Why blend? Exploring the art and science of blending

- Published

Humans are the blending species, says philosopher of the senses Barry Smith, but what makes some blends work when others don't? What does the skill of a good blender consist in? And is blending an art or a science?

Whether your favourite drink is tea or coffee, champagne or Scotch whisky, you may be surprised to learn that what you're drinking is probably a blend. Whisky lovers often prize single malt whiskies more highly than the blended Scotch that combines them, but even single malts will be mostly blends of spirits from different casks.

The urge to blend, it seems, is everywhere, and it is also a distinctly human act. We alone go in for these repeated experiments of combining what is known and familiar to create something new, and this marks us out as the blending species.

The blending of words and phrases to express new thoughts, like the blending of sounds to create music, provide examples of a productive process in which we generate novel experiences by rearranging recognisable parts into previously unencountered wholes, and it is this process that makes blending fundamental in our creative ingenuity.

A teabag may contain 35 different teas

When did the human urge to blend first appear? It is hard to put a date on it but the blending of flavours in teas or aromas in perfume has been with us for as long as we've known these products and the seemingly inexhaustible possibilities of creating new fragrances and new blends of teas continues apace.

A blend is a combination of ingredients mixed together to produce something unique and distinctive and the success of a blend lies in its ability to unite separate elements into a seamless whole - or, a harmonious and unified arrangement of parts.

Find out more

Listen to The Art and Science of Blending from Monday to Friday this week at 13:45 on BBC Radio 4

The first episode, on whisky, is available online now

The greater the number of elements, the harder it is to achieve overall balance and harmony, where all the parts make a contribution and no one element dominates the others. It may surprise you to learn that in a bottle of Johnnie Walker Black Label whisky there can be as many as 30 single malts in the blend, mixed together with grain whisky.

What is more astonishing still is that from year to year the blenders must attempt to reproduce the sought-after flavour of Black Label even though the malt whiskies they use to blend are in a different condition each year - and even when some of those malts may be unavailable. This is the skill of the blender: to aim at the same thing each time while ingredients change from year to year.

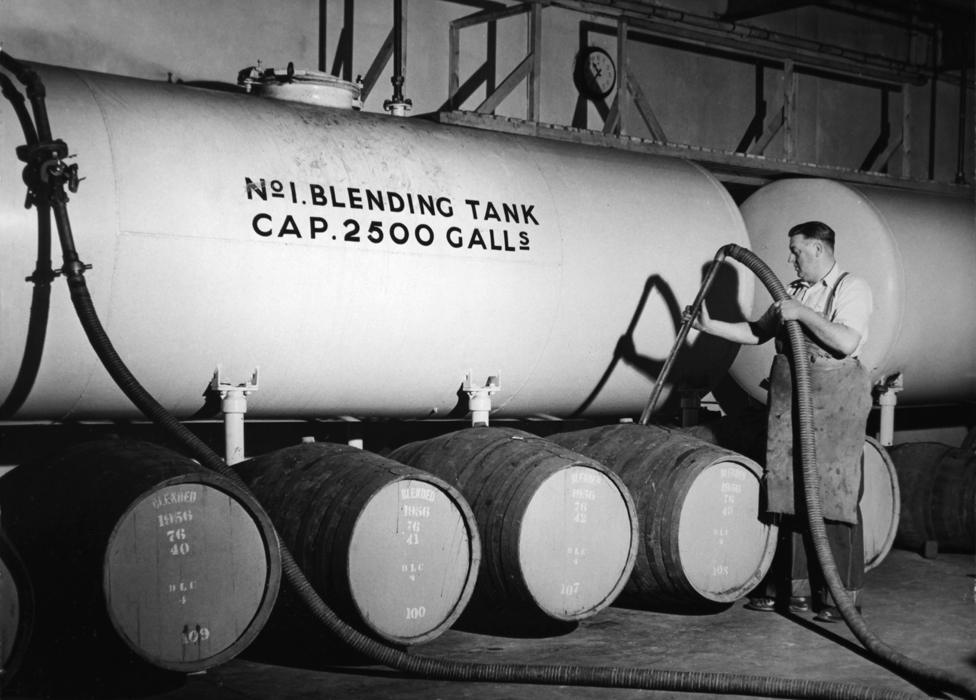

Blending Drambuie in Edinburgh, 1940

It is the same story with champagne. Veuve Clicquot's Yellow Label wine is a blend of more than 450 wines, made from different grapes - Chardonnay, Pinot Noir and Pinot Meunier - picked from different vineyards, combined with reserve wines made in previous years that have evolved with time.

This famous blend depends on place, time and type of grape variety, to which are added the carbonated bubbles produced by a second fermentation of the wines in the bottle, making champagne perhaps the ultimate blended product.

The secrets of blending are built up through a lifetime of experience. Perfumers know when two aromas will stay separate and when they will fuse to become a single new based on the proportions we combine. These combinations of notes, known as an "accord" - the French word for chord - which in turn becomes yet another ingredient to go into the blend.

The art is knowing which mixtures are likely to work, which combinations of scents will fuse - and not confuse.

The blending room in a French champagne vineyard

We still don't understand the science behind this merging of compounds into a single, unified aroma. Is it something about the chemistry of these volatile substances, or, more likely, is it a characteristic of our olfactory equipment that our noses treats some collections of molecules as a single note and others as a diverse collection of odours?

A single molecule, such as benzaldehyde, can smell like a mixture of cherry and almond, whereas collections of more than 800 molecules can smell like a single thing, coffee. The neuroscience of olfaction has several unresolved mysteries concerning the way we code and smell odours, which is why no artificial nose can yet predict which arrangements of scents we will experience as a whole let alone which ones we will find agreeable. For now, at least, the blending of aromas and flavours still relies on art as well as science.

But why blend in the first place? Why not stick to the best quality ingredients without combining them?

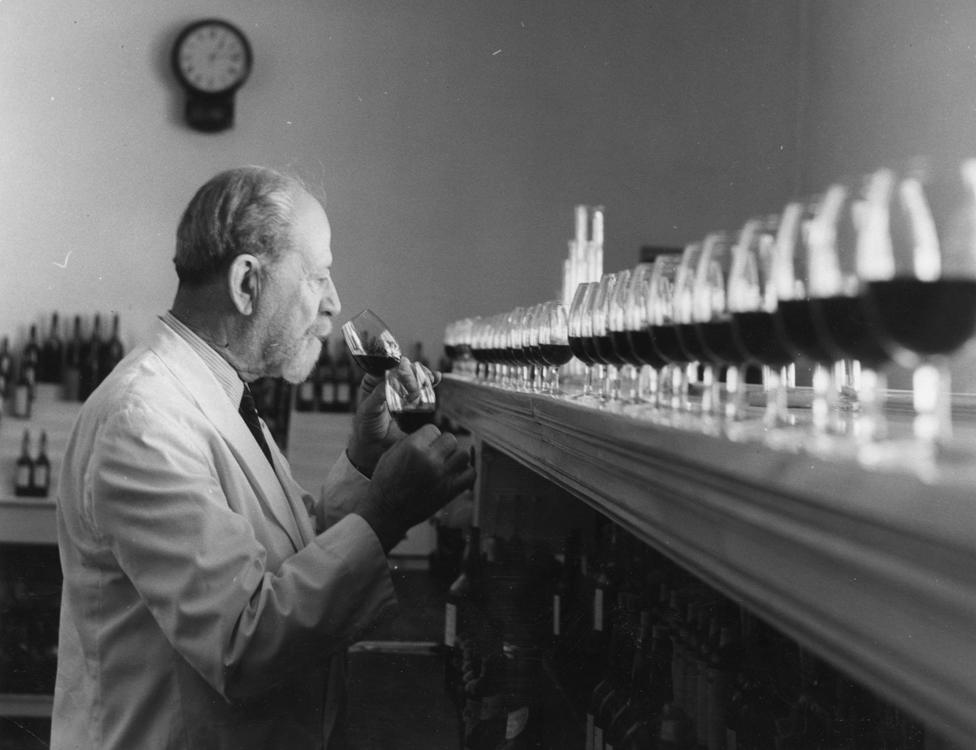

Tasting and blending Gonzalez Byass sherry in 1954

The urge to blend has been opposed by an equally strong urge for purity. There are passionate advocates of single-leaf teas, single-cask malt whiskies and single-vineyard champagnes, who argue that only here will we find true quality.

The thinking behind the straining for purity is all about origins. The direct line back to a single source ensures that nothing has been lost or adulterated. Unfortunately, we sometimes encounter the same line of thought when it comes to the mixing of races or cultures. Opposed to this is cosmopolitanism, which says it doesn't matter where we come from, it's all about fitting in. Is this the right view?

Philosopher Kwame Anthony Appiah is suspicious of the search for purity and he points out that hardly any of the things we care about in the domain of culture fit that model.

"Shakespeare wouldn't have been very interesting if he'd said, 'I can't write a play about Hamlet because he's a Dane,'" he says.

"Basho wouldn't have been much of a poet in Japan if he had said, 'I can't use Buddhism and I can't use this Chinese script to write my poetry, so I can't write haiku.'

"It seems to be the natural condition of music and literature and so on to want to borrow and mix and rethink in order to make new things."

At the same time Appiah is keen to stress that the importance of origins has been unduly neglected by some cosmopolitans.

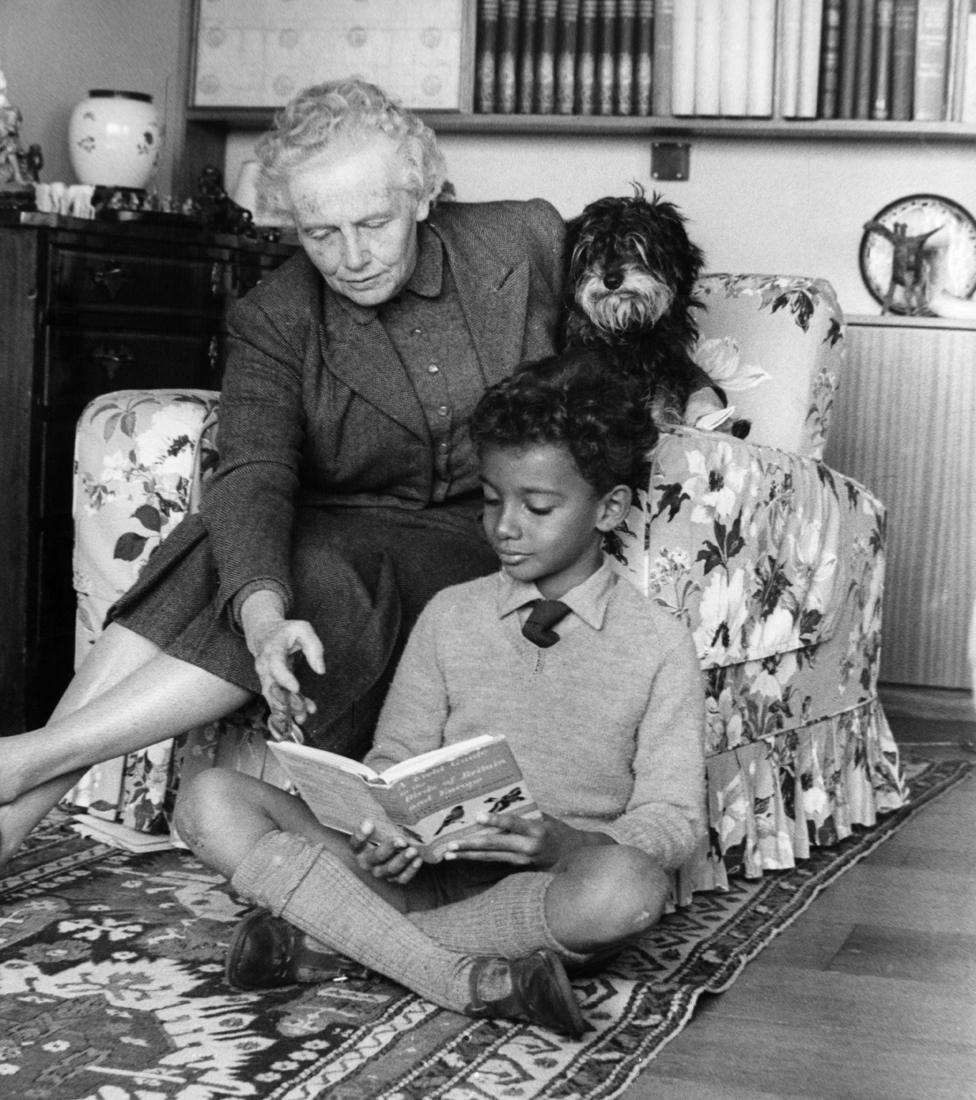

Kwame Anthony Appiah with his Gloucestershire grandmother in 1962

"I like what Gertrude Stein said about this. She said, 'What good are roots if you can't take them with you?' And I think all of us in fact can claim connection back down many branching routes through the family tree to many different places," he says.

"I grew up in two places and each of them was very different from the other - one was a village in Gloucestershire and the other was the second largest town in Ghana. And I am pleased to be able to connect myself to both of those places both by ancestry and by experience. I wouldn't want them not to be different from each other; there wouldn't be anything additive about it, if they were to become the same."

Stories of origins are important to most of us, and perhaps we can all agree that it's what's in the mix that matters - but also how well it's blended.

Prof Barry C Smith is director of the Institute of Philosophy at the University of London's School of Advanced Study, and the founding director of the Centre for the Study of the Senses

You may also be interested in:

Craig from Guinness World Records measures the Jaffa Cake

It's a delicious structure consisting of a small sponge with a chocolate cap covering a veneer of orange jelly. It is arguably Britain's greatest invention after the steam engine and the light bulb. But is a Jaffa Cake actually a biscuit, asks David Edmonds.

Read: Cake or biscuit? Why Jaffa Cakes get philosophers very excited

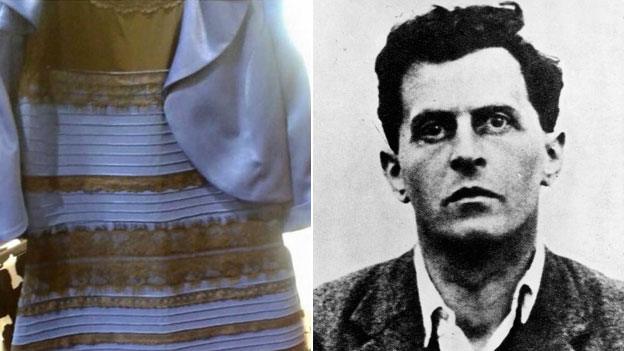

We all assume that we see what's before our eyes, and if we have normal colour vision we should be able to tell what colour the dress is. And yet we've just discovered that the world of observers divides into two groups - those who see the dress as white and gold, and those who see it as blue and black, or blue and olive green. They know they are looking at the same image and that it isn't changing, so why is there such marked disagreement about how the dress looks?

The English language contains an alphabet soup of swear words. Those of a sweary disposition can draw upon the A-word, the B-word, the C-word, the F-word, the S-word, the W-word and many more. So here's a puzzle - if you see the F-word spelled out with all four letters, are you more offended than when you read F with asterisks?