Why vox pops are important

- Published

"A parade of ignorance and prejudice." "Cheap filler." "Lazy journalism." "Can't you find any proper news?"

The vox pop, the news segment where reporters ask the opinions of the public, comes in for some pretty hefty criticism on social media and elsewhere. But far from dismissing it as pointless padding, I believe it is a vital ingredient in trying to understand Britain - and never more than now.

I am not going to defend the bad vox pop. You know the kind of thing: people are asked a simplistic question in a shopping precinct and we broadcast one person saying yes, one person saying no and the "hilarious" response of someone who misunderstands the question.

That is not only pointless, it is also patronising and disrespectful. Broadcasters reduce the voice of the people (the meaning of "vox populi") to the equivalent of TV wallpaper paste and, more importantly, we learn nothing.

But there is so much to learn from listening to people, giving them the chance to offer a view, however incisive or ill informed we might think those opinions are. Vox pops are not scientific tests of public opinion but they often tell us something important about what is bubbling away below the surface.

Shopping streets are regularly used for vox pops

I often say that my role at the BBC as home editor is to tell the story of changing Britain. I do quite a lot of "vox-popping", in different forms, because if we want to understand our country, I believe we must take the time to find out what the populace feels and thinks.

Some may argue that Brexit is, in large part, a consequence of our leaders failing to hear the voice of the people; the widespread sense that the "elite" are not listening, out of touch and aloof. "Taking back control" was a battle-cry that resonated with many who felt power had shifted to ivory towers.

For decades, mainstream politics avoided the subject of immigration, for example. Only by listening to the conversation at the bus stop or the chat in the cafe would you have learned of the disquiet communities felt at rapid demographic change and the consequences of globalisation, anxieties that often only emerged over a second cup of tea.

A vox pop, well conducted, can be a highly effective way to test public opinion and mood.

Traditional polling is quite a blunt tool. It is good at telling you, broadly, what people say in answer to certain questions - and there is a science to the results. But it is less good at understanding why people answer the way they do. You need to probe beyond question one and, quite probably, beyond question two and three too.

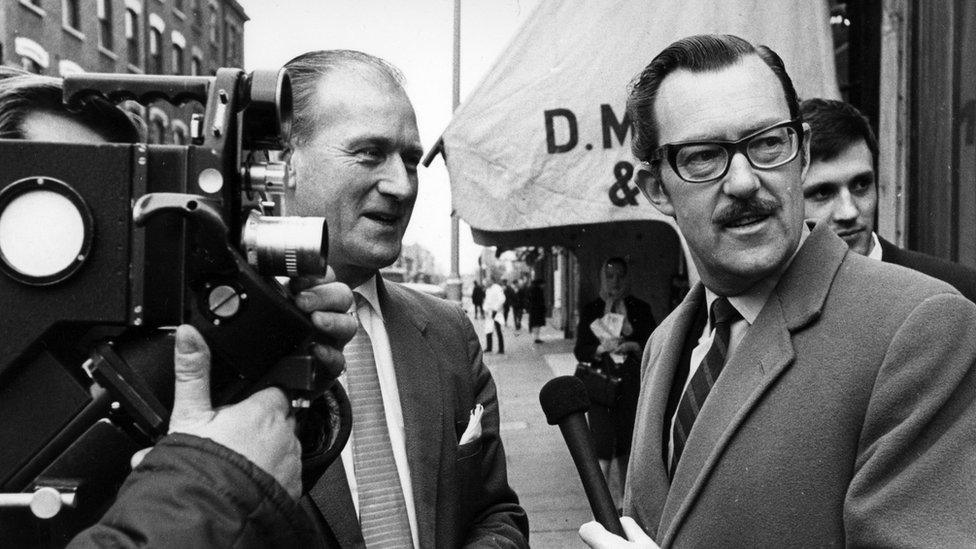

The television reporter Alan Whicker helped popularise the vox pop in the UK

When you give people the time and the space to explain themselves, you start to reveal the gradations, the passions and the confusions that characterise all our views. In a democracy, incoherent or illogical opinions are no less important than the most cogent and consistent. Understanding misunderstanding is essential.

Even stopping people randomly in some High Street and asking them about a pressing topic has value, if you take the trouble to listen, to probe and to listen again.

But even better is to chat to people in a more relaxed setting, in a works canteen or social club or public bar. These conversations can be genuinely revelatory as people consider the trade-offs and complexities of whatever subject we are discussing.

It is surely essential to test the people's response to the decisions of the executive, especially if they are directly affected. Who better to respond to a pensions change than pensioners? Or students to a policy on university loans? Or young mums to reform of child benefit?

Occasionally, we will work with an independent recruitment company to assemble a "jury" of people from a range of backgrounds and political viewpoints. I have conducted a few of these during the Brexit referendum and the recent political turmoil, travelling to Lichfield, Dover, Swansea and, last week, York.

These take their inspiration from focus groups, the intensive discussions that might be used to test the marketing of a soap powder or the branding of a political party. Sometimes, we introduce a "deliberative" element to the discussion, giving people facts and analysis that helps them come to a more informed view.

Mark Easton recently listened to the views of this group of people, in York

What our jury members say is treated with the same respect we would give to the words of a senior politician or leading academic. Almost every opinion will strike a chord with many others.

There is no "wrong answer" in this context. We try to showcase citizens and their views, giving every juror the space to say what they want to say.

This seems only right, especially in the context of a referendum. Whether you have faith in the wisdom of crowds or dismiss the ignorance of the "lumpenproletariat", the process itself gives voice to the people of all backgrounds.

Brexit is really the product of "vox pop" and, if we ever want to understand it and where our country is heading, we must listen to the voices of the people.

So, if I come bounding up to you in your town centre, please understand that I am genuinely interested in what you have to say, and believe that others should be as well.