Brexit: Is there anything new in Theresa May's 'new deal'?

- Published

Theresa May has urged MPs to back what she has described as a "new" Brexit deal - but what exactly is different in this updated withdrawal agreement?

The prime minister's "new Brexit deal" isn't all that new.

For a start, the withdrawal agreement itself - which includes the backstop plan for the Irish border - remains exactly the same.

That was always going to be the case. The EU has insisted that there will be no further negotiation on the text.

Instead, the government will seek changes to the accompanying political declaration, which focuses on the future relationship after Brexit.

But, as we've said many times before, it is not a legally binding document.

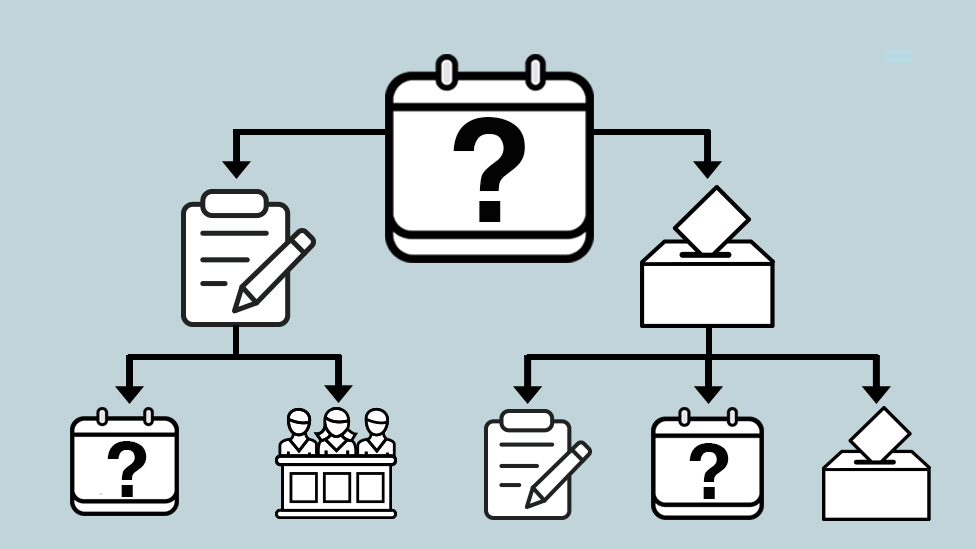

What Mrs May has offered for the first time is the prospect of a vote on holding a second referendum, and a vote on a temporary customs union.

But she says that will only be the case if MPs are willing to approve the withdrawal agreement bill in the House of Commons in the first week of June.

There are also promises on workers' rights and environmental protection - measures designed to appeal to Labour MPs. But similar promises, albeit in different form, have been made before.

As for Northern Ireland, the PM has said that the government would be under a legal obligation "to seek to conclude alternative arrangements" to the backstop by the end of 2020.

But note the word "seek" - it is an aspiration not a guarantee, and finding alternative arrangements, through the use of technology or other means, has so far proved very challenging.

Theresa May says failure to back her deal risks "no Brexit at all"

Mrs May also spoke of a commitment, should the backstop have to come into force, to ensure that Great Britain will stay aligned with Northern Ireland to prevent new checks at the border.

Again, this is something that has been said before.

Nevertheless, the government is portraying this speech as a genuine effort to find compromise.

Others see it as a last roll of the dice.

The trouble is that Brexit has become a binary issue, and almost no-one in politics - whether they voted to leave or remain - seems to want to give up on their vision of how all this should be resolved.

That's why much of the initial reaction to the PM's speech from MPs, from all sides of the House of Commons, including her own backbenches, has ranged from lukewarm to openly hostile.

She will continue to warn that anyone voting against her latest plan risks losing Brexit altogether.

But the biggest problem for Mrs May is that there doesn't appear to be a majority in the Commons for any Brexit option.

That has been clear for many months now.

And nothing in this speech is likely to move the goalposts.

- Published21 May 2019

- Published21 May 2019

- Published13 July 2020

- Published21 May 2019