Why UK child poverty targets won’t be met

- Published

Twenty years ago, then Prime Minister Tony Blair pledged to end child poverty in a generation, at a speech in central London.

He called it a "20-year mission". Two decades and three prime ministers later, BBC Reality Check looks at what has happened to child poverty.

What counts as poverty?

If someone asked you what poverty was, you might think about how far someone's pay packet goes. Can they afford their household bills? Can they ever go on holiday?

But rather than looking at how someone is making ends meet, the main way poverty is assessed is by using a relative measure - "relative poverty".

It's calculated by taking the median income in the country - that's the midpoint where half of the overall population have income more than that amount and half have less. It was £507 a week in 2017-18, external, or £437 after housing costs.

Then you take 60% of this middle amount and anyone who has less income than this is considered to be living in relative poverty.

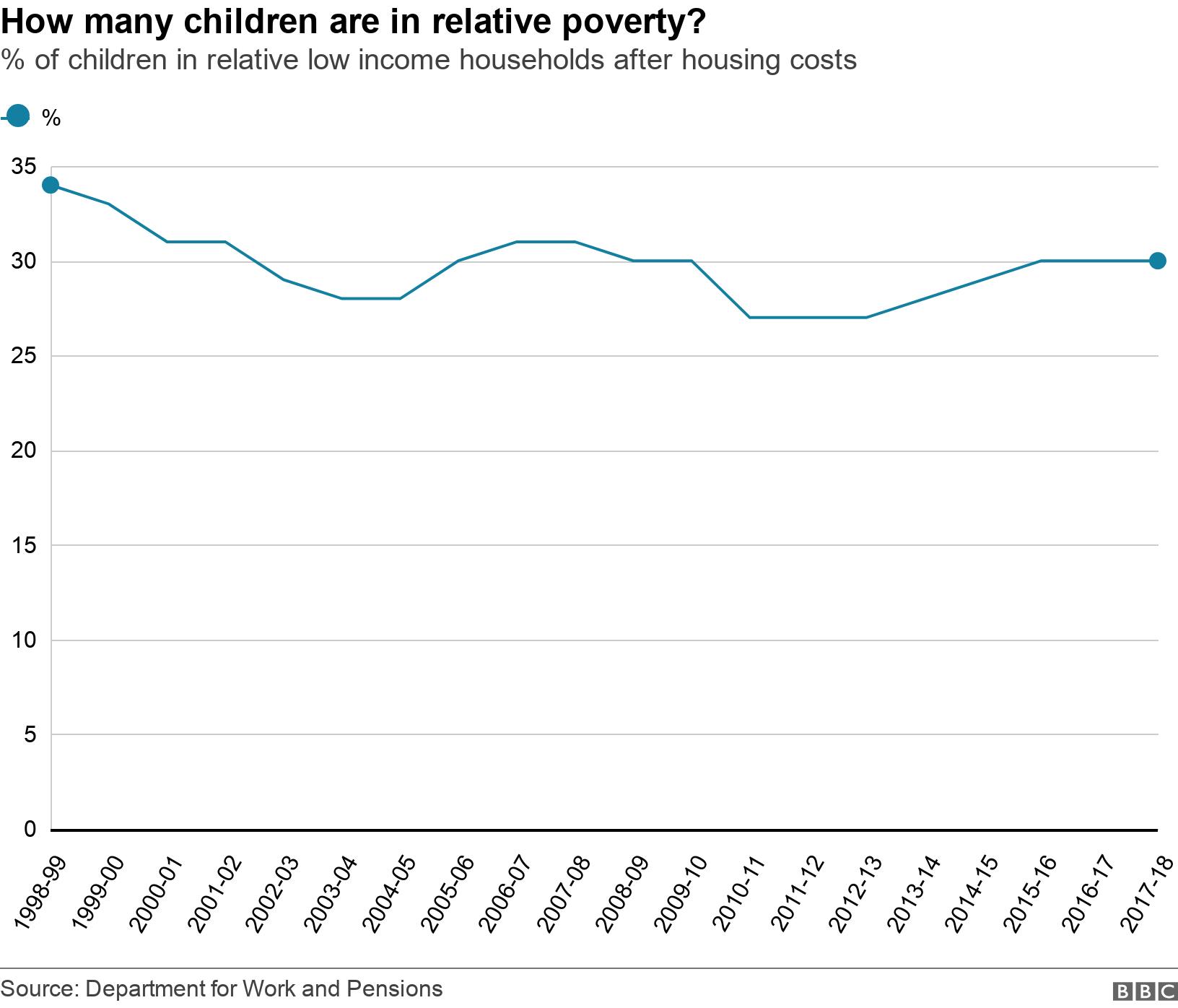

In 1998-99, 34% of children in the UK were living in relative-poverty households.

Today, this proportion is 30%, which represents about 4.1 million children.

Statistics on income after housing costs and benefits received are more widely used as this gives a better idea of how much disposable income someone might have.

But, some say relative poverty is flawed as a measure because the poverty line moves when average income changes.

In times of recession, for example, when lots of people's wages decrease, relative poverty rates improve.

That's because the gap between the median and lowest incomes is less but low-income families might not be any better off.

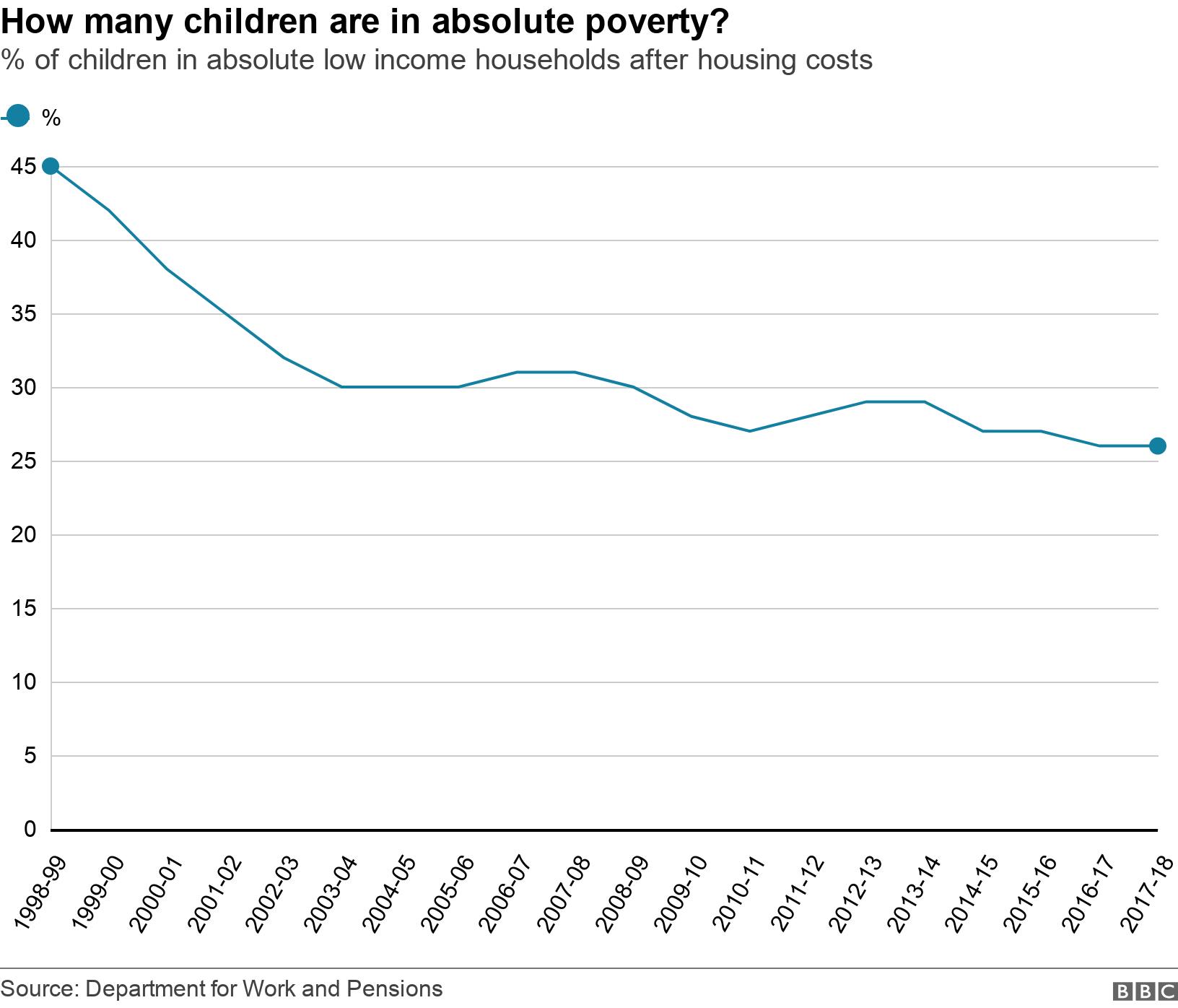

Figures are also published on "absolute" poverty.

Instead of comparing people's incomes with the average for the current year, these use a fixed year - 2010-11 - to track how many people have been in poverty over an extended period of time.

This can help avoid the problems of a drop in incomes in one year changing the poverty line.

But absolute poverty doesn't reflect how, if standards are rising quickly for the rest of society, the poorest are being left behind - because it is fixed on a middle income from almost a decade ago.

On this measurement, the number of children in poverty has reduced more quickly, falling to 26% in 2017-18.

Analysis by Robert Cuffe, BBC head of statistics

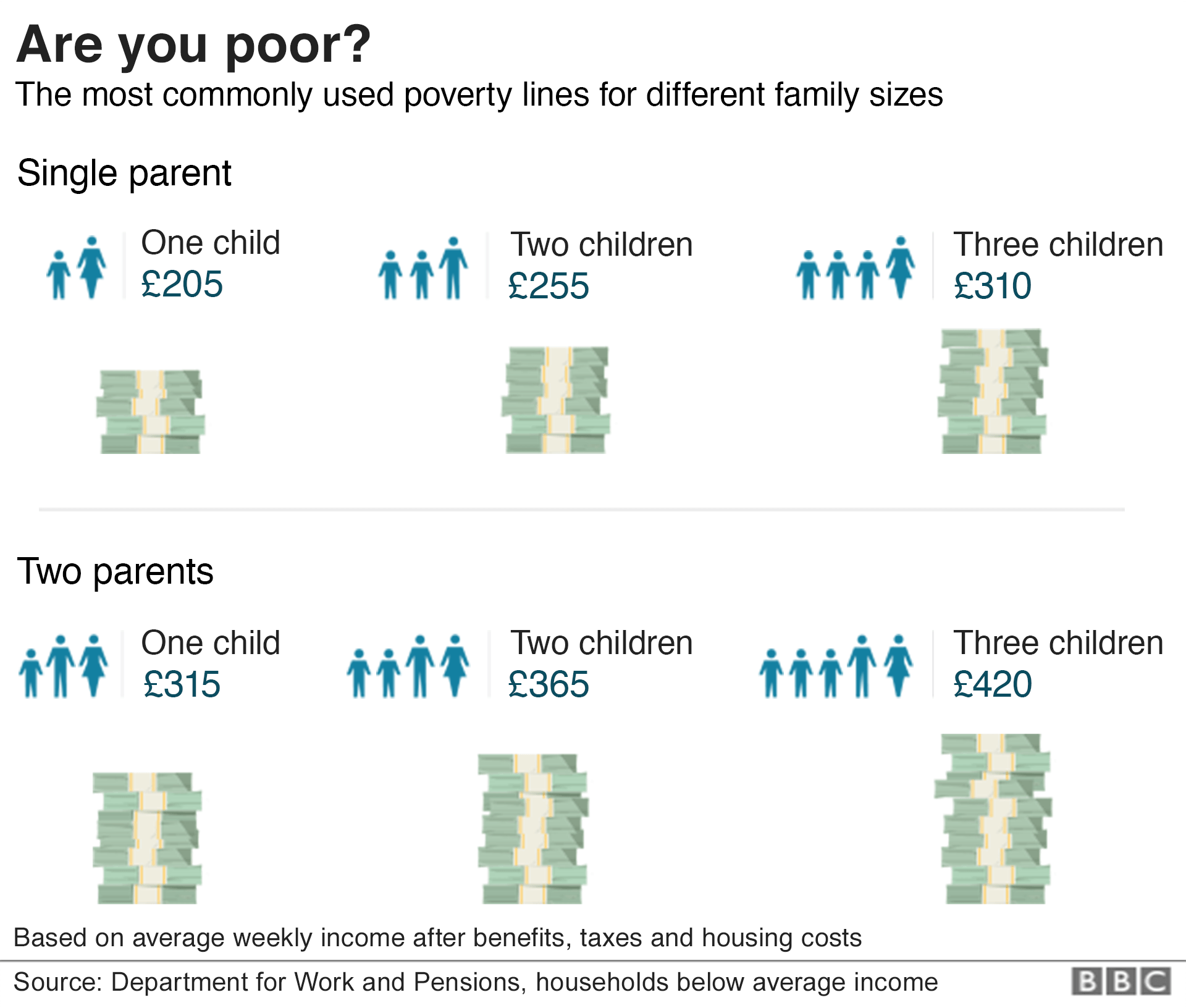

With many different definitions of the poverty line, it's easier to understand what they mean by looking at pounds and pence.

Here's what the version you'll hear most often from politicians, analysts and campaigners - relative poverty - means in real money.

A one-child-one-parent family is poor unless they have more than £200 a week left to spend after paying their tax and housing costs.

For a two-parent-two-child family, it's £360.

That's not the dollar-a-day often referred to when talking about global poverty.

In a rich country such as the UK, it's more about whether someone can do what all the people around them do and still make ends meet.

In 2016, the Conservatives removed poverty targets established by Labour in 2010.

The government said basing policies on "relative" poverty simply led to efforts to push income above the poverty line rather than tackling the underlying causes of poverty.

Labour's targets were also based on incomes before housing costs were accounted for.

Attempts have been made to agree an alternative measure of poverty - whether their income meets the material needs of a family, such as affording a bedroom for every child over 10 and a school trip once a term.

Record high

Meanwhile, the proportion of children living in relative poverty risks hitting a record high by the end of the Parliament, according to the Resolution Foundation.

In a recent report, external, the research group said it was projected to rise to 37% by 2023-24.

The foundation blames economic factors and government policy.

It said a spike in inflation in 2017 and weak wage growth for lower-paid workers have put pressure on household budgets.

Speaking to BBC News last year, Mr Blair said that efforts to reduce child poverty required a "new approach" to infrastructure, housing and investment in new technologies, saying these would help reduce wage stagnation.

Child Poverty Action Group director of policy Louisa McGeehan said: "By 2021, we will be cutting £40bn a year from our work-and-pensions budget through cuts and freezes to tax credits and benefits and, as a result, we have put so much progress on child poverty into reverse."

She also cites cuts to universal credit and the two-child cap on benefits as contributing to poverty rates.

This week in the House of Commons, Prime Minister Theresa May said the government is taking poverty "very seriously".

She added: "The only sustainable way to tackle poverty is with a strong economy and a welfare system that helps people into work."

Since becoming Work and Pensions Secretary, Amber Rudd has attempted to soften some benefit cuts introduced under the government's austerity programme, including removing the two-child cap on universal credit for some families.

- Published25 March 2019

- Published4 March 2019

- Published11 February 2019