Probation service: Offender supervision to be renationalised

- Published

The supervision of all offenders on probation in England and Wales is being put back in the public sector after a series of failings with the part-privatisation of the system.

It reverses changes made in 2014 by then Justice Secretary Chris Grayling.

The National Audit Office said problems with the part-privatisation had cost taxpayers nearly £500m.

All offenders will be monitored by the National Probation Service from December 2020.

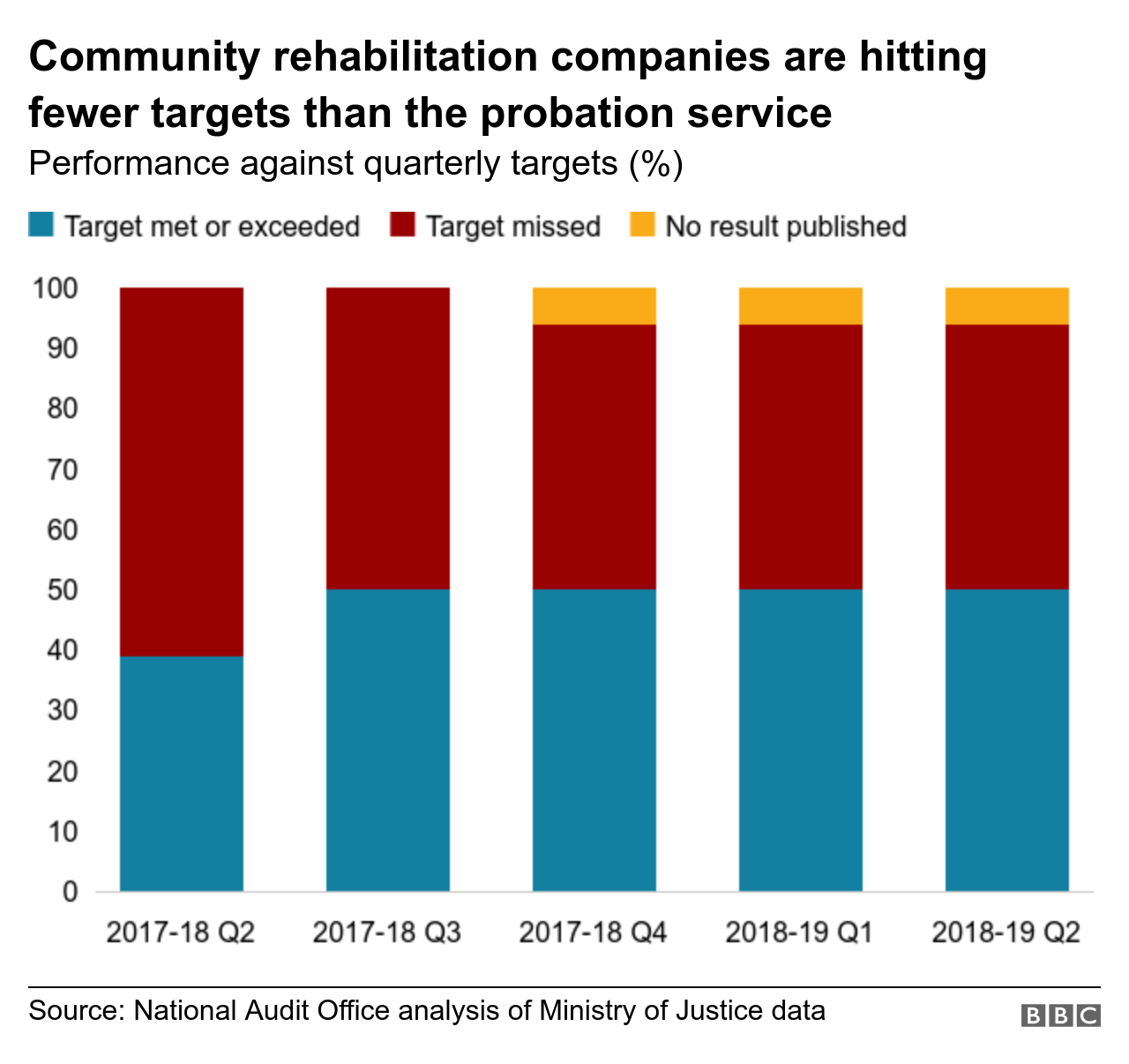

It had previously been managing just those posing the highest threat, with low and medium risk offenders monitored by community rehabilitation companies.

Chief probation inspector Dame Glenys Stacey said she was "delighted" about the decision because the model of part-privatisation was "irredeemably flawed", and people would be safer under a system delivered by the public sector.

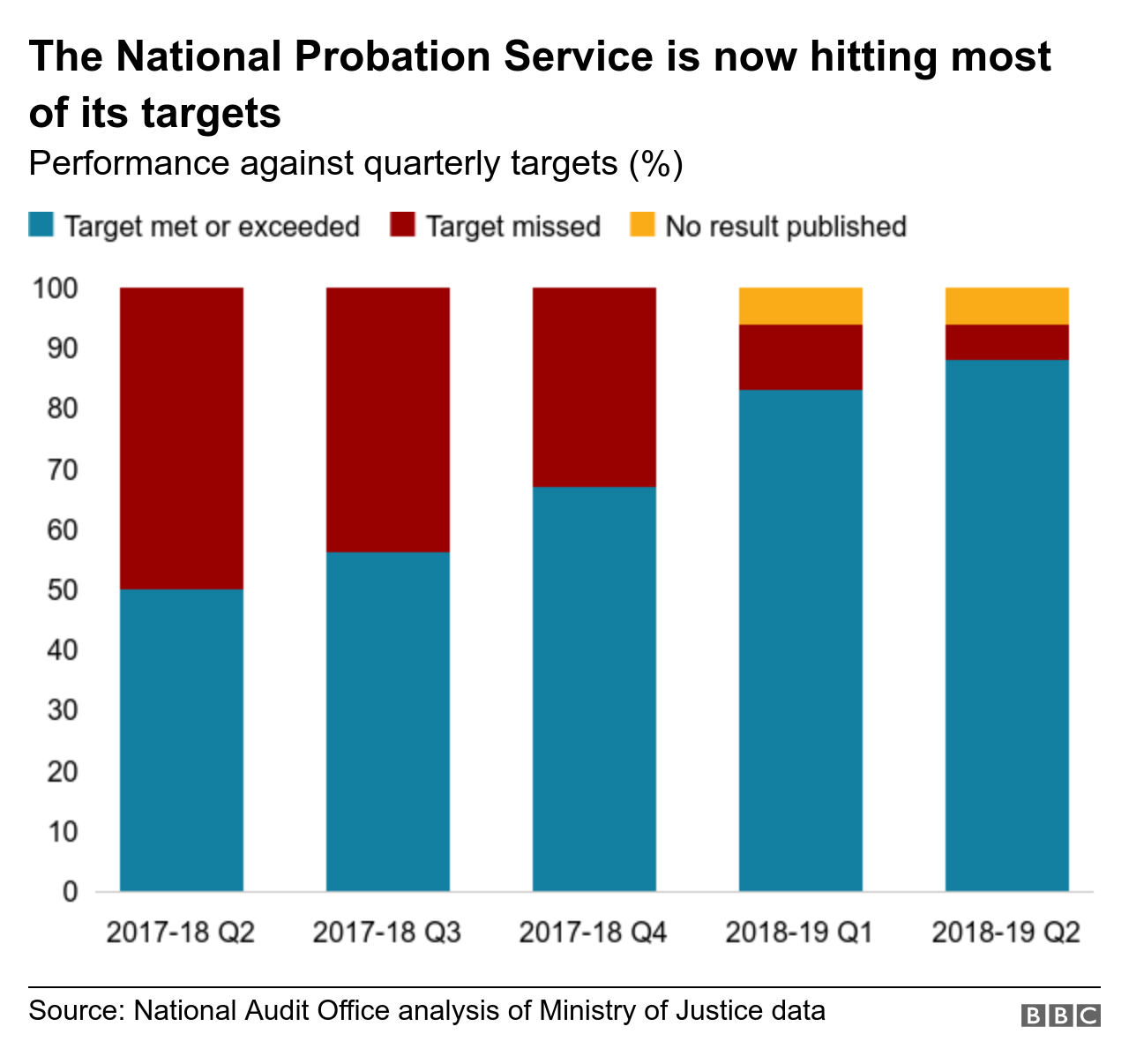

The National Audit Office - Parliament's spending watchdog - also said that the numbers returning to prison for breaching their licence conditions had "skyrocketed" under part-privatisation.

Justice Secretary David Gauke told the BBC he recognised that "the system isn't working" and renationalisation was the best way to reduce reoffending and rehabilitate people.

But he said there was still a role to be played by private companies, as well as charities.

Under the new system, released prisoners and those serving community sentences will be monitored by staff from the National Probation Service based in eleven new regions.

Each area will have a dedicated private or voluntary sector partner, responsible for unpaid work schemes, drug misuse programmes and training courses.

Probation service caused offender, Roger Mann, to fall back into crime: "It doesn't actually do anything for me"

Payment by results - a key element of Mr Grayling's model - will not be used. The community rehabilitation companies' contracts are not being renewed.

When Mr Grayling introduced changes in 2014, opponents warned the public could be put at risk, and many probation staff quit due to fears that the new system would be too fragmented.

The House of Commons justice committee also expressed "considerable concern" at the time, that companies supervising low and medium risk offenders would not be required to have professionally qualified staff - although Mr Grayling promised employees would have the right skills to manage offenders.

'It felt like there was somebody there for you'

The man said he now had to use a call centre to get through to a probation officer (stock image)

A former prisoner with experience of the system before and after Mr Grayling's reforms spoke to BBC Radio 4's Today programme.

"I've now been on probation five, six months and I've seen my probation officer five times. I don't blame the staff because they're just overworked. It's become more about hitting targets, and with that you end up with less time with your probation officer.

"The thing is with me, I've come to a point where I've had enough and I want to do something with my life. And none of that support has come through probation.

"They used to have a work phone number and they used to say, 'if you need to phone me or if there's a problem come up, then you call the probation officers'. They'd ring you back and say, 'is everything alright?', because they'd saved all of our numbers within that phone.

"It felt like there was somebody there for you.

"At the moment, if I want to speak to my probation officer, I have to phone a call centre, who then tries to find my probation officer, so I've gone through two or three people, for basically an email."

Mr Gauke told BBC Radio 4's Today programme: "We've run into difficulties for complex reasons", including that "the case loads have not been what was anticipated", with more higher-risk cases needing to be dealt with and fewer in the lower-risk categories.

He said there was still a "really important role" to be played by both the private and voluntary sectors, for example in terms of drug rehabilitation and unpaid work.

But when it comes to offender management, "it would be better done if that was a unified model and we bring it under one organisation", he told BBC Breakfast. He added that "the reoffending rate has fallen by a couple of points since 2014".

The MoJ said the reforms announced on Thursday were designed to build on the "successful elements" of the existing system, which led to 40,000 additional offenders being supervised every year.

Nail in the coffin for flagship reforms

The decision to renationalise offender supervision will be seen as an admission by the government that Chris Grayling's flagship reforms have failed.

He went ahead in 2014 despite numerous warnings about the considerable risks of splitting probation services between different providers and introducing a method of payment-by-results.

Probation unions and criminal justice experts urged him to at least pilot the new approach, so problems could be identified and rectified. But Mr Grayling went for quick, wholesale change.

He wanted the contracts with the private companies firmly in place before the 2015 general election so the system couldn't be undone if there was a change of government.

However, inspection after inspection signalled serious problems, with the nail in the coffin being Dame Glenys Stacey's report in March.

Probation union Napo welcomed the new approach, saying the part-privatisation should never have happened. It said it would continue to oppose the involvement of private firms in rehabilitation programmes.

And shadow justice secretary Richard Burgon said the Conservatives had been "forced to face reality" that their probation model was "broken".

But speaking on behalf of four companies that are responsible for 17 of 21 community rehabilitation companies in England and Wales, Janine McDowell, of Sodexo Justice Services in the UK & Ireland, said she was disappointed by the decision.

"As well as increasing cost and risk, this more fragmented system will cause confusion as offenders are passed between various organisations for different parts of their sentence," she said.

- Published28 March 2019

- Published1 March 2019

- Published17 April 2019

- Published15 April 2019