The violent terms people are searching for online

- Published

"Social media has a substantial role in facilitating gang activity."

That was the claim in the Home Office's serious violence strategy, published in April 2018.

The document says threats of violence, gang recruitment and drug dealing are glamorised and promoted, particularly in videos.

But how serious is the problem?

A social enterprise specialising in countering violent extremism has monitored search engine queries and online video content relating to violence.

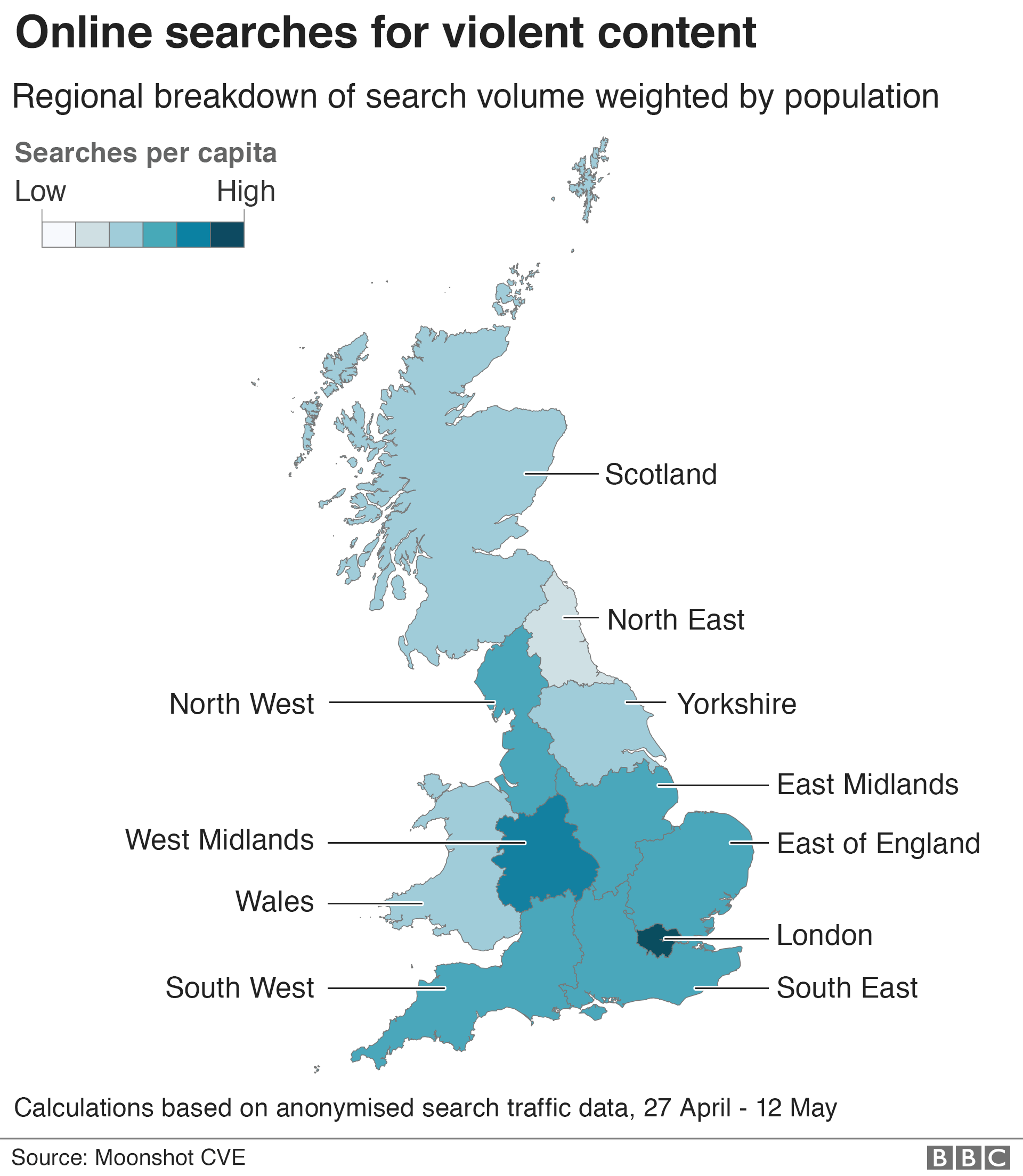

Anonymised search traffic data was gathered from people in England, Scotland and Wales between 27 April and 12 May.

The results provide a fascinating, but disturbing, insight into how the internet and social media may be shaping and fuelling young people's interest in knives, gangs and guns.

Zombie knife

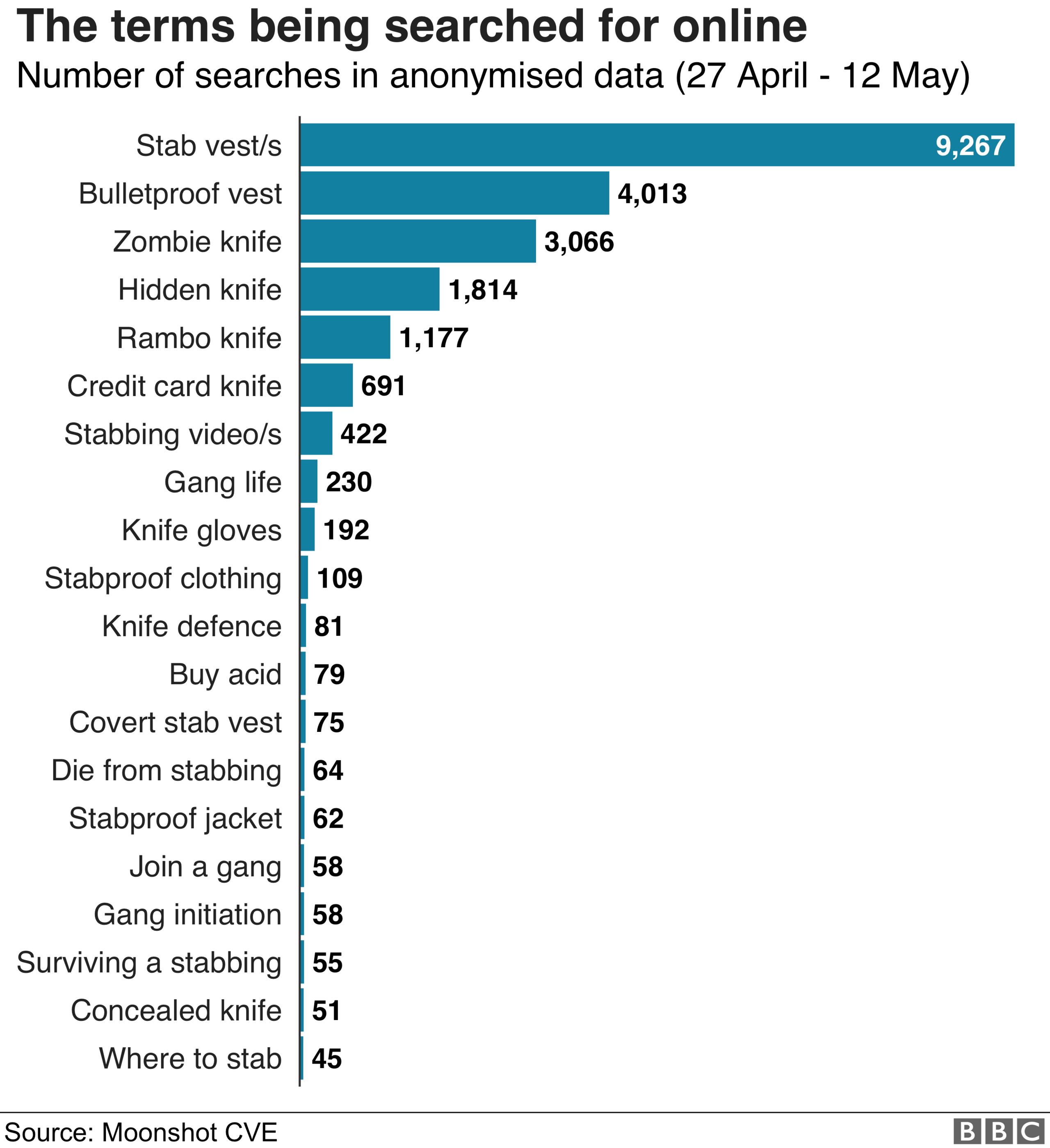

According to the findings, external, there were 22,169 searches indicating "engagement with or vulnerability to serious violence".

Among the most searched-for terms were "stab vest", "bulletproof vest" and "zombie knife", with London and the West Midlands logging the most searches as a proportion of the population.

Researchers placed the searches in different categories.

More than 13,600 were classed as "crisis" with search terms such as "I have been stabbed", "how to survive being stabbed" and "first-aid for stab wound".

Some 7,500 searches were in the grouping, "violent intent". They included "best knife to fight", "where to stab" and "buy machete".

More than 900 concerned "engagement", with people wanting to find out about gangs. A small number, just 110, were in the "diversion" category, which indicated an interest in getting out of gangs.

Analysts explained to me the technique they'd used to collect the data but asked to keep it confidential so as to avoid skewing future surveys and research.

Stabbing victims in 2019

One hundred people have been fatally stabbed in the UK so far this year. The motives and circumstances behind the killings have varied - as have the age and gender of the victims.

Catriona Scholes, who led the project for Moonshot CVE, says although some searches over the 16-day period were likely to be "false positives", with people looking up information for legitimate purposes, the conclusions are invaluable.

"We can use this data to better inform police and civil society when engaging with this issue in their local area," she says.

"We can also use it to produce reactive counter-content that engages with the narratives that are leading people into violence."

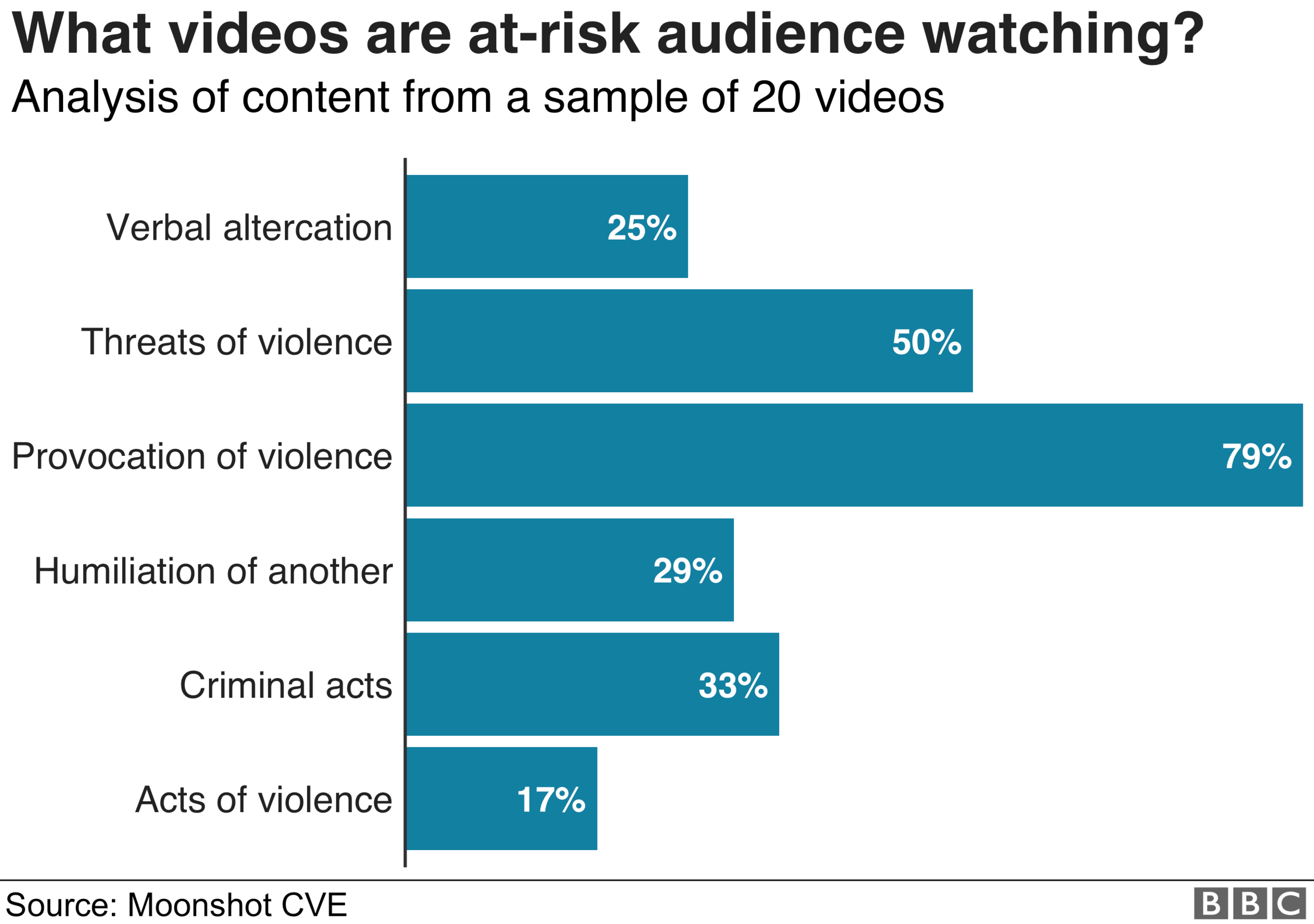

The study also analysed a sample of 20 videos uploaded to YouTube between January 2018 and May 2019 which, analysts say, either "incite or encourage" violence.

The videos received 2.5 million views and 20,500 comments, likes or shares.

More than three-quarters of the films depicted people being provoked into violence. Half showed threats of violence with a named target and in a third there were "criminal acts".

According to the research, the vast majority of those watching the videos were male, with two-thirds under 25.

"We found that the people who post this footage typically post the original live video on Snapchat and Instagram before later re-uploading it to YouTube, thereby maximising the lifespan and reach of their content," says Scholes, a former Metropolitan Police officer.

"It demonstrates clear intent not merely to share a post with friends, but to encourage a culture of violence among as many people as possible," she adds.

Moonshot says the findings should spark a nationwide campaign with targeted messaging and online advertising services to provide search engines with alternative, credible content to challenge "harmful" narratives.

It's also calling for off-line help to be made available for those who may be at risk, bringing "social work into the online space".

The research is well-timed.

The government is half-way through a consultation period on proposals for what it hopes will be a "world-leading package of online safety measures", one of which involves ensuring users exposed to violent material are directed to support.

There are also plans for a statutory duty of care to make technology companies and social media providers take more responsibility for online safety, with the measures enforced by an independent regulator.

It'll be months, probably a year or two, before such a system is in place.

The results of this study suggest it can't come soon enough.

- Published18 July 2019

- Published17 May 2019