Mother’s Day: From medieval brawls to greeting cards and flowers

- Published

Mother's Day has not always been about flowers, chocolates and dutiful children - the history of the day is full of conflict and controversy.

The story of Mother's Day is a tale of two women.

Neither had any children of their own. One was inspired by medieval traditions with a surprisingly dark side, while the other grew to regret she ever suggested the day.

If you take the advice of the latter, this Sunday, you wouldn't even send a card. Greetings cards are for the lazy. A more earnest show of appreciation would involve giving a cake.

Mother's Day or Mothering Sunday?

If you're reading this in the US (or Australia, Canada or dozens of other countries), don't panic. Your Mother's Day isn't until the second Sunday in May.

The UK, however, marks the day on the fourth Sunday of Lent - 31 March this year - thanks to its revival of a medieval tradition called Mothering Sunday. But it took an American to give us the idea.

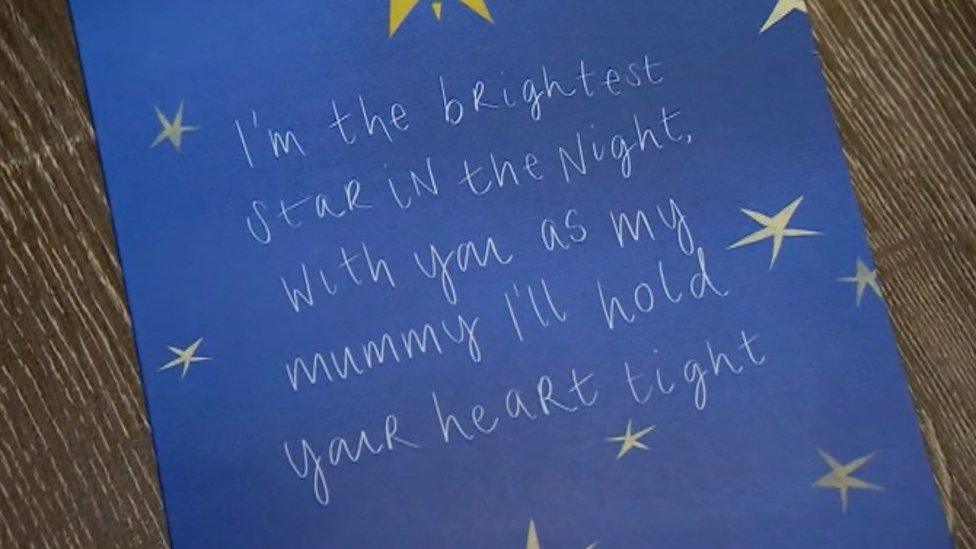

A printed card means nothing except you are too lazy to write to the woman who has done more for you than anyone in the world

Anna Jarvis, of West Virgina, is the matriarch of modern Mother's Day. She organised the first in 1908, following the death of her own mother. By 1914 the US president had proclaimed it a national holiday.

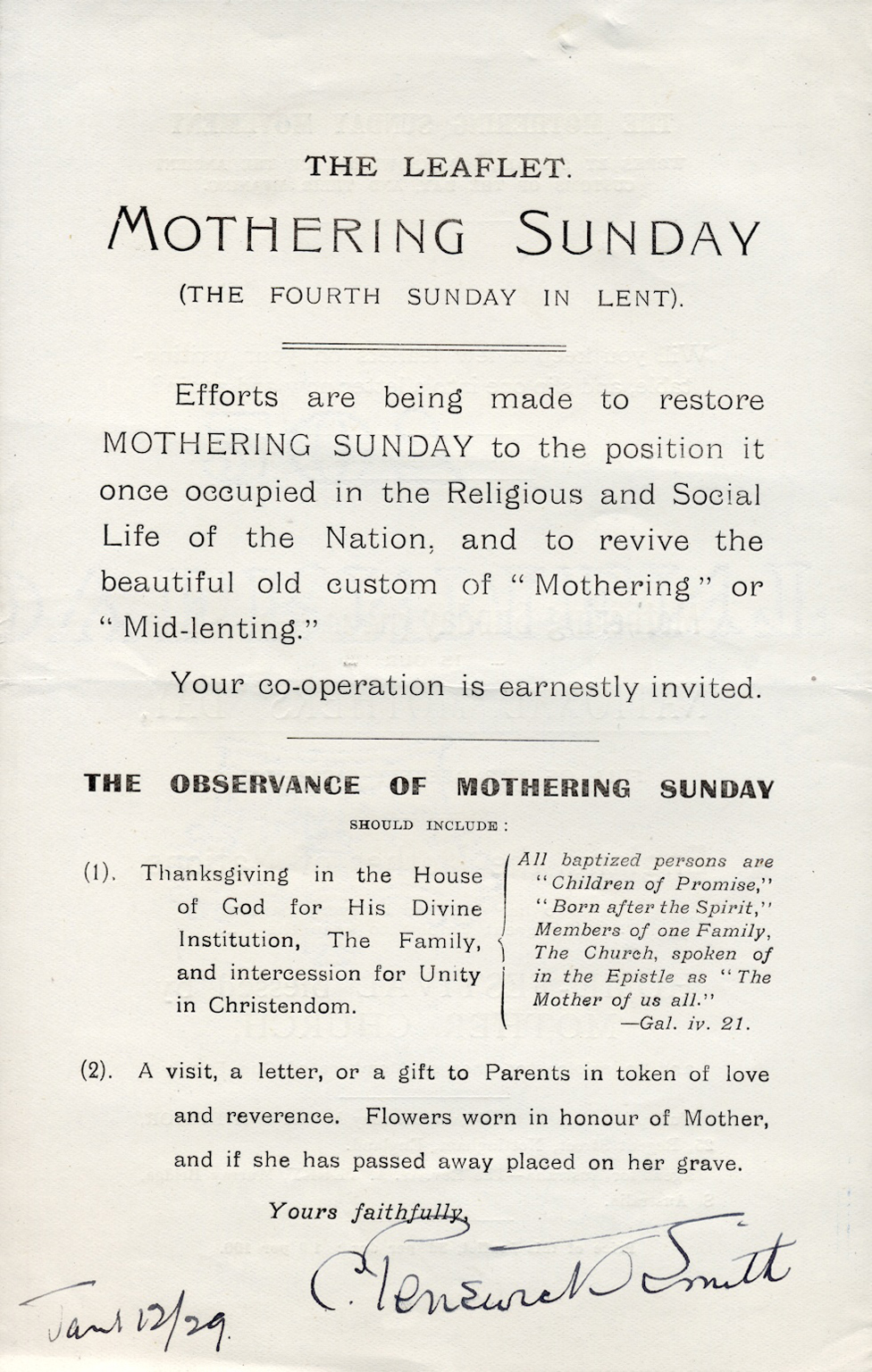

A British woman, Constance Adelaide Smith, was inspired by this success. But she was also afraid of an American celebration displacing British traditions, and so campaigned to bring back its medieval incarnation instead.

"A lot of people felt that industrialisation and urbanisation were destroying British culture and community," says Cordelia Moyse, a historian who writes about women and the Church.

Ms Smith was part of a wider trend in the early 20th Century that idealised what it saw as the greater social harmony of medieval England.

'Too lazy'

Pilgrimages to the "mother church" or cathedral were the focus of the medieval Mothering Sunday.

However, these ancient traditions weren't quite as peaceful and unifying as Ms Smith believed. Parishes often got into brawls over who should go first in the procession. A 13th Century bishop of Lincoln had to threaten punishments because of these fights.

Over the years Mother's Day simnel cakes became elaborately decorated confections

A later custom of live-in apprentices and domestic servants going home to visit their mothers, which started in 17th Century Gloucestershire and Worcestershire, also inspired Ms Smith's Mothering Sunday revival.

But these visits had a very practical purpose, says Prof Ronald Hutton, an expert in British ritual history at the University of Bristol.

"It was one of the leanest times of the year, when food stocks were at their lowest," he says. Young people would check up on their families and bring food or money if they needed it.

That's why one tradition of Mothering Sunday was the simnel cake. Named after the medieval word for fine flour, it was originally boiled and then baked. But by the 19th Century, it had become a saffron-hued fruitcake decorated with marzipan.

Either way, it proved an easy means of bringing calorie-dense food to hungry parents.

Flowers and cards were later additions to the celebrations. Anna Jarvis encouraged the wearing of white carnations, her mother's favourite, in honour of the day.

But she soon resented the commercialisation of her idea, calling for boycotts of florists, gate-crashing a confectioners' convention and even getting arrested for disorderly conduct at one of her protests.

She reserved perhaps her greatest scorn for greetings cards.

"A printed card means nothing except that you are too lazy to write to the woman who has done more for you than anyone in the world," Ms Jarvis said.

Today many people are concerned that those who have lost their mother or parents who have lost a child can feel hurt and left out by the celebrations.

But the adoption of Mothering Sunday in Britain may also have been driven by grief.

The historian Cordelia Moyse says the celebration was given official support during World War One and gained increasing public acceptance when the war ended.

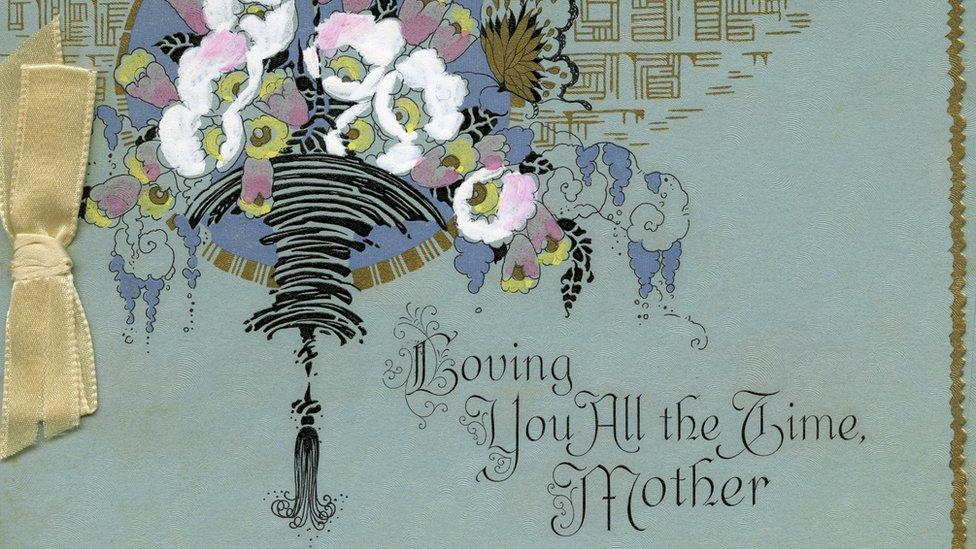

A mother's day card from the 1910s, condemned by the holiday's founder as only for the "lazy"

"It's hard not to see it as partly a reaction to the British First World War experience and the great loss of life," she says.

By the time Constance Smith died in 1938, Mothering Sunday was said to be celebrated in every parish in Britain and every country in the empire.

In the US, Anna Jarvis's ambivalence about what she had created turned to regret. By 1943, she was so concerned at the commercial takeover of her holiday that she got together a petition to rescind Mother's Day.

People didn't listen, however, and she died penniless five years later in the Marshall Square Sanitarium in Philadelphia.

By this point it was clear who had won the battle over commercialisation: Her bills were paid by the floral and greetings card companies that she had campaigned against.

A leaflet promoting Mothering Sunday, signed by Constance Adelaide Smith under her pen name, C Penswick Smith

- Published11 March 2018

- Published27 March 2019

- Published26 March 2019