Trans conversion therapy survivor: 'I wanted to be cured so asked to be electrocuted'

- Published

Carolyn Mercer had gender reassignment surgery after decades of feeling uncomfortable in a man's body

On a dull autumn day in 1964, two NHS doctors strapped a 17-year-old boy into a wooden chair in a dark, windowless room and covered him in electrodes. During hours of so-called therapy, they repeatedly electrocuted him while showing him images of women's clothing.

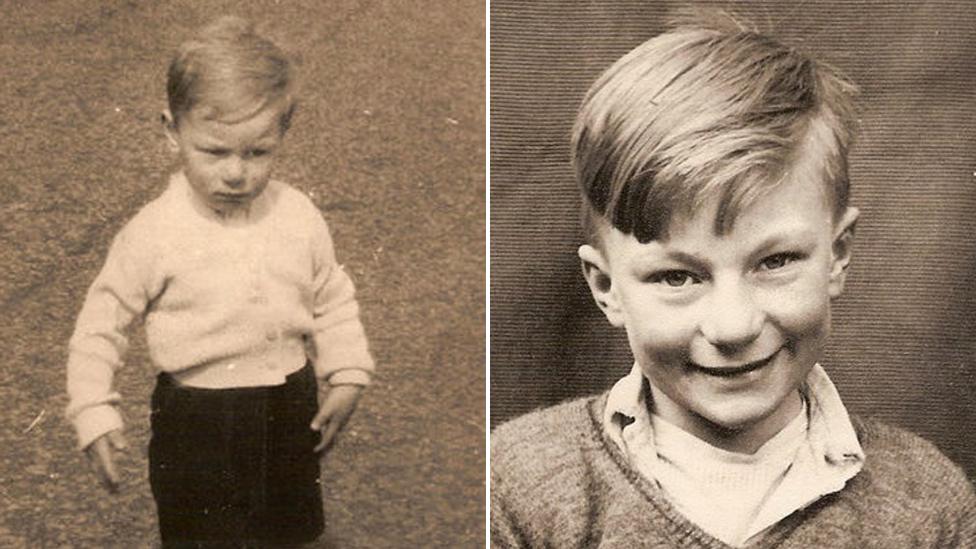

In a coffee shop in Soho, Carolyn Mercer, now 72, smiles as she looks at a photograph of the boy. "That person has grown and developed," she said.

"But it's still me."

Carolyn - who prefers not to mention the male name she used to go by - remembers the first time she realised she was different. As a three-year-old boy playing in the backstreets of Preston, Lancashire, she persuaded her younger sister to switch clothes with her. The pair swapped their pre-school uniforms and Carolyn stood on the front step of her mother's shop, hoping people would see a little girl standing there.

"It was never about clothes... It was about something deep inside," Carolyn said. "I was a boy, and I didn't want to be."

Carolyn Mercer (left) growing up in the 1950s, with her younger sister

When Carolyn was born in 1947, society's attitude to gay and transgender people was far from accepting. England and Wales was still 20 years from legalising homosexual relationships - or using the word "transgender".

As a little Lancashire lad in his sister's school skirt, Carolyn had no words to describe her feelings. But she now knows she was a trans girl with gender dysphoria, external - distressed because her biological sex did not match her gender identity.

"I went to sleep hoping someone would invent a brain transplant to put my brain in a more appropriate body," she said.

Throughout boyhood, Carolyn's secret desire to live as a woman morphed into an all-consuming self-loathing.

"I knew what I wanted to be, and that dissonance and dysphoria [was] accentuated from the age of three onwards," Carolyn says

"That self-hatred was because I wanted something so absurd."

Carolyn said she felt "dirty" because society viewed transgender people as "wrong" and "evil". "If it was wrong and it was evil, that must be because I am wrong, and I am evil," she mused.

As Carolyn grew into a strongly-built teenager, she threw herself into trying to be "good bloke" - playing "masculine" sports like rugby and boxing. But she could not shake the deeply uncomfortable feeling of pretending to be someone she was not.

Carolyn began to feel depressed and suicidal. She thought it "would be easier" for her friends and family if she died than if she told anybody how she felt.

Then, aged 17, she shared her secret with a local vicar. He took her to see a doctor at a psychiatric hospital. "Five or six" sessions of aversion therapy at a hospital in Blackburn were arranged.

"I asked for that, I wanted to be cured," Carolyn said.

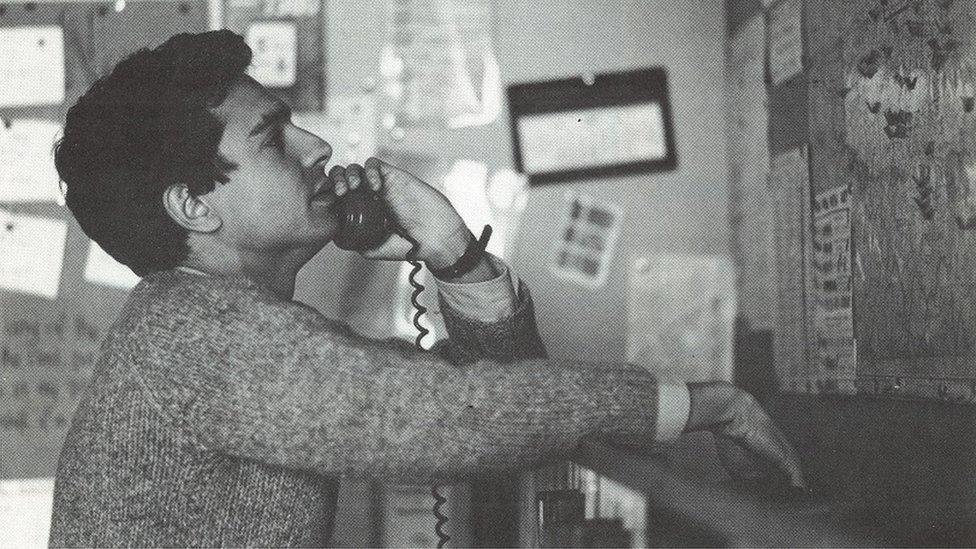

Electric shock therapies of various kinds have been used in medicine since the 1930s (file image)

Carolyn was strapped to a wooden chair in a dark room as doctors dipped electrodes in brine and attached them to her arm. They projected image after image of women's clothing on to the wall in front of her.

As each photograph snapped into view, a current was passed through the electrodes to give her a painful electric shock. Carolyn vividly remembers the surging shock wrenching her hand painfully upwards as her arm remained pinned to the chair.

Despite her tears of agony, the doctors pressed on. They were convinced that if she "learned" to associate thoughts about her gender with memories of pain, she would stop thinking she was a woman.

After a few months of treatment, Carolyn opted out of more. But the trauma was so great, she went on to experience physical shaking and flashbacks for the next 40 years.

What is conversion therapy?

In 2017 there were widespread protests in Sao Paulo, Brazil, after a judge overruled an old law forbidding "cure" therapy for LGBT+ people

So-called "gay-cure" conversion therapies claim to help change someone's sexuality or gender identity. Methods include hypnosis, exorcisms and aversion treatments such as patients receiving electric shocks or vomit-inducing drugs.

The therapies were available on the NHS until the 1970s. Both the NHS and the government said there was no record of how many people were treated or died as a result of the treatment.

Various forms of conversion therapy continue to be carried out across the world on LGBT people despite scientific evidence it is harmful and ineffective.

In 2018, a survey suggested 2% of the LGBT community in the UK had undergone conversion therapy - prompting the government to promise it would ban the treatment.

Work is under way to see how a ban would be implemented. But the complex and deeply entrenched beliefs that fostered the spread of the therapy mean it will still be some time before it is brought to an end.

For a while, Carolyn thought the therapy had worked.

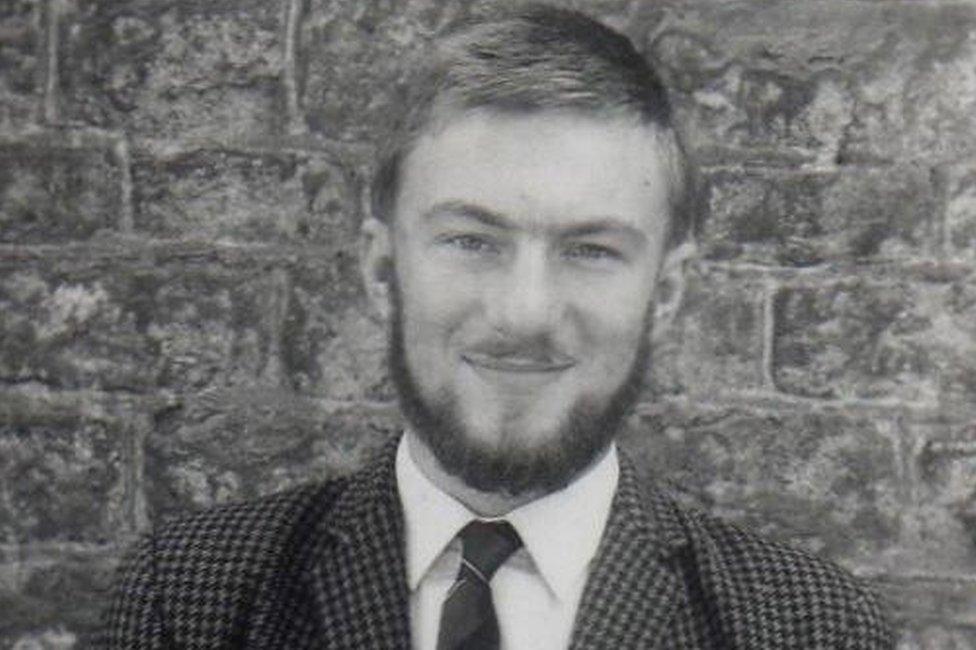

She led as "manly" a life as possible. By the age of 19, she had a wife and a baby daughter. She became a maths teacher and was promoted quickly, soon becoming one of the youngest head teachers in Lancashire. But her dysphoria had not been stifled.

A 19-year-old Carolyn on her first day of teaching college, two years after having aversion therapy

Her depression worsened as she was gripped by uncontrollable shaking whenever she thought about the treatment she had received.

"Did [the therapy] work in that it affected my body? Yes," Carolyn said. "Did it work in affecting my mind? Only in terms of making me hate myself even more."

After years of struggling to cope with the all-consuming dysphoria, Carolyn eventually began taking hormones to develop breasts in the early 1990s.

This was the beginning of a process described by many in the transgender community as "transition" or, as Carolyn prefers, to "align my gender expression with my gender identity". It's "a bit of a mouthful", she says, "but it suits me".

Although her family had been "incredible", they did not actively support her decision. "They actually liked the person they saw - a different person to the one that I was looking at," she said.

Double mastectomy

At work, Carolyn bound her developing breasts to hide the effects of her treatment. But in 1994, a journalist learned she was taking hormones, and Carolyn's personal life was plastered across tabloids claiming it was in the "public interest" to report the secret of a high-profile head teacher.

The episode forced Carolyn to rethink taking hormones. The following summer, she had her breasts surgically removed - an operation normally reserved for cancer patients.

Once again, an impassable void had lodged itself between who Carolyn was, and who she wanted to be. But after several more difficult years - though with the support of her staff, students, friends and family - Carolyn, aged 55, retired early to finally undergo the surgery she had been dreaming of for decades.

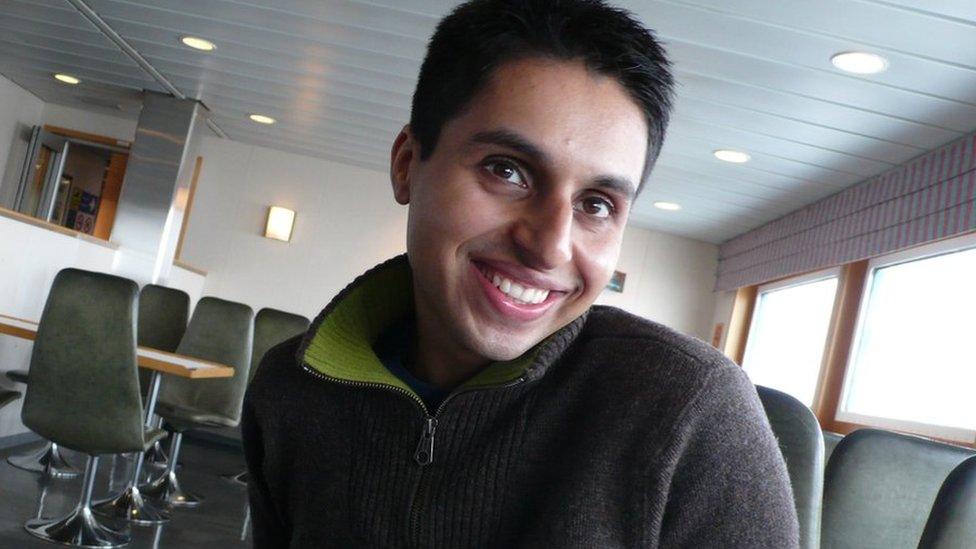

Carolyn's road trip in the US at the age of 67 was the first holiday she had been on where she felt she could enjoy herself

"Life is so, so much better. I don't have that dark secret hidden away all of the time."

Some members of the trans community say the person they were before surgery is dead. But for Carolyn, who has lived most of her life as that person, the little boy wearing his sister's pre-school uniform is very much alive.

"I'm still the same person with the same experiences," she said.

She continues to struggle with being happy. Following conversion therapy, she became so used to burying her innermost desires that she finds it difficult to let herself be happy.

"You show me a menu in a restaurant and you say 'which would you prefer?', I don't know," she said.

"Some will find it sad, but it's something I've come to terms with... I don't have a light anymore, or emotion like that, because I suppressed it for so long."

If you are struggling with gender dysphoria, these organisations may be able to help.

- Published30 July 2019

- Published3 April 2019

- Published4 April 2019

- Published3 July 2018

- Published30 April 2019

- Published4 March 2019