National bus strategy: What is happening to passenger numbers and funding?

- Published

The government has unveiled its new strategy for buses in England, involving hundreds of miles of new bus lanes and price caps on tickets.

While the government said its £3bn plan, external would make buses cheaper and easier to use, Labour has said it would not be enough to reverse years of cuts and reduced services.

The Campaign for Better Transport has broadly welcomed the new strategy.

Passenger numbers in England have fallen in the last decade, although buses are still the most frequently used form of public transport.

What has happened to bus travel?

The latest set of official figures on bus use, external in England shows that local passenger journeys fell by 5.5% in the year to the end of March 2020. In the previous year, external, journeys fell by 0.7%.

Covid had some effect on the 2019-20 figures, with bus companies saying they had seen a decline in passenger numbers in the weeks before the first lockdown began on 23 March.

Since then, the pandemic has had a considerable impact on bus usage, with journeys falling, external 38% between July and September 2020, compared with the same period of 2019.

About half of passenger journeys in England occur in London. But its figures are generally seen as separate to the rest of the country, because its buses operate on a different system.

Transport for London plans routes and dictates service levels, whereas in the rest of the country bus operators have considerably more control over how they operate.

Outside London, buses are largely run by private companies, which make their money from passenger fares. Then, local councils pay subsidies to plug the gaps, often in rural areas where running a route is more expensive or less lucrative for companies.

Areas where running a bus service is the least lucrative for private operators, will rely most on council subsidy.

What has happened to council spending on buses?

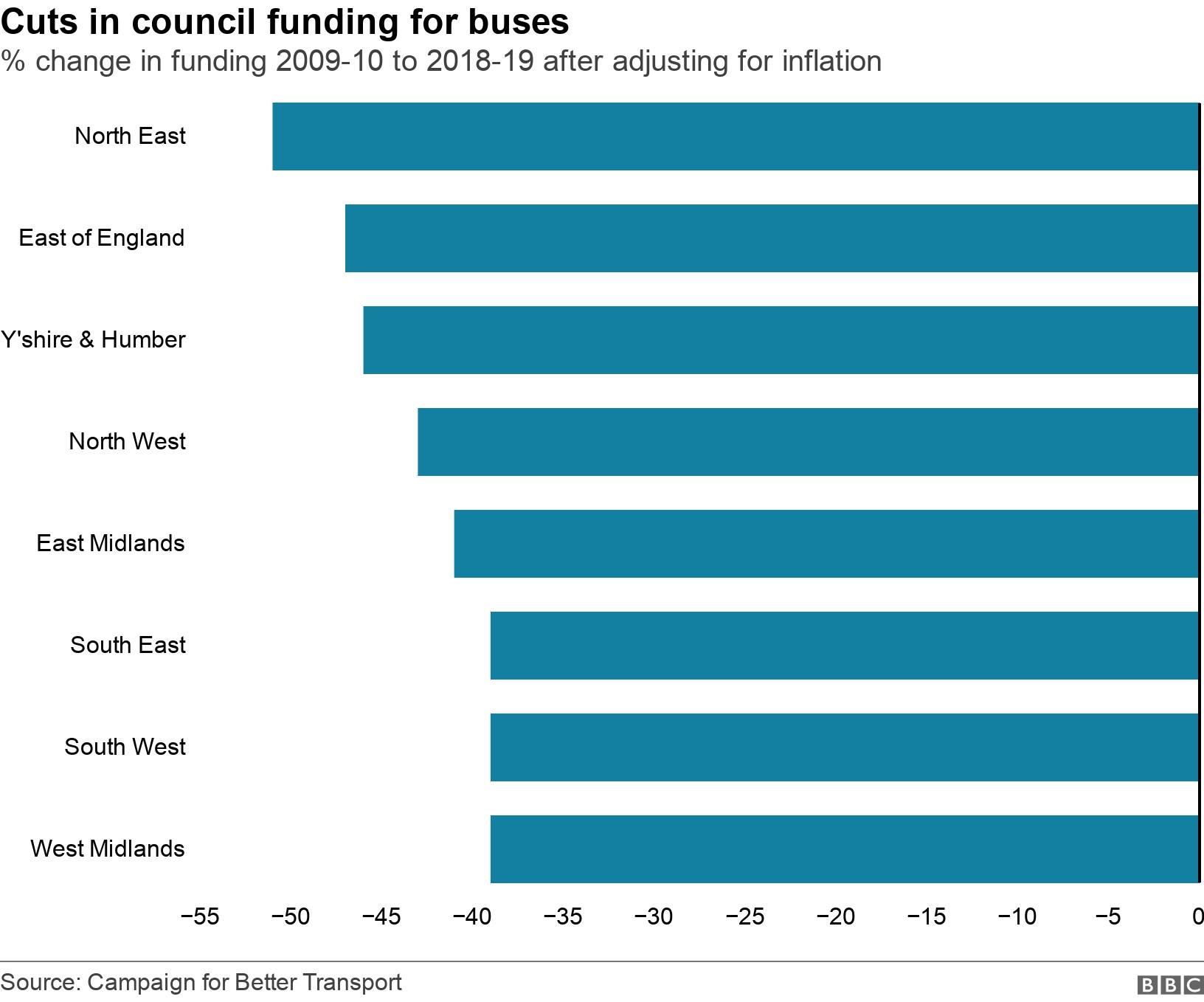

According to figures from the Campaign for Better Transport, the amount spent on bus services by councils in England has fallen.

The figures, based on Freedom of Information requests, show that spending on supporting buses in England (excluding London) was £219m in 2018-19, which was down 43% compared with a decade earlier, after adjusting for inflation.

That is against a backdrop of central government austerity measures, which has seen local government spending on services falling by, external an average of 21% over the same period amid strict restrictions on council tax increases.

The campaign group releases these figures annually, but did not produce a report in 2020 due to the pandemic.

Don't councils have a duty to support bus travel?

If bus cuts and fare rises leave some people unable to get around, don't councils have a duty to do something about it? In fact, councils have very few specific obligations around buses, making them an easy target for councils as the cuts bite.

There are specific things they legally have to do, for example provide transport for children who are otherwise unable to get to school.

They also have to make sure there are concessionary fares for older and disabled people. Although this is partly funded by central government, the grant has been falling, leaving councils to make up the difference.

But other than that, they are not obliged to fund buses or to ensure everyone has access to them.

It's possible a council could be challenged in the courts under equality legislation, if it could be shown to be disproportionately restricting certain groups of people.

But legal guidance suggests it would be difficult to challenge a council, if it could show it had assessed the needs of a local area and the impact of removing a bus service, particularly on elderly and disabled people.

If, after this assessment, councils decide they need to make cuts because of a lack of funds, this would be likely to be legal. But councils can't let bus cuts leave a community that needs transport, with no transport service at all.

And in some areas, councils have used community transport services - often minibuses driven by volunteers - to fill the gaps.