UK terror threat: How has it changed?

- Published

The terrorist threat to Britain is radically different today from what it was at the outset of the Islamic State group's caliphate five years ago, according to senior Whitehall officials.

While the threat from far-right extremism and dissident Irish Republicans has grown substantially, officials believe that IS has lost one of its major appeals - that of a physical territory with which to attract recruits from Europe and elsewhere.

The threat to Britain from international terrorism is still judged as severe, external.

That is the second highest out of a list of five, as assessed by the Joint Terrorism Analysis Centre (JTAC) which makes its recommendations independent of government.

It has been at that level or higher since August 2014 and means that a terrorist attack is judged to be highly likely.

And counter-terrorism police and MI5 are currently handling over 700 investigations, a record number.

The Security Service, MI5, has more than 3,000 subjects of interest (SOIs) on its watch list, more than it is capable of monitoring around the clock, as well as a pool of over 20,000 former SOIs, some of whom are thought capable of moving to violent action.

While those numbers always seem to only move one way - upwards - the threat has changed dramatically over the last five years and there is some good news.

Although far right extremism and dissident Irish Republican activities are on the rise, Whitehall officials say that today it is much harder for IS to draw recruits from Europe as it no longer rules over a physical territory - which it called a caliphate - after IS fighters lost their last stronghold at Baghuz in Syria in March.

British jihadists are no longer travelling in numbers and with ease across the Turkish border into Syria, as they were five years ago.

In Britain last year there were fewer arrests and plot disruptions than in 2017.

Fewer plots are reaching the late stage of planning. Yet for some, the propaganda appeal of both IS and al-Qaeda lives on.

MI5 says that 80% of the plots disrupted by western intelligence agencies last year involved people inspired by violent jihadist ideology yet who had no contact with its leadership in the Middle East.

Emergency services at the scene of the Westminster attack in 2017

The enduring appeal of that propaganda online remains a major concern, especially when it comes to lone actors, not part of any network, who keep their plans to themselves.

Since the collapse of the caliphate this spring there have been some lurid headlines in the media about IS "crocodile sleeper cells" lying in wait to strike in various European countries.

So how real is the threat?

There is no question, say Whitehall officials, that hitting back at all the Coalition countries that crushed them remains an aspiration for what remains of IS's leadership.

"If they could mount an attack here they would," said one.

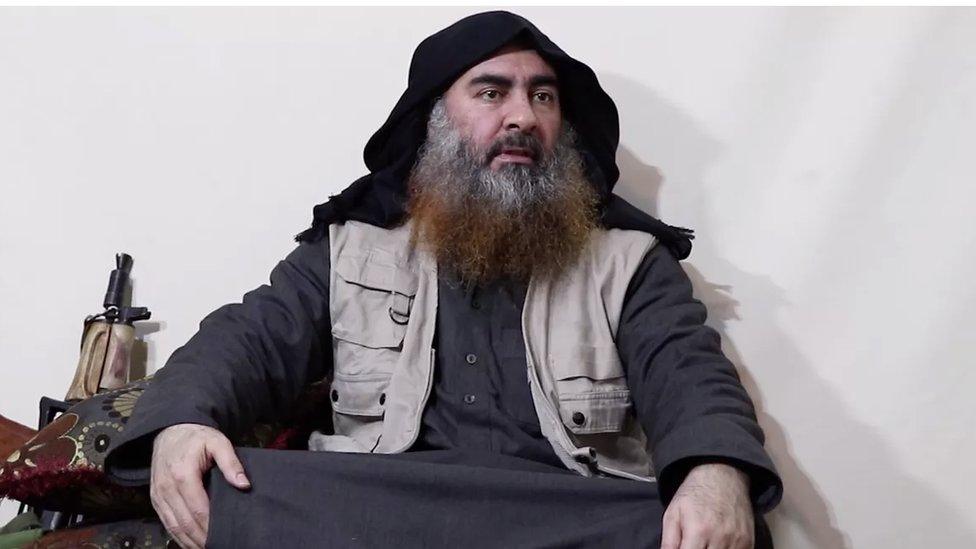

But those few senior IS leaders who have survived, including Abu Bakr Al-Baghdadi who appeared recently in an online video, are thought to be geographically dispersed and heavily preoccupied with avoiding death or capture.

Senior IS leader Abu Bakr Al-Baghdadi, who appeared recently in an online video

Perhaps more worrying than the fugitive leadership is the concentration of IS fighters and their often highly radicalised dependants in refugee camps in Syria.

More than 60 British detainees are believed to be in various camps across eastern Syria.

There is a risk this could provide an ideal networking capability for surviving IS operatives in the same way as the US-run Camp Bucca in Iraq in 2004 provided the perfect incubator for IS's future leadership.

Al-Qaeda, meanwhile, has not disappeared.

The organisation co-founded by Osama Bin Laden that carried out the infamous 9/11 attacks in 2001 has watched and waited from the sidelines as the IS caliphate disintegrated, just as it predicted.

IS's use of graphic, online violence and gratuitous cruelty attracted large numbers of international recruits, many with criminal records and psychopathic tendencies, during its heyday in the period 2013-16.

But this extreme violence also alienated many potential recruits, people who al-Qaeda are now appealing to join its ranks.

The group's main problem has been that its nominal leader, an obscure, bookish Egyptian doctor, lacks charisma.

But if Bin Laden's son Hamza adopts that mantle, that could change overnight.

- Published1 August 2019

- Published19 March 2019

- Published18 February 2019

- Published3 January 2018