Gangs: Mistakes that led to grooming scandal 'being repeated'

- Published

Mistakes that led to child sexual grooming scandals are being repeated with gangs, a report by the Children's Commissioner for England has warned.

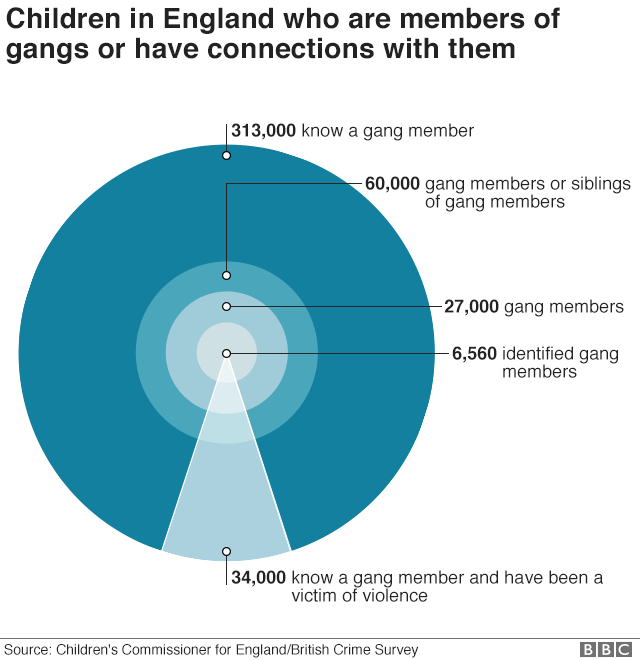

It estimates there are 27,000 children aged between 10 and 17 in England who identify as being part of a gang.

Anne Longfield said gangs were using "sophisticated techniques" to groom vulnerable children and using "chilling levels of violence" to retain them.

The Home Office said it was "committed to protecting vulnerable children".

The report adds that 313,000 children know a gang member - and, of those, 34,000 have experienced violent crime.

Ms Longfield said those suffering from mental health issues or abuse and neglect in their family life were particularly susceptible to grooming from gangs.

A street gang is defined as a group of young people who hang around together and have a specific area or territory, have a name or other identifier, possibly have rules or a leader, and who may commit crimes together.

'The money was rolling in'

Sarah - not her real name - became involved in a gang when she was 12, following a period of physical and sexual abuse at the hands of a family member.

Now 14, she told BBC Radio 5 live that she began by doing drugs such as cocaine with a gang before going on to sell drugs for them - sometimes walking for up to three hours at a time to sell "the tiniest bit of weed".

'Sarah' describes how she was caught up in gangs and dealing drugs - interview voiced by an actor

Her brother, who is two years older than her, was also involved.

"Cos we were so young and we were getting money, we were like, 'Yes, money's rolling in,'" she said.

"We were still both innocent to what was happening because we still both didn't really understand what was going on."

But Sarah was also regularly drinking alcohol and doing drugs, and eventually reached a point where she would "sleep with someone just to get money or just to get a bit of weed".

"It got to that stage where it was really bad and then obviously that's when the police had to step in."

Looking back, Sarah, who is no longer in the gang, says she "hated" who she was - "I was violent, I was just a horrible person."

Researchers said that, for some children, gang membership represents little more than a loose social connection and not all young members are involved in crime or serious violence.

"For many children, involvement in these gangs is not a voluntary act," the report added.

"In some areas children are considered members of a gang based purely on their location, their family or their wider associations."

Grooming 'manual'

Matthew, who was groomed as a child, talks about how he ended up grooming children himself

Gangs have sought to diversify their recruitment as police have become better at spotting "traditional" members, the paper found.

It said techniques for recruiting children are similar to grooming for sexual abuse - as exposed by child abuse scandals in cities including Rotherham, Oxford and Huddersfield - starting with "inducements".

In one case, there was said to have been a "written manual" setting out a clear timeframe for entrapment.

Ms Longfield said gangs then use "chilling levels of violence" to keep them compliant.

"Rather than seeing this as a lifestyle choice that these children are involved in, I want people to see that they are vulnerable children that are being groomed and need protecting," she told BBC Radio 4's Today programme.

The scale of the problem

The report's estimate of the number of children in gangs was calculated using figures from the Office for National Statistics' (ONS) annual crime survey, which asks a representative sample of households about their experience of crime.

For the past three years, it has asked children aged 10 to 15 whether they considered themselves to be a member of a street gang. This figure was then scaled up to give a number for the whole population for a single year.

However the report says that only about 6,500 children involved in gangs are actually known to authorities.

"Many local areas are not facing up to the scale of the problem," Ms Longfield said.

She added that warning signs such as missing school and turning up at A&E with knife wounds were not being acted on and very little help was available for parents who asked for it.

'Treated as a criminal'

By Dominic Casciani, BBC home affairs correspondent

Corey Junior Davis - known as CJ - was shot at close range in a Newham playground in 2017

When 14-year-old Corey Junior Davis - known by his family as CJ - told social services that he needed protection from violent gang members who wanted to coerce him into selling drugs, he was treated as a criminal, not a victim.

CJ was a bright young man - but his severe form of ADHD led to him being excluded from his secondary school. His behaviour worsened - and at the pupil referral unit where he was supposed to be safe, gangs circled as they looked for new recruits they could control.

He was so scared he ordered a bulletproof vest and "Rambo" style knife for "protection".

But when he found the courage to reveal to the authorities how he was being targeted, nobody acted to genuinely protect him.

In September 2017, he was shot and killed in what remains an unsolved murder. An official review found that his local authority completely failed to act on the cries for help from both CJ and his mother, Keisha McLeod.

Today, Ms McLeod says nothing has been learned from her son's awful death. And that's why the Children's Commissioner's warning is so important.

'A national priority'

Responding to the report, the NSPCC said: "Until recently, sexually exploited children were seen as part of the problem and complicit in joining gangs. We cannot afford to make that mistake this time around.

"When authorities come into contact with young people in criminal cases, they must understand how coercion and grooming has lured and trapped these children into committing crime."

Fellow children's charity Barnardo's added: "It's worrying that many children involved in gangs are not known to services.

"Seriously stretched police and social workers are struggling to support growing numbers of children with complex needs, and help is rarely offered before they reach crisis point."

The Children's Commissioner is now calling on the government to make child criminal exploitation a "national priority".

In response, a government statement said: "We have proposed a new statutory duty on partners across education, social services and health to work together to tackle violence as part of a public health approach, and are providing £220m to support children and young people at risk of becoming involved in violence and gangs."

When contacted by the BBC, the children's commissioner for Northern Ireland said it did not have data on how many children were involved in gangs, adding that young people were more likely to be involved in paramilitary groups.

The children's commissioner for Wales also had not collected data on the number of young people in gangs, but said it was taking a "proactive approach" to the issue and held regular nationwide meetings with children's groups.

"Resulting from that we are working with agencies like the police to work in a child centred way, respecting all of their human rights."

The commissioner for Scotland referred the BBC to a study, external that concluded incidents involving gangs of young people using weapons in public places in the country were declining.

- Published15 February 2019

- Published29 January 2019

- Published30 October 2018

- Published16 October 2018

- Published7 September 2017