before last year it had not been used since 2011, but 149 searches were carried out using the power following the Parsons Green bombing in September 2017.

Unfair targeting

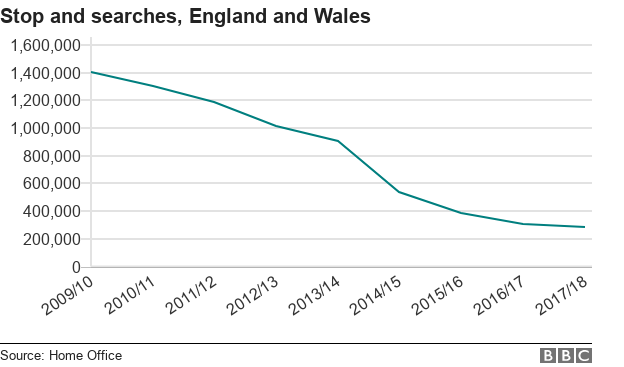

The police used a combination of all these powers to search 282,000 people across England and Wales last year.

That represents an 80% drop from the 1.4m searches in the year ending March 2010.

Stop and search occurrences began falling in 2009, following fears that it was being used too widely and was unfairly targeting ethnic minorities, especially young black men.

The government brought in measures to limit its use in 2014 and this led to the creation of a revised code around its use., external

Section 60 searches quadruple

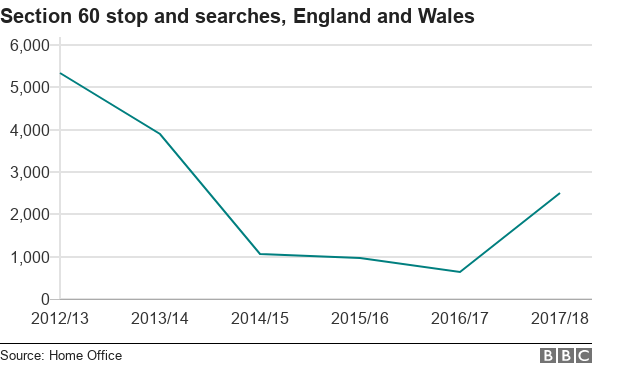

While stop and search has fallen overall, the Home Office's data reveals that searches carried out under Section 60 rose last year., external

In the year ending March 2018, they quadrupled compared with the previous year - 2,501 were carried out in 2017/18 compared to 631 in 2016/17, external.

This was the first rise in Section 60 searches for nine years.

When used, Home Office guidance recommends that a Section 60 should initially last no longer than 15 hours, external.

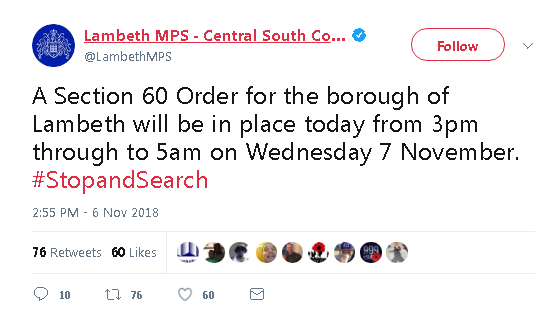

The police should publicise - usually through social media - where and for how long a Section 60 order is in place.

For example, the Metropolitan Police imposed a 15-hour Section 60 order, external across the whole of this year's Notting Hill Carnival in August. It said the decision was based on "detailed analysis of intelligence".

Police forces will often use social media to alert the public when a section 60 order is in place

Why has Section 60 use increased?

Most of the increase in Section 60 stop and and search incidents has been driven by the Metropolitan Police, which carried out 73% of all Section 60 searches last year.

In an interview with the Evening Standard, external in April, the Metropolitan Police Commissioner, Cressida Dick, said she would give the go-ahead for her officers to use the Section 60 power to crack down on gang violence.

The majority of Section 60 searches are carried out by the Metropolitan Police

The Met's Assistant Commissioner Martin Hewitt says the use of Section 60 is an important way of preventing violence.

"It's a legitimate and powerful tool," he told BBC Reality Check.

"Disputes between young people can quickly turn into violence and Section 60 is a preventative measure based on police intelligence," he argues.

Does stop and search work?

The government's Serious Violence Strategy, external, published in April, acknowledges that knife crime, gun crime and homicide have all risen as stop and search has fallen. But it dismisses any link, pointing out that knife crime fell between 2010-11 and 2013-14 - a period that also coincided with a fall in stop and search.

Last year the College of Policing published a study, external examining Metropolitan Police stop and search data. It found that higher rates of stop and search, under any power, only led to "very slightly lower than expected rates of crime in the following week or month".

Another way of trying to assess the effectiveness of stop and search is to look at arrest rates.

And on that measure, the data shows that as fewer people are searched, the more likely those people are to be subsequently arrested.

Last year nearly one in five of the 282,000 people searched under Section One were taken into custody - that compares with almost one in 10 in 2009-10.

This suggests that as Section One stop and searches fall, it is being better targeted.

The statistics also reveal that 87 people subjected to Section 60 searches last year were found to be in possession of a weapon, a total of 3.5% of all Section 60 searches.

Advocates of stop and search say it needs to increase to act as a deterrent. A report published by the Centre for Social Justice, external - a think tank founded by the former Conservative leader Iain Duncan-Smith - said that some young people were no longer scared of the police, because they believed the risk of being searched was now very low.

On the other hand, if stop and search is used too widely, it can create resentment between the public and the police, argues Leroy Logan,, external a former Metropolitan Police superintendent.

He says this can worsen community intelligence and that the answer to rising knife crime lies in better engagement with young people.

- Published18 July 2019

- Published4 April 2018