Labour poverty pledge: What does it mean?

- Published

Labour has said it will end in-work poverty within its first full term if it wins the next election.

People in working families are much less likely to be living in poverty than those where no-one is in work - but working poverty has been rising in recent years.

While 17% of children in a family where someone worked were living in relative poverty last year, that soared to 56% where no adult in their household worked.

But, as Labour has pointed out before, most children in relative poverty are in households where someone works. That's because most households work, so they make up a greater share despite being relatively less likely to be in poverty than those children in workless households.

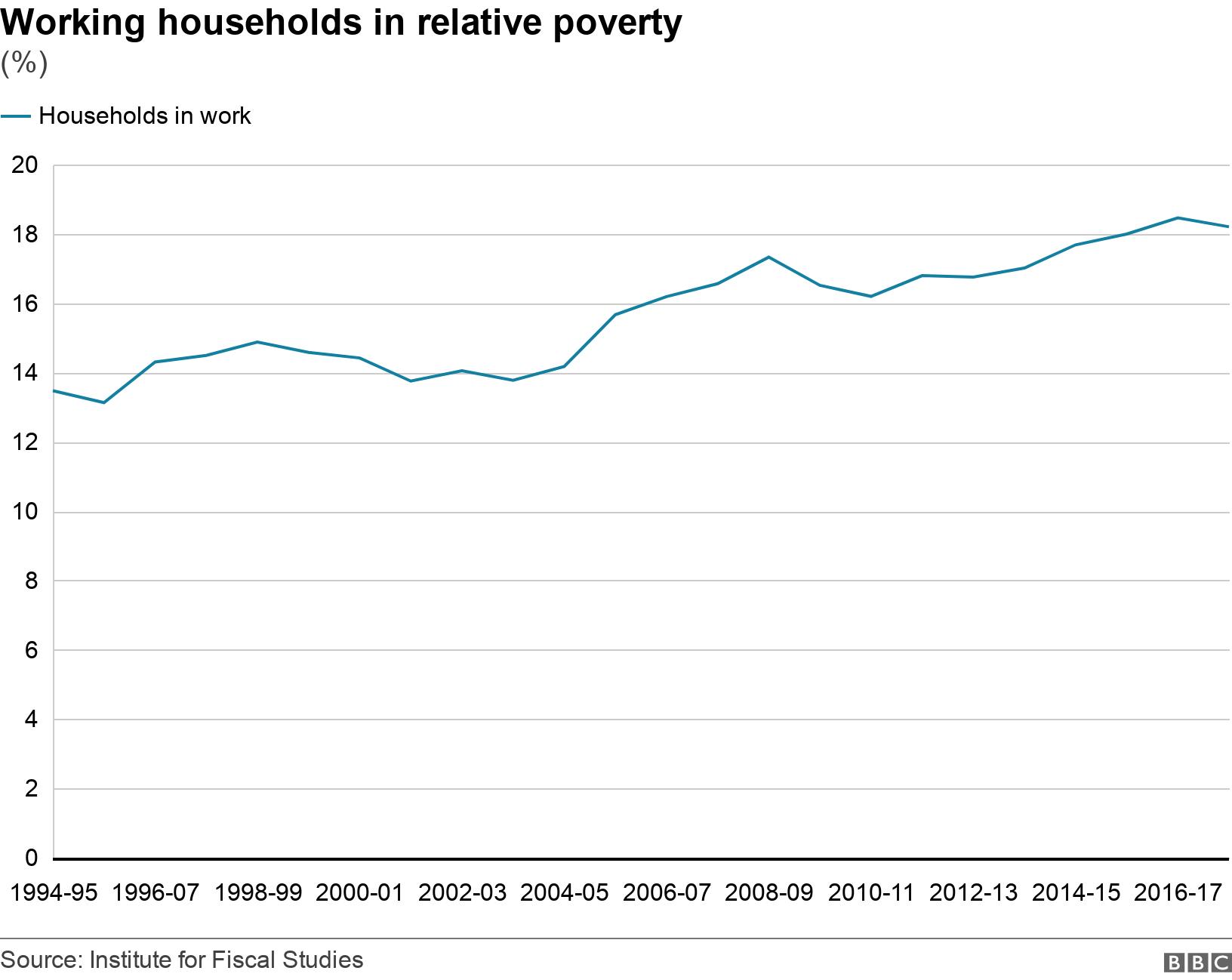

Between 1994 and 2017, the proportion of people in working households in relative poverty rose from 13% to 18%, according to the Institute for Fiscal Studies (IFS) - eight million people in 2017.

Although this has partly been driven by stagnating wages and rising housing costs, it also reflects how many more people are in work.

"They are better off than they would have been had they stayed out of work - but they remain in poverty," the IFS says.

When we talk about how many people are in poverty today in the UK, first we need to know how we define it.

Currently, when the government talks about poverty, it uses either a measure of relative poverty - that is, how someone is doing financially compared with the rest of the country - or absolute poverty.

To establish whether someone is living in relative poverty, the government looks at the median income - that is the midpoint where half of the working population earn more than that amount and half earn less. Then they take 60% of this middle amount and anyone who earns less than this is considered to be living in relative poverty.

According to the Joseph Rowntree Foundation (JRF) charity, that's an income less than:

£248 a week for a couple with no children

£144 a week for a single person with no children

£401 a week for a couple with two children aged between five and 14

£297 a week for single parent with two children aged between five and 14

When government talks about absolute poverty, it does the same calculation but uses the median income in 2010-11 to give a constant measure over time.

While relative poverty tells you about the gap between low and middle-income households, absolute poverty is a good measure of how much the living standards of low-income households have changed over time.

You can also look at these measures either before or after housing costs.

The JRF says it favours the relative measure after housing costs since rising rents and property prices are a growing contributor to poverty.

What's been happening to poverty?

Absolute poverty, both before and after housing costs, has halved over the past 20 years.

But while absolute poverty is falling, the reduction over the past 10 years was much smaller than it has been over comparable periods of time since the 1960s.

Relative poverty, meanwhile, has remained more or less stagnant - inequality is as bad as it was two decades ago.

How good are these measures?

No single measure of poverty will give you all the information, but looking at these measures gives a pretty good picture of what's going on.

One problem with using relative income is that, in times of recession when lots of people's wages suffer, inequality may appear to improve as the poorest are protected through benefits and tax credits - but they are not actually any better off.

Absolute poverty tells you whether people are staying the same relative to other people or getting left even further behind.

But how people are faring compared to the society they live in is the internationally recognised standard of measuring poverty.

'Normal life'

Loughborough University publishes a minimum income standard which it considers to be a good measure of how much money someone needs to participate in normal life in the UK.

While this is not a measure of poverty, it tries to capture changing social norms - for example internet access may previously have been a luxury, but now a school-age child living in a house without internet access could be significantly disadvantaged when it comes to completing homework.

In 2016, the university's Centre for Research in Social Policy said single people needed to earn at least £17,100 a year (£329 a week) before tax, and couples with two children at least £18,900 (£363 a week) each to achieve the minimum income standard.