Legal dilemma of granting child killers anonymity

- Published

Angela Wrightson suffered terribly at the hands of her young killers

The High Court is to decide whether a ban on identifying the killers of Angela Wrightson should remain in place now that they have reached the age of 18.

The two women were aged 13 and 14 when they tortured and murdered Angela Wrightson, 39, in her Hartlepool home in December 2014.

She suffered more than 70 separate slash injuries and 54 blunt-force injuries in a seven-hour attack.

Neither teenager was named at the time, because as juveniles they were granted anonymity by the court. So in what circumstances have child killers been granted anonymity?

What the law says

Children appearing in youth or crown courts in England and Wales, whether as a victim, witness or defendant - cannot be identified if they are under the age of 18, apart from in exceptional circumstances.

The older of Angela Wrightson's killers was encouraged to use drawing as a way to channel her anger. This picture was found in her room after her arrest

The European Convention on Human Rights enshrines the right to privacy and a family life - so once they have served the sentence for their crimes they have the right to move on.

Exceptional circumstances refers to a pressing social need where the public interest outweighs the interest of the child - this is rare and usually only happens in high profile cases.

Emily Setty, a lecturer in criminology at the University of Surrey, thinks the public want children to be identified because such violent crimes challenge society's ideas of what it is to be a child, and to try to understand what went wrong.

She said: "In these very, very shocking cases, it's disturbing to think that children are capable of such crimes, so we like to say they were born evil so we can separate them from our own children."

She argues that this was the case with Jon Venables and Robert Thompson, who were named.

The killers of James Bulger

Jon Venables and Robert Thompson were 10 years old when they kidnapped, tortured and murdered two-year-old James Bulger in 1993.

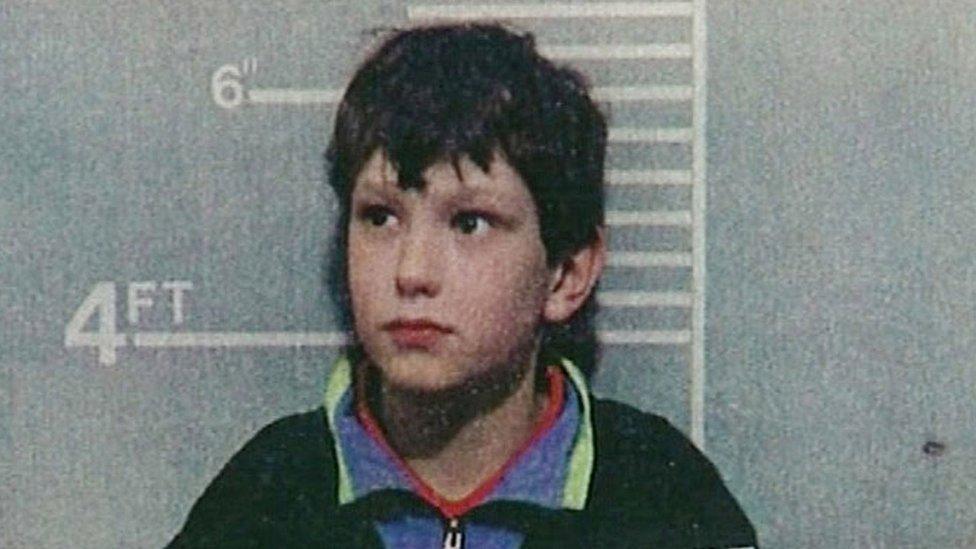

Jon Venables (left) and Robert Thompson were both aged 10 when these photos were taken

The trial judge lifted reporting restrictions, saying: "The public interest overrode the interest of the defendants."

He argued there was a need for an "informed public debate" on crimes committed by young children.

In 2001, Venables and Thompson were granted new identities and life-long anonymity when they were released on licence.

A court order banned anyone from revealing their new identities.

James Bulger's father, Ralph Bulger, asked for information about Venables' new identity to be made public when he was jailed for possessing child abuse images.

James Bulger’s mother Denise Fergus says she does not want Venables' identity to be revealed

Mr Bulger lost that legal challenge and Sir Andrew McFarlane, president of the family division of the High Court, said the order was designed to protect the "uniquely notorious" Venables from "being put to death".

A 'clear deterrent'

In 2014, a High Court judge lifted the restrictions on naming Will Cornick, a 16-year-old who murdered his teacher, Ann Maguire.

Will Cornick was named by the judge "in the public interest"

Mr Justice Coulson said identification was in the public interest and would have "a clear deterrent effect".

Outlining his decision, he said: "Ill-informed commentators may scoff, but those of us involved in the criminal justice system know that deterrence will almost always be a factor in the naming of those involved in offences such as this.

"There are wider issues at stake, such as the safety of teachers, the possibility of American-style security measures in schools, and the dangers of 'internet loners' concocting violent fantasies on the internet.

"I consider that the debate on those issues will be informed by the identification of William Cornick as the killer."

Frances Cook, of the Howard League for Penal Reform, was one of those who criticised naming Cornick.

She said: "The child will be notorious inside prison and will never be able to grow past the crime he committed. The crime is now his permanent identity.

"Public knowledge about the child also brings with it identification of his wider family, who in their way are also victims."

The right to move on

Mary Bell was 11 years old, external when she was convicted of manslaughter after killing two small boys, aged three and four, in 1968.

Mary Bell, who was convicted in 1968, now has a new identity

She was named during the trial but was given a new identity and anonymity when she was released in 1980 and the judge made it clear this would not set a precedent for any other cases, which are judged on an individual basis.

In 2003, Bell was given a fresh identity to protect her daughter until she turned 18, and a High Court judge later granted life-long anonymity to both Bell and her daughter, external - after she discovered her mother's past years later when tabloid papers tracked them down.

The new court order was granted in an attempt to protect Bell and her daughter from potential vigilantes.

Social media and anonymity

Social media further complicates reporting restrictions as many people are not aware of the law and it is much easier to find and share information.

Actress Tina Malone was given a suspended prison sentence last March after she breached an injunction protecting the identity of James Bulger's killer Jon Venables.

There is a global ban on publishing anything about the identity of Venables or his accomplice Robert Thompson, but Malone shared a Facebook message which was said to include an image and the new name of Venables, a court heard.

Tina Malone avoided jail after she admitted breaching an injunction protecting the identity of Jon Venables

Malone claimed she was not aware she had done anything wrong, even though she understood Venables had been given anonymity for his protection.

Two months earlier Richard McKeag, 28, and Natalie Barker, 36, were given suspended sentences after admitting posting photos they claimed identified Venables.

Should child criminals get life-long anonymity?

In 2016, a government-commissioned review said child criminals should be given life-long anonymity.

Pippa Goodfellow of the Standing Committee for Youth Justice, said anonymity is an important part of the rehabilitation of children who offend - and naming them as adults, especially in the age of social media, "makes it very difficult for them to put their past behind them".

She told the BBC: "If a child who had turned their life around was identified upon reaching adulthood and labelled 'an offender', this could have disproportionately negative affects on their relationships, education and employment opportunities."

Ian Murray, executive director of the Society of Editors, said it was a "very complicated issue" and although the media should "recognise that there is a chance for young people to reform", there should be some form of public enquiry, with all the necessary agencies involved, to decide on individual cases whether it is in the public interest for them to be named.

He said: "The public, and the family of victims, need to know they are getting anonymity for all the right reasons."

- Published29 December 2016

- Published26 February 2019

- Published31 January 2019

- Published26 March 2019

- Published25 January 2019

- Published3 November 2014