How long will the undercover policing inquiry take?

- Published

In February 2019, one of the UK's longest-running and most controversial inquiries confirmed what's been long suspected - that it may be another year before it hears any evidence at all.

The inquiry into alleged undercover policing abuses, external was launched four years ago, in March 2015.

It was supposed to have reported in 2018 - yet as it passes another anniversary, it has still not resolved some of the fundamental questions about how it should hear and publicise evidence.

Given that it won't hear any before 2020, it won't remotely get to the full facts before the 10th anniversary of the unmasking in 2011 of Mark Kennedy, one of the officers whose actions led to miscarriages of justice.

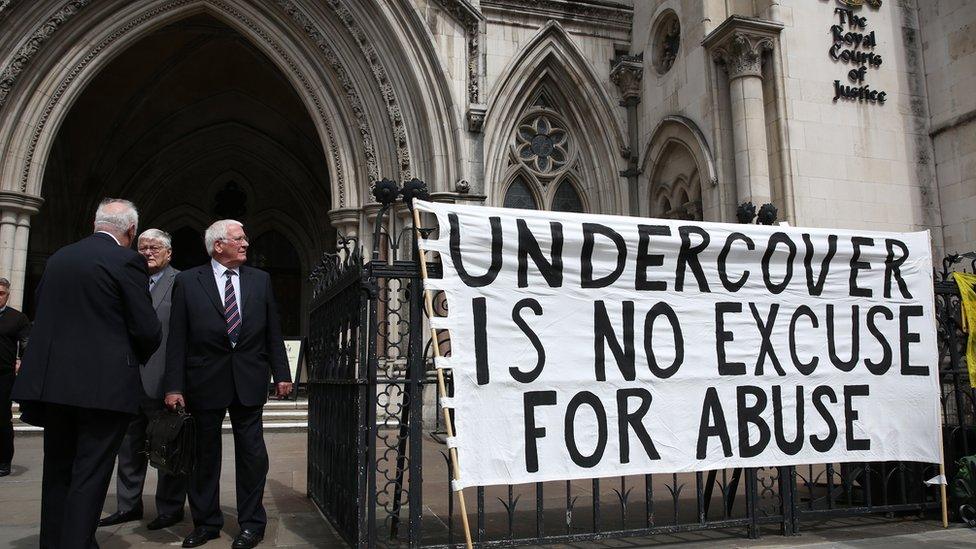

Victims have walked out of court in protest at how the inquiry is being run, a move backed by Baroness Lawrence, the mother of Stephen Lawrence who was murdered in 1993.

It was the allegation that an undercover officer had infiltrated the Stephen Lawrence justice campaign that triggered the inquiry.

Police officers who thought they had been promised lifelong anonymity have threatened not to co-operate.

And amid all of this, it has spent £13m trying to navigate a legal and logistical quagmire relating to anonymity, national security and privacy.

The key objective of the inquiry is to get answers from the officers who made up two disbanded units - the Metropolitan Police's Special Demonstration Squad (SDS) and the National Public Order Intelligence Unit (NPOIU).

Of the more than 160 former SDS officers who are still alive, more than 100 have sought some form of anonymity - and two-thirds of those have got it.

Baroness Lawrence backed the victims' walkout

An even greater proportion of the more than 60 NPOIU officers are expected to be similarly protected because many of them are still serving in the police - and potentially still undercover.

This anonymity process - we'll have the final figures by the summer - has been at the heart of complaints from the victims of abuses.

They say that unless campaigners who were targeted know who the officers were, they cannot provide meaningful evidence to the inquiry.

Lawyers for the officers argue that undercover officers are entitled to anonymity because their lives may be in danger - although in some cases the pleas are simply based on concerns about privacy.

The story of the officer codenamed HN16 shows how difficult this exercise has been.

HN16 was in the SDS and infiltrated groups between 1997 and 2002. In his anonymity application he said some of his targets were violent.

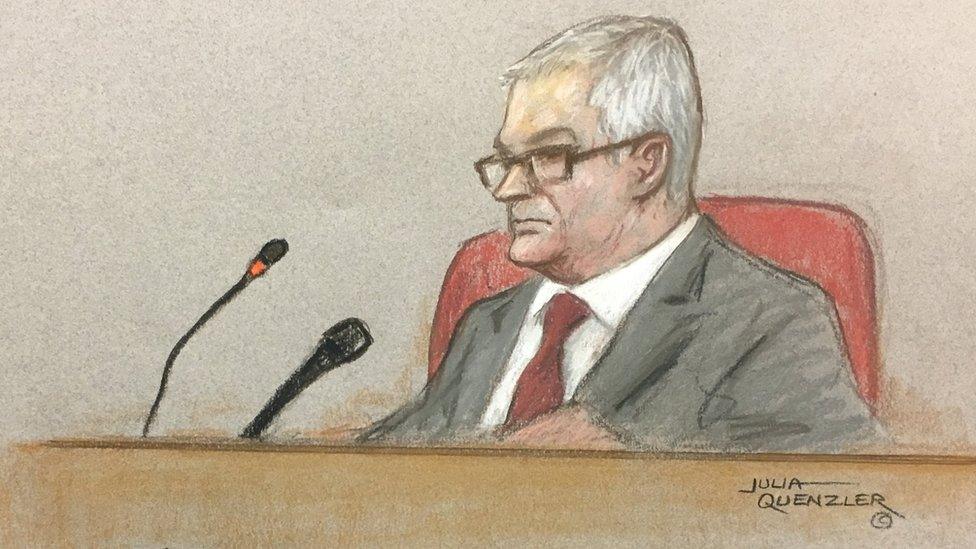

Now the ruling from Sir John Mitting, the inquiry chairman, is that he won't be named unless there is a good reason to do so - despite campaigners saying that he won't know what the good reason is unless the officers are named.

In the case of HN16 he came to a halfway-house position.

Sir John Mitting, a retired judge, is heading the inquiry

In late 2017, he disclosed the officer had infiltrated the Animal Liberation Front and hunt saboteurs in Croydon and Brixton, south London. And he'd used two cover, or fake, names: James Straven and Kevin Crossland.

The latter was the name of a real five-year-old boy, who died in an air crash in August 1966.

When it came to building his undercover identity, HN16 apparently obtained Kevin's birth records, and created a fictional life by legally resurrecting a boy who had died in an awful disaster.

This "stealing" of the names of dead children is one of the major limbs of the inquiry. And revealing HN16's cover name led to him being implicated in a second strand.

Two women came forward to say the officer had tricked them into sexual relationships. They're known as "Ellie" and "Sara" - false names attributed to them to protect their right to anonymity.

HN16 has now admitted both relationships. Their stories came to light only when there was enough information about the officer for them to join the dots.

The upshot is that the chairman has declared that HN16 will have to be named, despite his protests.

Former undercover police officer Mark Kennedy spent seven years living as environmental activist Mark Stone

How long did this process take? Three years to reach a final position. And it will be a lot longer before we hear from HN16 about why he did it.

If the suspected victims can't know the names of all of the officers who were monitoring them, will they find the truth lies in the reports those officers filed?

Here, the second challenge the inquiry faces becomes clear.

Scotland Yard has described the process of tracking down and assessing undercover documents dating back to the late 1960s as "unprecedented".

There are now 100 police officers and staff working full-time on helping the inquiry - and a further 30 lawyers and legal staff advising them.

Scotland Yard couldn't give the BBC an up-to-date figure, but their last estimate was that the inquiry was now costing £14m a year.

But there's more.

The National Police Chiefs Council (NPCC), the umbrella group for chief constables, is also involved.

It has uncovered the data equivalent of 40 million pages of records relating to the National Public Order Intelligence Unit's activities.

Now, clearly, a lot of those pages will be irrelevant, but what if just 1% of the documents are important?

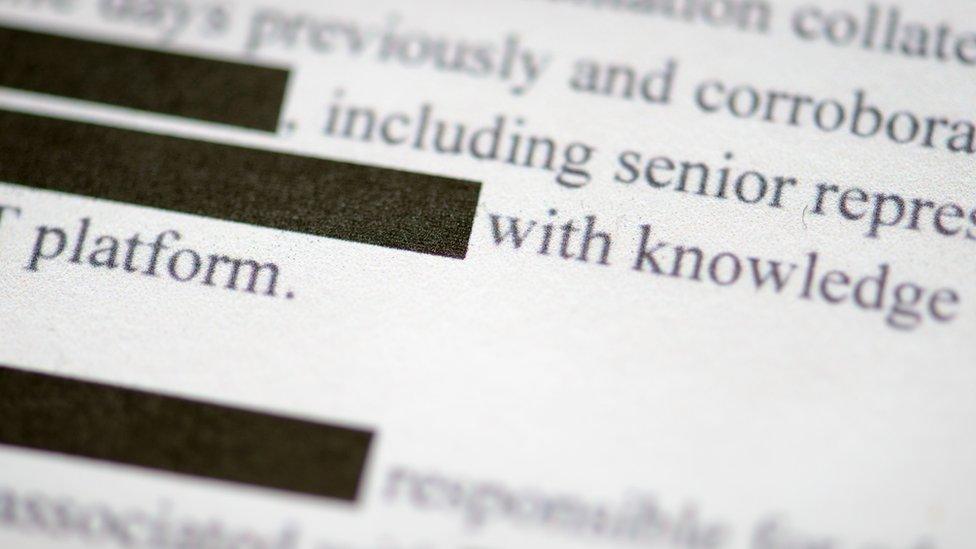

The NPCC thinks it could take a team of officers more than four years to go through them to assess whether they need redacting (censoring) before being disclosed to the public.

The vast numbers of documents involved is one of the inquiry's main challenges

And as the inquiry limbers up to record the officers' actual accounts about their undercover lives, the strain to manage all this information - and work out what can safely be put in the public domain - will only increase.

The NPCC predicts the total costs across all forces will be in the tens of millions of pounds.

There is also now a new and bewilderingly complex issue of the right to privacy.

On Monday 25 March the inquiry holds the second of two complicated hearings into the handling of personal information about the people officers targeted.

Let's say the inquiry has an intelligence report from Officer HN16 on an animal-rights meeting he watched. That report would name attendees, what they said and did, and who they associated with.

Should the inquiry reveal those details - to the officers - and should these documents be heavily redacted before the public see them? If they're redacted, they won't make much sense: it will be difficult to understand who was being targeted - and why.

The inquiry wants to show uncensored reports to the officers, so it can ask them to justify their actions. But the inquiry may have a legal duty under data protection laws, as the custodian of this historical document, to ask the individuals first what they want retained by the inquiry - and therefore disclosed.

Helen Steel is concerned that private information about victims will be made public

At the inquiry's last major hearing in January, Sir John Mitting revealed that based on 26,000 documents from the decade up to 1984, SDS officers each produced 1,000 pages of intelligence reports.

In total, they gathered information concerning around 5,000 people.

When one of the lawyers for victims suggested the inquiry contact all of the 5,000 to give them the same opportunity to seek anonymity and privacy as the officers, Sir John replied: "We will not finish this decade."

Helen Steel, who was tricked into a relationship, said it would be "absolutely outrageous" to deny victims the chance to withhold sensitive personal information. In her case, she has already discovered enough to be sure that information about her health made it into the files.

"It feels like entirely double standards," she said.

"We have had three years of hearings about protecting the police and their privacy and fears, and now effectively it feels like we are being told it is too great a burden to protect the privacy of those who were actually spied on, who have already had their privacy invaded by the state."

So these are just some of the monumental challenges the inquiry still has to resolve.

Will it be the UK's longest inquiry? It would have to run for 13 years and three months to beat the record (which concerned investigations into hospital deaths), according to the Institute for Government. So if I'm still watching it in 2028, I'll let you know...

- Published8 March 2019

- Published15 February 2018