London population: Why so many people leave the UK's capital

- Published

- comments

It's no secret that London has a very successful economy, not just compared with the rest of the UK but with other international cities too.

Over the past decade its economy has expanded by a fifth. Ever more shops, restaurants and bars have opened to serve its residents.

As a result the population of London and the urban area surrounding it, external has grown significantly, increasing by 1.1 million between 2008 and 2017 to 10 million people.

Yet despite this success story, not everything is going its way.

Many more people pack their bags and leave the capital for elsewhere in England and Wales than make the journey the other way.

Over the past decade, about 550,000 more Britons left London than moved to it.

This trend is not unique to London; it is seen in many big US cities, external, including New York, Miami, Chicago and Los Angeles.

So why has the capital's population continued to grow despite so many people leaving? It can be explained by two factors.

The first was its birth rate: 790,000 more people were born in London than died between 2009 and 2017.

The second factor was international immigration. There was an increase of 860,000 between 2009 and 2017, with more than half coming from the EU. By 2017, 3.6 million people living in the city were born overseas.

Of the Britons moving to the capital, a look at their ages reveals a great deal.

A large number of people move to London in their 20s, drawn from all corners of the country.

This is because of the range and number of job opportunities that the capital offers.

But among almost every other age group, the capital sees more people leaving than arriving.

This is most pronounced for very young children, people aged 18-20 and people in their 30s.

A look at where people move to after leaving the capital offers an insight into why this happens.

Young families form a wave of people leaving the capital

The 18-20 age group spreads out across the country, especially going to cities such as Nottingham, Coventry and Brighton. The most common reason is to start university.

It is safe to assume the other age groups - the children up to four years old and the 30-somethings - are leaving together. Paddington train station isn't full of unaccompanied toddlers with their suitcases.

These are the young families moving out of the capital, very often in search of homes for less than London's notoriously high prices.

Yet this does not mean that they are giving up on London altogether and returning "home" to the other parts of the country they first moved from.

Unlike people moving for university, many stay within commuting distance.

Two-thirds of these age groups remain in what might be called "the Greater South East" - an area stretching from Southampton up to Milton Keynes and across to Norfolk.

So while they no longer live in the city, they still have the option to work there.

And the 800,000 people who commute into London each day - more than the entire population of cities such as Leeds and Bristol - suggest that many of them do.

Among those Londoners who remain past their 30s more continue to leave than arrive, albeit in smaller numbers.

These flows of people - the arrival of large numbers of young people and the departure of many of those who are older - also explains why London is such a young city.

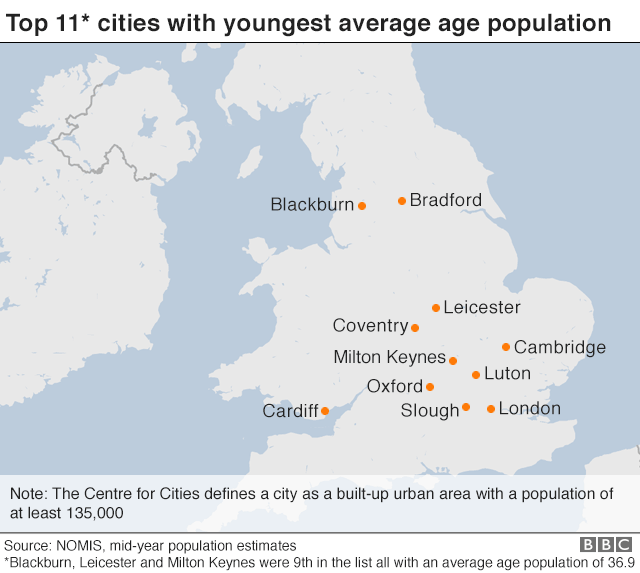

With an average age of 37, its population is the sixth youngest of any large town or city in the UK. Oxford, Cambridge and Coventry all have populations with an average age under 36, while in Swansea and Sunderland, the oldest, it is 41.

London's experience differs to other big British cities.

Places like Liverpool, Sheffield, Newcastle and Nottingham have also seen their population and economies grow. But the waves of people arriving and leaving are very different.

They see two waves of people leaving - one for those aged 21-30 (many of whom head to London) and a second for people aged over 30.

The inflow and first wave of out-migration is related to universities.

These cities have a number of universities in them and attract many thousands of students from across the country, including London.

But many of these students leave the cities behind as easily as they moved to them once they graduate.

Taking Liverpool as an example, it sees an inflow of people aged 18-20 from almost every other city in England and Wales. But the opposite trend is seen for 21 to 30-year-olds, with the city losing more of this age group to almost every other city than it gains.

However, it is crucial to note that some of these students do stay on.

In the case of Liverpool, one in five of the students who move to the city for university make it their home after graduation. And so the number of highly qualified young people living in the city increases overall.

But like London, these big cities also experience a second wave of people leaving when they hit their 30s.

And like the capital, these people don't move very far, once again looking for somewhere for their families to live.

For example, people leaving Birmingham tend to head for places like Shropshire or Staffordshire. And people leaving Newcastle mainly move to neighbouring Northumberland and County Durham.

These patterns show that different places offer different things to people as they get older.

The vibrancy and job opportunities offered by our biggest cities appeal to students and young professionals. This shapes these cities in terms of the shops, bars and other facilities they offer.

But among older residents, the desire for things like more space and a less urban environment grows, and many move out.

It reminds us that cities are not islands, with residents flowing in and out of them depending on their stage of life.

With it comes the challenge of making sure there is the right type of housing where people want to live and the transport to get them about.

About this piece

This analysis piece was commissioned by the BBC from experts working for an outside organisation.

Andrew Carter is chief executive and Paul Swinney is director at the Centre for Cities, which describes itself as working to understand how and why economic growth and change takes place, external in the UK's cities.

This piece uses data from the ONS on England and Wales's 58 largest urban areas. Comparable data is not available for Scotland and Northern Ireland.

Edited by Duncan Walker