Why do so few rape cases go to court?

- Published

MPs have called on the government to do more to support rape victims

There has been a "completely unacceptable" collapse in rape prosecutions in England and Wales despite a record number of cases, MPs say.

The Home Affairs Committee has called for more funding for prosecutions and better support for rape victims

What do the figures show?

Police in England and Wales recorded 67,125 rape offences in the year to December 2021 - the highest recorded annual figure to date.

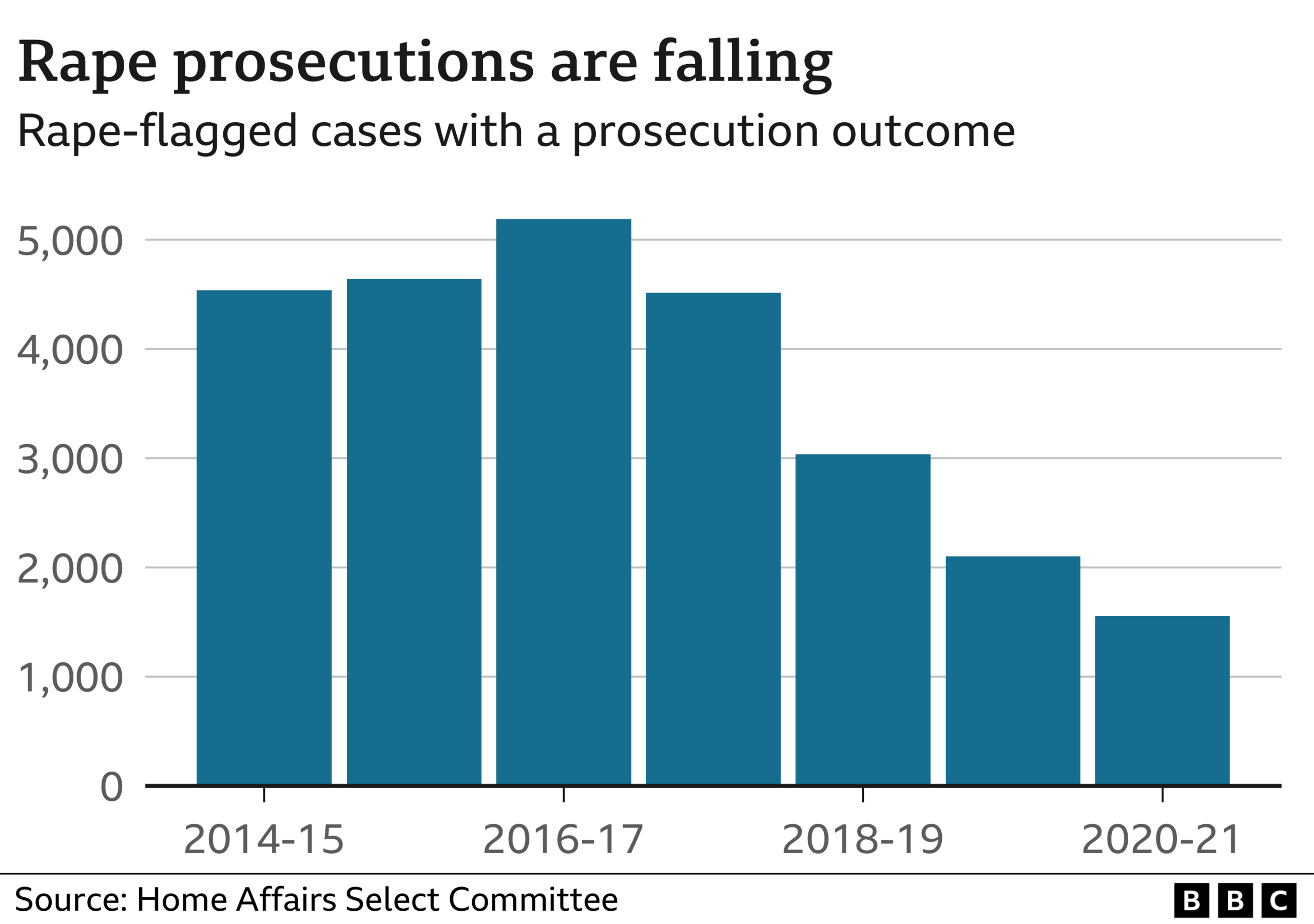

In 2020-21 there were just 1,557 prosecutions, compared with 2,102 in the previous 12 months.

Over the past four years, rape prosecutions in England and Wales have fallen by 70%.

From the point that a crime is reported to the police, to a decision being made in court, there are a number of hurdles to be overcome. At each stage, cases are dropped.

As a result, rape prosecutions represent a small percentage of all reported rapes. And an even smaller proportion lead to a conviction - when someone is found guilty.

So, what is going on?

Gathering evidence

The police have to gather enough evidence in order to refer a case to the Crown Prosecution Service (CPS) - the body that conducts criminal prosecutions in England and Wales.

But there has been an increase in the amount of evidence to consider - often from phones and social media.

This has made these cases more difficult for police, prosecutors and - in many cases - victims.

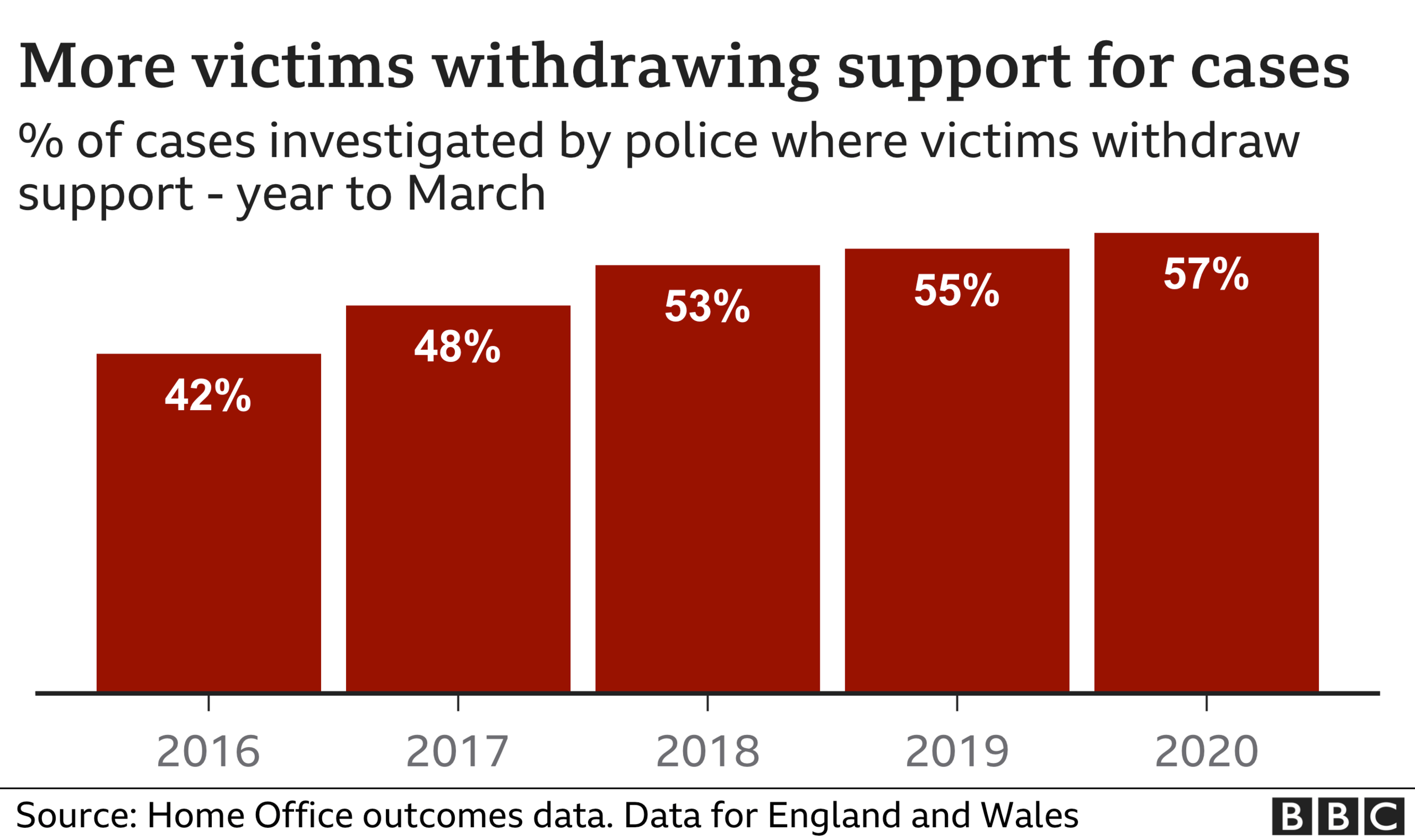

Victims' Commissioner Dame Vera Baird said some victims withdraw their complaints after being asked to hand over their phones so that data can be downloaded: "They cannot face the unwarranted and unacceptable intrusion into their privacy."

The Home Affairs Committee heard from victims who said that if they had known how long their case would take, they would not have "brought the case to the police's attention in the first place".

In May 2022, the government announced new rules in an Annual Review of Disclosure, external, which aim to reduce the intrusion into victims' lives during criminal investigations.

For example, police and prosecutors now have to present written justification for gathering personal information about rape victims, such as phone messages and therapy notes.

Getting to court

Once a case is referred by the police, the CPS decides whether there is enough evidence to charge a suspect with a crime. Only after this can it go to court.

In the year to September 2021, just 1.3% of rape cases recorded by police resulted in a suspect being charged (or receiving a summons). This compares to a 7.1% charge rate for all other recorded crimes in the same period.

The CPS has been bringing fewer rape prosecutions over the past few years, which is partly due to fewer referrals by police. This is thought, in part, to be a reaction to a fall in the number of successful convictions.

The 2020 victims' commissioner's report says: "Some police officers say the reason they made fewer referrals was precisely because they knew that CPS were prosecuting fewer cases."

In November 2019, it was also revealed the CPS had previously had a secret conviction rate target, introduced in 2016 - that 60% of rape cases should end in a conviction. It was suggested this may have led prosecutors to drop weaker or more challenging cases. The target was dropped in 2018.

In 2018, the Director of Public Prosecutions, Alison Saunders, stepped down after several rape cases collapsed due to evidence not being disclosed to the defence.

In Scotland, there were 300 prosecutions for rape and attempted rape in 2019-2020, external. This was an increase of 20% from 2016-17. Despite this, just 43% of prosecutions led to a conviction according to the latest statistics.

In the past year in Northern Ireland,, external 76 suspects were prosecuted for rape, which is an increase of 19% from 2016-17.

Funding cuts

In June 2021, then Justice Secretary Robert Buckland was asked whether government cuts were a factor in low prosecution rates.

He said: "Like all parts of public service, big choices were made in the last decade, because of the position that we all faced economically and that's, I think, self-evidently the case."

The Institute for Government estimated, external that the budget of the CPS was cut by 28% between 2009-10 and 2018-19 after adjusting for inflation.

CPS staff numbers fell too:

In 2010/11, there were 8,094 full-time equivalent CPS staff in post

In 2020/21 there were 5,419 full-time equivalent CPS staff in post

Support for victims

In February 2022, the Ministry of Justice (MoJ) announced a package worth £40m, external to support victims of crime.

Several parts of the funding are for women and girls affected by sexual violence:

£1.3m to allow victims to access support remotely

£16m to recruit more independent sexual violence and domestic abuse advisers

£20.7m for community-based sexual violence and domestic abuse services, aiming to lessen the amount of time survivors have to wait for support

Some charities feel that the government is still not doing enough for victims of sexual violence.

Jayne Butler, of victims' charity Rape Crisis, says: "The criminal justice system is categorically failing rape victims and survivors, and steps from the government to rectify the situation lack ambition - they must do more."

This piece was originally published in April 2019, but has been updated to include the latest statistics. It was altered on 24 June 2021 to clarify that the CPS is not funded as part of the Ministry of Justice.