How do you stop people dying from illegal drug taking?

- Published

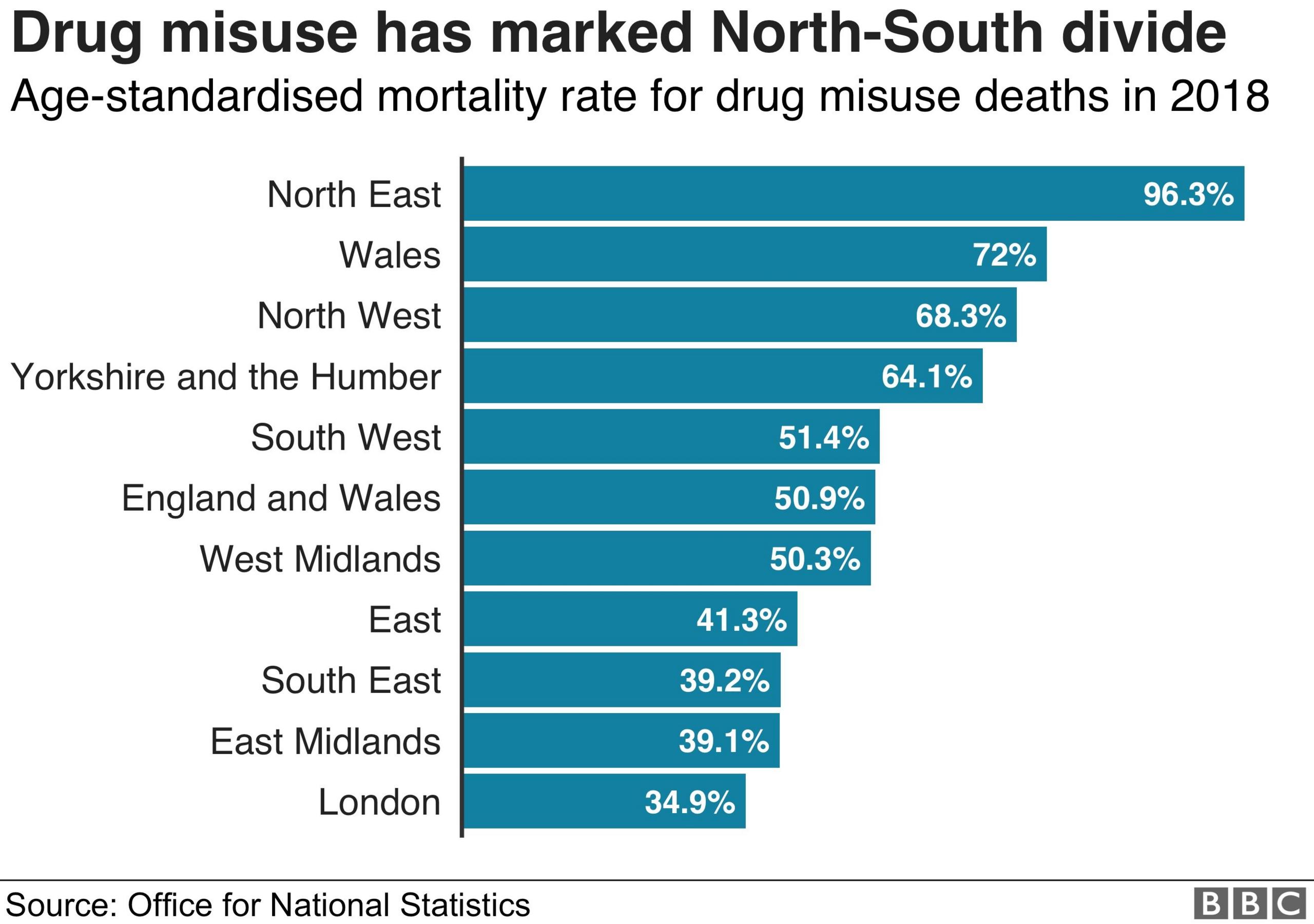

The ONS has referred to a "marked north-south divide" in the rate of deaths as a result of drug misuse

There is real frustration among frontline drug workers, experts and academics at the record numbers of people dying from illegal drugs in England and Wales.

The blame game has begun with fingers pointed at government cuts and at a failure to implement evidence-based measures that would reduce deaths.

But others say responsibility lies with many of the drug users themselves.

The Home Office notes that half of illicit drugs deaths are among users who have either never taken part in treatment or have not done so for many years.

Ministers like to emphasise the part played in the death figures by an ageing cohort of heroin users - people who started using heroin in the 1990s and 2000s, when its use spread across the country.

Now in their 50s, 60s and 70s, their bodies are giving up on them.

But others say the government is culpable for not doing more to protect vulnerable people from the harms of illegal drugs.

The purity of heroin and crack is increasing, its price is falling and suppliers are becoming more sophisticated at getting their product to customers in every part of the country.

The spate of urban knife killings, drive-by shootings and the county lines supply networks all bear the fingerprints of increasingly muscular organised criminal groups. If there is a "war on drugs", the bad guys are winning.

At the same time, critics argue, the government has presided over big cuts to drug treatment services - spending is down 27% since 2015 with some of the biggest cuts in places with the worst problems: Blackpool, Hartlepool and North Tyneside.

The ONS refers to a "marked north-south divide", external in the rate of drug misuse deaths.

In the north east the rate has doubled in a decade, now at 96.3 deaths per million people.

In London last year it was 34.9 deaths per million.

In 2016 the statutory body set up to offer expert advice to the Home Office, the Advisory Council for the Misuse of Drugs, recommended a number of measures to cut the number of drug deaths.

Its report called on ministers "to protect the current levels of investment in evidence-based drug treatment" and to supply heroin addicts with substitute treatment or, more controversially, heroin itself.

The experts also urged the Home Office to allow medically-supervised drug consumption clinics in localities with a high concentration of injecting drug use.

State-funded heroin

The politics of drugs have meant that ministers have shown reluctance to follow their experts' advice for fear of sending the wrong message on drugs.

Giving state-funded heroin to those addicted to opiates, or allowing users to inject themselves with street-bought heroin in state-sanctioned consumption rooms is seen as a step too far, whatever the evidence says about the lives they might save.

The Home Office has commissioned an independent review of drugs policy, the first part of which will consider "evidence-based approaches to preventing and reducing drug use".

But the review, headed by Dame Carol Black and due to report back this summer, will not consider "changes to the existing legislative framework or government machinery".

In other words, the debate about decriminalisation or legalisation of drugs will not be heard.

And that, according to campaigners, is a massive gap in its remit because it prevents consideration of many evidence-based approaches which could, it is argued, save countless lives.

- Published15 August 2019

- Published15 August 2019

- Published15 August 2019